China’s debt mountain: Should we worry?

- Published

- comments

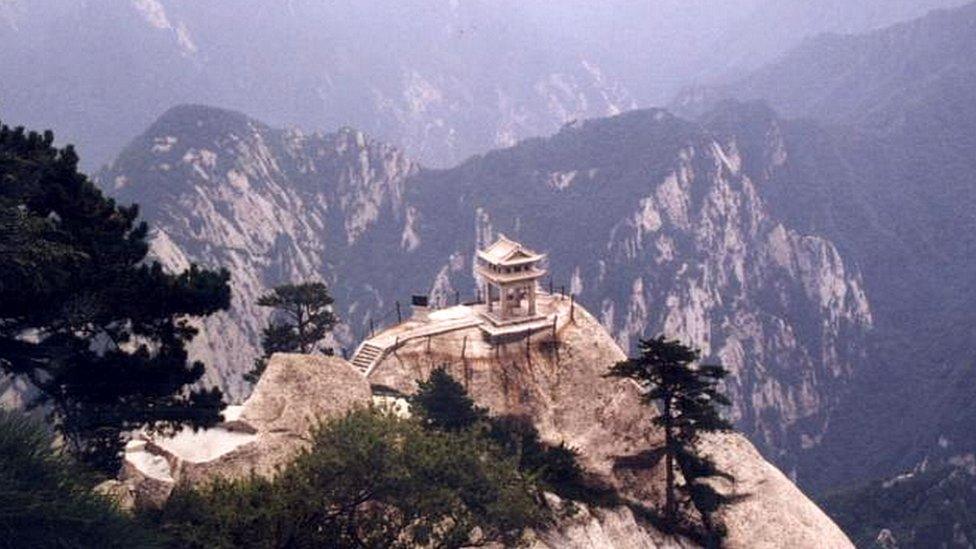

Not all China's mountains are as scenic

In his new book Grave New World, Stephen King says: "For better or worse, China is simply too big to be ignored."

Mr King is not the rather better-known writer of horror novels (though his robust opinions on the dangers of monetary largesse can tend towards sleepless nights).

This Mr King is senior economic adviser at HSBC. And a China expert.

Writing about the country's economic slowdown in 2012, he said: "China's debt fuelled expansion was never likely to be sustainable."

The amber warning lights came back on this morning when the ratings agency Moody's downgraded China's credit rating, its investor benchmark for analysing the country's economic performance.

Now, the rating is still A1 - the agency's fifth highest - but nevertheless does highlight growing concerns about the amount of debt the world's most populous country is carrying.

The problem is not the government's direct debt, which at less than 40% of GDP is modest by Western standards, or the eminently manageable 3% deficit (the rate at which that debt is rising).

The issue is the debt being carried by the country's companies, or more specifically the "state-owned enterprises" (SOEs) that constitute the grumbling and sometimes out-of-date engines of the Chinese economy.

And the debts being carried by the country's local governments - which, of course, in a state the size of China, are a little more significant than those of an English town council, say.

Local difficulties

Here, the picture is different.

SOE debt stands at 115% of GDP, a figure that is steadily rising and is far higher than, say, comparable figures for Japan and South Korea (where comparable debts are around 30%).

Moody's estimates that bringing the leverage of those firms down to more manageable levels would cost more than $400bn (£308bn).

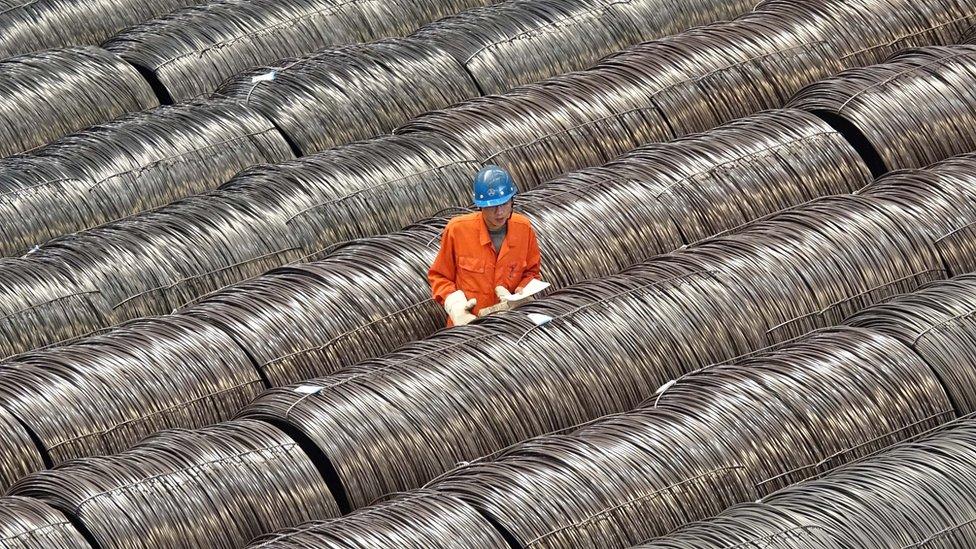

At the same time, China's own finance ministry has warned that some local authorities are struggling to meet day-to-day operating costs, as they find themselves caught between supporting often inefficient local businesses - making steel, for example - or funding the unpaid debts and unemployment costs associated with shutting down or reforming the mainstays of regional economies.

Chinese steelmaking is often inefficient

Now, China certainly has deep pockets.

Its foreign currency reserves stand at more than $3tn and its annual current account surplus is $200bn.

So, debt sustainability is not a near and present danger.

But, if the old joke is that when America sneezes, the rest of the world catches a cold, when it comes to China, it only has to think about reaching for its handkerchief and the global economy can suffer a fit of the vapours.

When China announced weaker-than-expected economic data at the beginning of 2016, world stock markets went into free fall and commodity prices tumbled.

Straw in the wind

In 2010, average Chinese growth hovered around 10%. It is now between 6% and 7%.

More manageable than the heady days of seven years ago, yes, but there are fears that a lack of economic reform could see growth fall to 5% as President Xi Jinping balances the drive for a more efficient economy (with all the dislocating restructuring costs and possible job losses that could incur) with the need to keep political tension to a minimum.

In a jittery world, China's debt mountain can loom larger than the fundamentals suggest.

And Moody's downgrade is just one straw in the wind.

Asian stock markets hardly paused for breath when it was announced earlier this morning and warnings of a "hard landing" for the Chinese economy have been oft-predicted and not materialised.

But, Chinese bond yields are rising as investors demand a higher risk premium for funding the government's liabilities.

There is no need to rush for the lifeboats yet.

However, it's probably worth knowing where they are.

- Published8 May 2017

- Published1 May 2017

- Published3 March 2017