How one man built a global hospitality empire

- Published

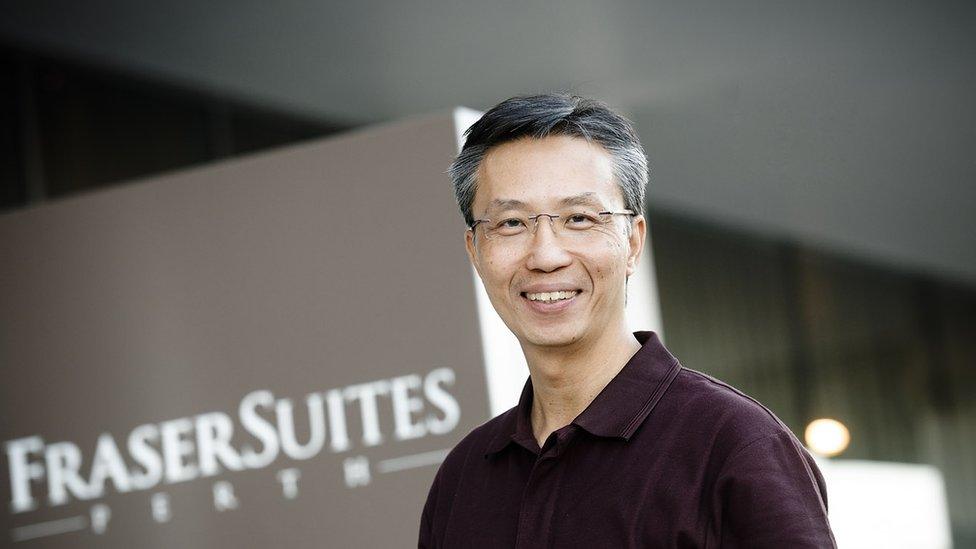

Choe Peng Sum launched Frasers Hospitality from scratch

On the first day in his new job, Choe Peng Sum was given a fairly simple brief: "Just go make us a lot of money."

Fast forward about 20 years, and it's fair to say he has done just that.

The business he runs, Frasers Hospitality, is one of the world's biggest providers of high-end serviced apartments. Its 148 properties span about 80 capital cities, as well as financial hubs across Europe, Asia, the Middle East and Africa.

But it almost didn't get off the ground.

When Mr Choe was appointed to launch and lead the company, Asia was booming; the tiger economies of Hong Kong, South Korea, Taiwan and Singapore were expanding rapidly.

But as Frasers prepared to open its first two properties in Singapore, the Asian financial crisis hit.

It was 1997. Currencies went into freefall. Suddenly, people were losing their jobs and stopped travelling.

Mr Choe recalls asking staff if they really wanted to continue working with the firm, because when the properties opened they might not get paid.

"It was really that serious," he says. "I remember tearing up because they said 'let's open it, let's open it whether you can pay us or not'."

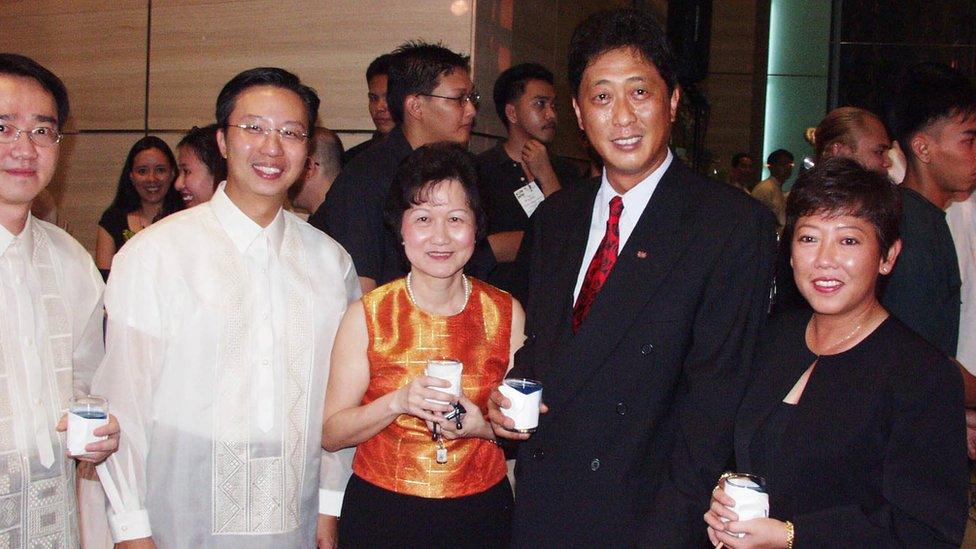

Choe Peng Sum (second from left) with colleagues at Frasers Manila opening in 2002

Survival, Mr Choe admits, came through a bit of luck, and the misfortune of others.

He had convinced the board at parent firm, property group Frasers Centrepoint, to open serviced apartments rather than hotels - partly because getting planning permission in Singapore was easier.

But he also sensed it was a big, untapped market. And at the time of the crisis, it proved to be exactly what customers wanted.

"As we were going through this difficult patch, there were protests and riots in Jakarta," he says. "A lot of companies like Microsoft called up looking for rooms for their staff because they were moving out of Jakarta."

Frasers' 412 apartments were quickly in demand. Occupancy soon hit 70%, and then 90%.

Explaining the popularity of serviced apartments, Mr Choe says that if people are staying somewhere for just a few days, they happily stay in hotels, but if they are going to be somewhere for one month to eight months, the walls of hotel rooms "close in on you".

But now, Mr Choe, 57, faces new challenges - the travel tastes of millennials and the disruptive nature of Airbnb.

"The way to tackle Airbnb is not to ignore it. I will never underestimate Airbnb," he says.

There's been no significant impact on Frasers yet. Big corporations still prefer to put employees in big service apartments, he says, because they can guarantee a level of safety and security. But that is likely to change, Mr Choe admits.

A former Edinburgh hospital has been converted into serviced apartments by Frasers-owned Malmaison Hotel du Vin

"I have two daughters who to my chagrin use Airbnb," he says. "We took a family trip to Florence and I stayed in this wonderful boutique hotel, but paid a bundle for it.

"When my daughter joined us, she said, 'I'm just staying next door and paying about 80 euros'. We paid about 330 euros.

"I asked why they stayed at Airbnb. They say 'it's like a surprise, it's part of the adventure'."

And so now, Mr Choe wants to bring some of that vibrancy to Frasers.

While neutral colours, beige curtains and dark wooden chairs dominate its more traditional apartments, many customers want something different, and this is shaping Fraser's strategy.

In 2015 it bought Malmaison Hotel du Vin, a UK hotel group that specialises in developing heritage properties into upscale boutique hotels.

That has taken them beyond financial centres, including to Shakespeare's hometown of Stratford-upon-Avon. Or, an intrepid traveller with $500 (£325) to spend could have a night in a converted medieval prison in Oxford.

And Frasers has launched the Capri sub-brand - whose website promises "inspiring art and inspirational tech".

Frasers' Capri Kuala Lumpur show the firm's typical interior designs

On a day-to-day basis Mr Choe says he still draws on his experience as a young man, who - having been given a scholarship by the Shangri-La hotel group to study at Cornell University in the US - came back to Asia to learn about the hospitality industry.

"They put me in every department conceivable. I remember one of the toughest jobs I had was in the butchery. I had to carve an entire cow. For one month, I could not eat meat.

"I'm thankful for those experiences. When you step into a hotel, you immediately pick up what works and what doesn't work.

"When I see the check-in staff walking more than three steps, I know the counter is set up wrong.

"It's like a cockpit. Can you imagine if the pilot had to turn around when he flies?"

More The Boss features, which every week profile a different business leader from around the world:

The 'diva of divorce' for the world's super rich

Mr Choe adds that loyalty is very important to him, and he remains tremendously grateful to staff who have stayed with him.

"I will always respect and remember those who gave up their jobs to join me," he says.

This loyalty is something that Mr Choe has earned, according to Donald MacLaurin, associate professor at Singapore Institute of Technology, and specialist in the hospitality sector.

Frasers is now a global business, with property around the world, including the Suites Le Claridge in Paris

Mr MacLaurin points out that Mr Choe introduced a five-day working week, in a part of the world where six days is common, thereby showing "a focus on quality of life issues for employees".

The associate professor adds says the early success of the business was remarkable given the timing of its launch.

Fast forward to today and the company is now on track to operate 30,000 serviced apartments globally by 2019. That success, say Mr Choe's admirers, should make him something of a visionary.

Follow The Boss series editor Will Smale, external on Twitter.