Q&A: The Tory plan to cap energy prices

- Published

The Conservatives have released more details about their proposed cap on energy prices.

They say that 17 million people will benefit - by saving £100 a year on their bills.

But many in the industry think it is a bad idea, as it will reduce competition in what is supposed to be a free market.

And while the majority of householders may benefit, at least in the short term, millions of people who are currently on cheaper deals could end up paying more.

So, if the Tories win the election, how would their plan work?

Why are the Tories proposing to cap energy bills?

Even though there was pressure on suppliers not to raise bills, five of the big six have gone ahead with some large price increases this year.

Among the more eye-catching increases, EDF will raise electricity prices by more than 18%, and Npower put up electricity prices by 15% in March.

While the suppliers blamed an increase in wholesale and environmental costs, the regulator, Ofgem, said such sharp hikes were not justified.

How would a cap work?

The cap would be an upper limit on what suppliers could charge. It would follow the model introduced for the 16% of households that use pre-payment meters.

Since April, these customers have had their bills capped, according to where they live in the country.

Ofgem would probably base the precise level of the cap on the cheapest standard variable tariffs in each part of the UK, taking into account a range of additional factors, including the variable costs for transporting energy there.

In other words, the cap would vary in different parts of the country and be re-set every six months.

Who would be affected by a cap?

About 17 million households would be affected. They consist of customers who are on standard variable tariffs, which are typically much more expensive than fixed-rate deals.

Ofgem and consumer groups have repeatedly tried to persuade more people to switch to the cheaper deals, but with limited success. As a result, 66% of consumers remain on standard variable tariffs.

The remaining 8.5 million customers who have switched to cheaper deals would not be affected by the cap immediately. However, if the industry has its profitability constrained by a cap on variable tariffs, it is likely that the very cheapest deals would disappear.

Could consumers still save money by switching?

Yes. There will still be cheaper deals on offer, but the concern is that the savings - compared with the most expensive tariffs - will be smaller than they are now.

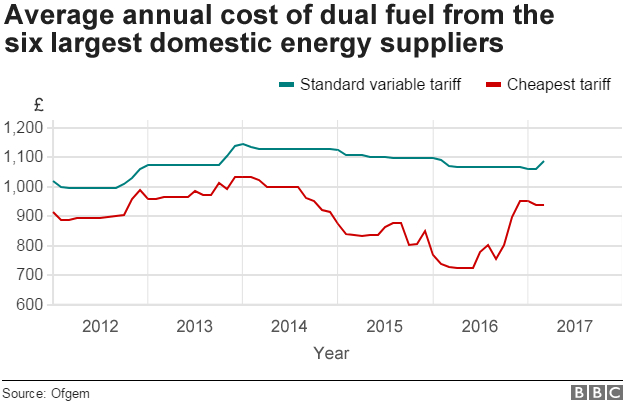

As the chart above clearly shows, there is some evidence that this is already happening. Since the middle of last year, the gap between the cheapest tariffs and the most expensive have been narrowing. SSE, for example, has raised its cheapest dual fuel deal by 37% since October last year, according to the comparison site Uswitch.

However, consumer groups believe fewer people would switch supplier if there was cap - as there might be less incentive to do so.

So will energy prices rise, as suppliers claim?

Prices are likely to rise for some, especially those on fixed-rate deals. For the majority, prices will be capped. But should wholesale costs rise, it's worth remembering that Ofgem will raise the level of the cap, so it is possible that all prices will rise anyway.

Equally well, the level of the cap could fall, cutting bills for those on svts.

The truth is that suppliers will try to adjust prices to maintain their profit margins. According to Lazarus Research, the profit margins of five of the big six suppliers rose to 5.6% last year - the largest since 2009.

How do Labour's plans compare?

In February, shadow chancellor John McDonnell promised that Labour would also introduce a cap on energy charges.

However at this stage, we do not know how this would work. In the 2015 election, the Labour leader, Ed Miliband, promised to freeze prices for a 20-month period.

- Published9 May 2017

- Published9 May 2017