Why exporting isn't just about shipping

- Published

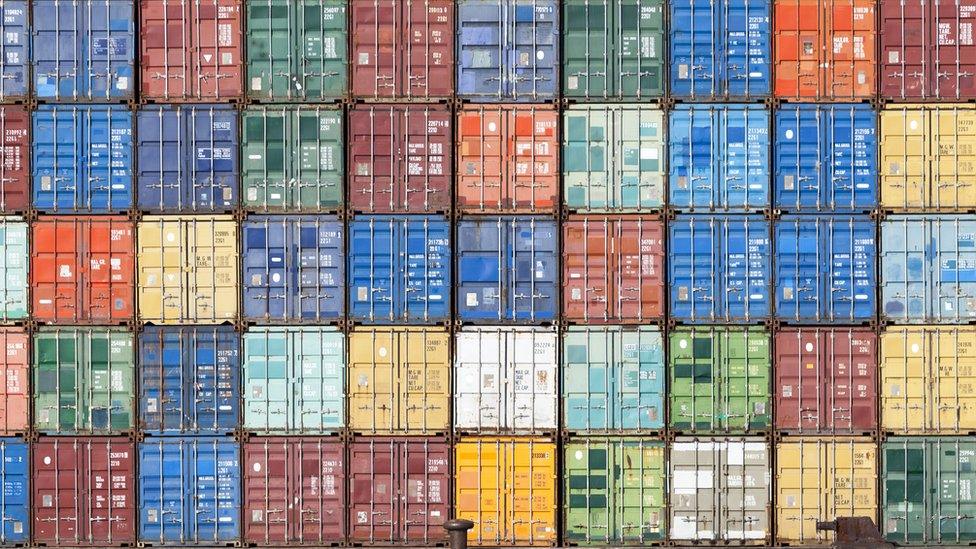

You can't put a service on a container ship and send it around the world the way you can with physical goods

The future of international trade has leapt up the agenda.

The British vote to leave the European Union is one central reason. There is also the election of Donald Trump after a campaign in which he was highly critical of some US trade agreements.

Much of the debate has focused on trade in goods. Will there be tariffs on British exports to the EU and vice versa? President Trump has threatened carmakers with a "border tax" if they expand operations in Mexico.

But what about services? After all, the service sector dominates most economies, external.

It accounts for 78% or more of national economic activity in the UK, France and the US. Those are well known as service-driven economies. But in Germany, that great manufacturing powerhouse, it's getting on for 70% and even in China it is close to half.

People often travel abroad for cheaper health treatment such as dentistry

When we look at cross-border trade, however, it is a rather different story. The value of global trade in goods still exceeds services, external by a factor of more than three.

But services trade is growing and it is important for many economies.

Barriers to services trade have proved to be harder to deal with.

They come in the form of regulation - not the tariffs or taxes that impinge on commerce in goods.

Countries sometimes impose limits on the percentage share of ownership that foreign companies can have in a business that provides services. In China, external, for example, the limit is 50% for insurance and some telecommunications services.

There can also be nationality requirements. In China again, the chief partner in auditing and accounting firms must be a Chinese national.

In just about all countries practitioners of many professions require approved qualifications (often for very good reasons). The extent to which there is mutual recognition of other countries' qualifications varies.

There are also sometimes licensing and residency requirements which can stand in the way of cross-border provision.

China may be known for its manufacturing capabilities, but services now account for half of its economy

It is also the case that the nature of many services does make trade intrinsically rather more challenging. You can't put a service on a container ship and send it around the world the way you can with goods.

But it is possible to trade services internationally. A stockbroker in London can buy and sell shares for German investors. People can travel abroad for health treatment. Firms can establish a commercial presence in other countries. And individual practitioners can go abroad and work as an independent supplier - perhaps as a plumber - or as an employee of, for example, an insurance company.

So liberalising services trade is more complicated than it is for goods.

But there have been efforts.

The World Trade Organization's rulebook includes something called the General Agreement on Trade in Services, or GATS., external

WTO member countries have made commitments during past negotiations about the extent to which they allow foreign suppliers access to their services markets. These vary from country to country and are listed in "schedules" attached to the agreement.

The GATS also has rules that promote transparency, to make it easier for businesses to navigate any rules that affect them. There are also rules that prohibit discrimination between different trade partners.

Governments in many of the big service-driven economies - Europe and the US in particular - have seen the GATS as a useful start, but as very much unfinished business.

Attempts to regulate how services are traded are continuing

So there is also a separate negotiation under way called the Trade in Services Agreement (TiSA), external. It is not yet complete and so it is not yet an "agreement", strictly speaking.

The negotiations involve 23 WTO members. That counts the European Union as one, so it will probably rise to 24 when the UK leaves the EU.

TiSA does not have a high profile in news terms, but has been very controversial.

Critics, external accuse the governments involved of negotiating in secret. They also criticise the "ratchet clause" that the agreement is likely to include, which would prevent countries from reintroducing trade barriers that they had removed.

Critics say that would make it harder for any government involved to reverse the privatisation of any services that had been transferred to the private sector. They also say it would undermine the rights of governments to regulate in the public interest.

The European Commission - which negotiates on trade policy for the EU - rejects this.

"Quite to the contrary, the right to regulate services will be enshrined in TiSA. Rather, the objective is to tackle discrimination that currently prevents service suppliers from operating in another TiSA party," a spokesperson says.

On the ratchet clause the Commission says, external it won't have the effect that critics allege. And it says the EU won't make commitments on allowing foreign suppliers to provide some key publicly funded services, including health and education.

Financial services exports such as share trading will be an important factor in Brexit negotiations

Service industries are also likely to be an important area for British trade negotiators looking at opportunities for UK business after leaving the European Union.

Financial and business services account for about half the total of British services exports, which is in the region of a quarter of a trillion pounds ($300bn). It will be an important factor for UK commercial relations with the EU, and for any new agreements that might be done with countries outside the EU, including the US.

The UK still exports more goods than services, but that lead has narrowed dramatically. Research commissioned by Barclays Bank, external projected that services could account for more than half of British exports within a decade.

So barriers to cross-border trade in services really will matter to the British and many other economies.