Are manifestos worth the paper they are written on?

- Published

- comments

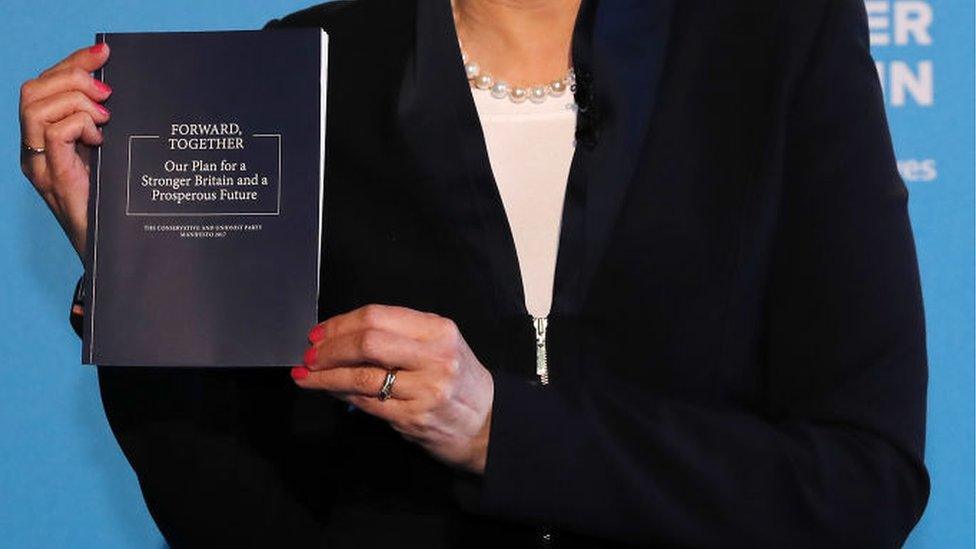

The Tories have been deliberately vague on costings, the IFS says

As Carl Emmerson came to the end of his presentation on the Tory and Labour manifestos presented to the voters, there was an "ouch" moment.

"The shame of the two big parties' manifestos is that neither sets out an honest set of choices," the deputy director of the Institute for Fiscal Studies said.

Does that mean there is no point in reading them?

Not quite.

The importance of the manifestos is that, economically, they propose quite different approaches to the next five years.

The Conservatives say they will maintain tight controls on public spending and that any new Tory government will seek to "balance the books" by 2025 - meaning the government would spend as much as it receives in tax receipts.

The party has been deliberately vague on costings ("extremely light" as the IFS describes it), not wanting to tie the hands of any new prime minister or chancellor.

The voters are being asked to take the manifesto on trust.

In sharp contrast, Labour proposes making the economy operate more "fairly" with higher levels of tax on the wealthy, higher levels of public spending and more borrowing to pay for capital investment projects.

The IFS says Labour's plans would make people "worse off"

Its costings are detailed and open to interpretation.

The IFS lays out major challenges for both parties.

It says the Conservative proposals would mean cuts in benefit payments and lower spending per pupil in education, for example.

Is that deliverable in an era of generally falling incomes for the "just about managing" and a need to improve schools?

When it comes to the NHS, the IFS says that the period after the election would be "incredibly challenging".

The institute also points out that continuing the 1% public sector pay cap would take pay levels in the public sector to their lowest level relative to the private sector in "recent decades".

And suggests that after 8 June - if they win - the Tories could announce spending plans less stringent than envisaged, as the David Cameron-led government did in 2015.

The new government could even raise some additional taxes.

When it comes to Labour, the IFS says that plans to raise £49bn in extra taxes from those earning over £80,000 and higher levels of business taxes are an "overestimate" and would make people "worse off".

The Tories have little to say on the possible economic impact of a rapid cut in immigration, the think-tank says.

It says that even on optimistic forecasts, the tax increases would raise £40bn a year in the short term and less in the long term.

That would be a £9bn annual shortfall.

The taxes are also not "victim-free", as the IFS describes it.

"When businesses pay tax, they are handing over money that would otherwise have ended up with people, and not only rich ones," Mr Emmerson said.

"Millions with pension funds are effectively shareholders [in businesses]."

The IFS accepts that Labour does not propose to raise spending to "unusually high" levels compared to other advanced Western economies such as Canada.

And that increased investment spending could have "positive long-term economic returns".

Telling fibs?

So why does the IFS say that the manifestos are less than honest?

Firstly, because it is not convinced that the Conservatives can deliver the cuts the manifesto suggests and maintain public services.

Nor is it convinced that Labour will be able to raise the amount of revenue it expects and that the extra taxes would not damage the broader economy.

But there are also two more substantial challenges.

Labour has little to say on tackling the increasing costs of our ageing population, the IFS says.

And the Tories have little to say on the possible economic impact of a rapid cut in immigration, which the government's official economic watchdog, the Office for Budget Responsibility, suggests could reduce tax receipts by £6bn a year.

The two parties are laying out two very different approaches to the economy.

At that high level, the manifestos are important.

Even if, when it comes to the detail, voters might need to reach for a pretty hefty pinch of salt.