Reality Check: Why does Labour want to control National Grid?

- Published

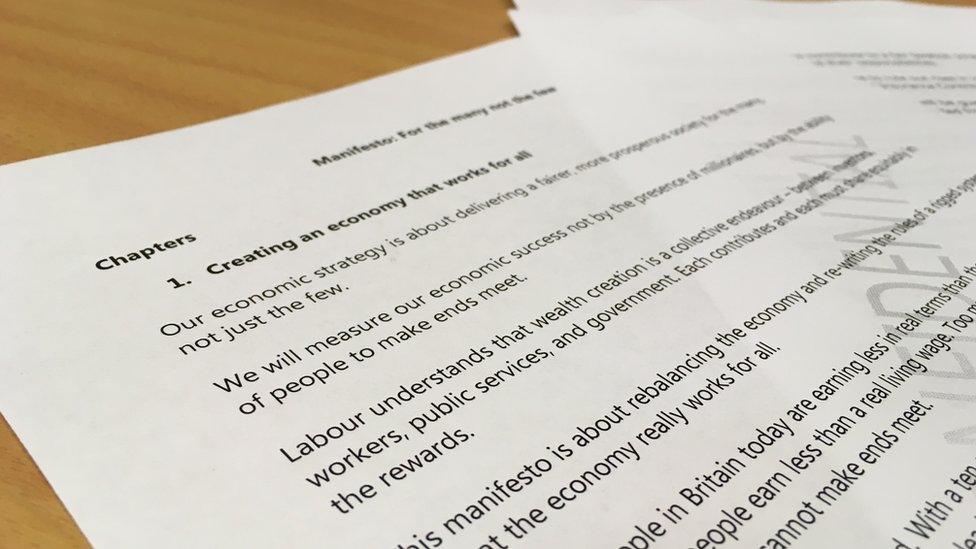

The leaked version of the Labour Party manifesto commits to "take energy back into public ownership to deliver renewable energy, affordability for consumers, and democratic control".

Part of that would involve "central government control of the natural monopolies of the transmission and distribution grids".

Natural monopolies are businesses where there are no benefits to be had from competition.

They are usually areas where there is a lot of initial spending on infrastructure needed, such as train tracks or water pipes.

It does not mean there can only be one business serving the whole country, but it makes no sense to have companies competing to provide such services to consumers in a particular area.

It would be inefficient, for example, to have two taps in your sink offering water from different providers or two sockets in your wall with electricity from competing energy companies.

Being a natural monopoly gives businesses enormous market power, which means that they must be regulated.

Whether it is better to have such services provided by government or by private companies regulated by government is a matter of political opinion.

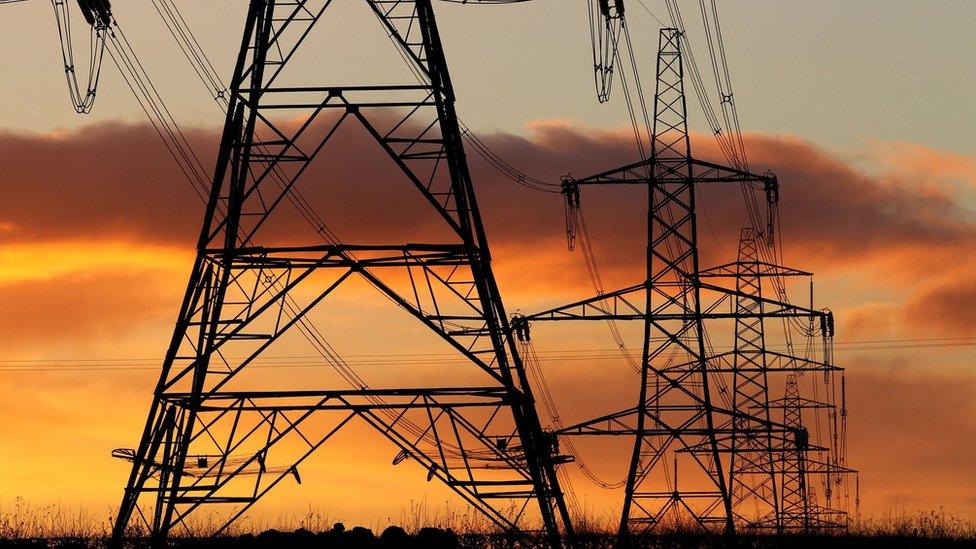

National Grid's main business is moving electricity and gas round the country. This is known as transmission. The very last leg of the journey into people's homes and businesses - known as distribution - is done by a number of different companies. National Grid does own a stake in Cadent Gas, a distribution firm, but most gas distribution and all electricity distribution is controlled by other firms.

The cost of transporting gas and electricity round the country accounts for 29% of the average dual-fuel (both gas and electricity) bill, according to Energy UK, external, up from 23% in 2010. But National Grid says its share of that - the transmission cost - is only 5% of the typical electricity bill, and 3% of a gas bill. The rest is distribution costs.

Owning the transmission and distribution network would give the government considerably more control as it attempted to deliver promises in the leaked manifesto to deliver renewable energy and affordability for consumers, including keeping the average dual fuel bill below £1,000 a year.

The leaked manifesto also pledges to ban fracking (the use of high pressure liquids to extract gas from rocks) and use carbon capture (stopping carbon dioxide from escaping with other waste gases) as it moves to cleaner fuels.

Control over the network might help with this, but the government via its regulator and planning decisions already has a big say over the future energy mix.

Just nationalising National Grid (which is worth about £38bn on the stock market at the moment) would not achieve what Labour is promising - it would give the government the company that owns the UK's electricity and gas transmission (it might also leave the government owning National Grid's energy business in the US).

The distribution part of the equation is a slew of other companies - for gas alone it would be SGN, Northern Gas Networks, Wales and West Utilities, as well as Cadent Gas.

But the leaked manifesto, external calls for control of these companies, which could possibly be achieved by buying stakes in these businesses rather than nationalising them.

BBC business editor Simon Jack says National Grid's UK business is estimated to be worth about £25bn.

"A chunky purchase but one that could quite easily financed in that it makes enough money to repay the interest on any money borrowed to buy it."

National Grid has a lot of shareholders.

It's been listed on the London Stock Exchange since 1995.

Its shareholders, including 880,000 small shareholders, would be very upset if they didn't get a good price from the government for their shares.

There are not many precedents for nationalisation of profitable companies in the UK - companies are usually nationalised when they are in financial difficulties - so it is not clear at this stage what the process would be.

- Published11 May 2017

- Published11 May 2017

- Published11 May 2017

- Published10 May 2017

- Published10 May 2017