Future Energy: The computer brains making power plants more efficient

- Published

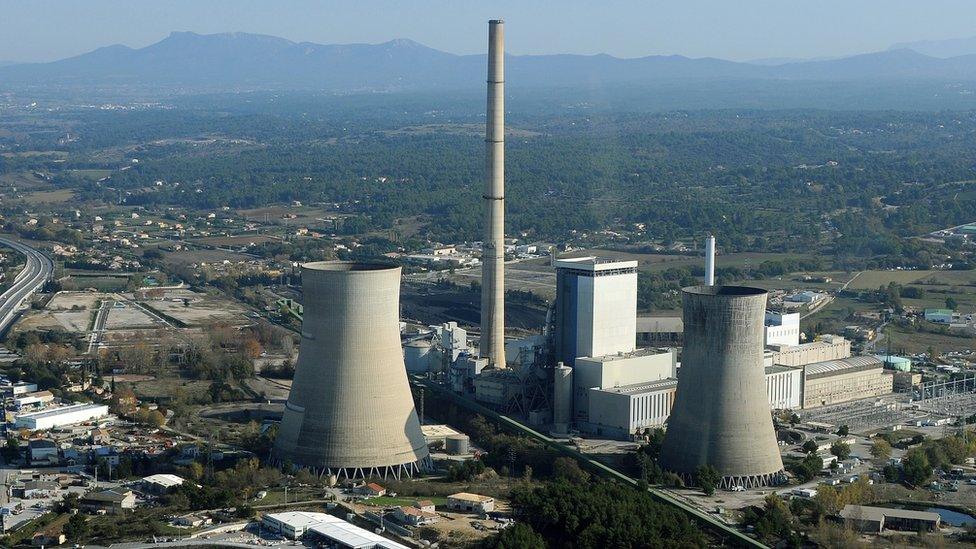

AI can be used to help make power stations more efficient

There are giant, complex machines out there that we all rely on. Without them, civilisation as we know it would collapse.

But these machines - power stations - are often pretty dumb, according to Peter Kirk, former chief executive of software company NeuCo.

"Power plants," he says, "are just robots that don't have a brain yet."

That is where his firm, acquired by GE Power last year, comes in.

For years, NeuCo had been developing optimisation technologies - a form of artificial intelligence or AI - that can make power plants more efficient.

The idea is to get a computer to monitor the hundreds of fine-grained controls that may be altered in, for example, a coal-fired power plant, and learn how to adjust them in a more effective way.

Human operators in such facilities are tasked with overseeing all kinds of minutiae, such as the level of oxygen in the furnace, the frequency of the soot blowers that keep tubes in the system clean, or the build-up of slag that, if left unchecked, can grow into huge boulders ready to break off and wreck the equipment.

Software is used to improve a power station's efficiency and stability

"There's too much data and it overwhelms the human ability to respond," explains Mr Kirk.

Instead, a computer can take over. Machine learning allows software to identify small changes that improve the efficiency and stability of the coal-firing system. The result, Mr Kirk says, is sometimes an efficiency improvement of about 1%.

That might not sound like much, but coal power plants are massive carbon emitters.

"I mean, that's 1,000 cars coming off the road," says Mr Kirk.

GE Power plans to develop this technology, which has already been used in many plants around the world. It has set up a new development centre at the Birchwood coal plant in Virginia.

AI, of course, is booming. The sophistication of machines that can recognise patterns or rules and automate a response to them continues to evolve at many firms - from those in retail to financial services.

But the tech is also cropping up in energy, not always the quickest sector to adapt to new technologies.

GE has another example of how AI can help - with wind turbines. The idea is to better predict the likely output from turbines, based on weather patterns, so that maintenance days can be more accurately scheduled for times when they are less likely to be operational.

The aim is to help reduce the amount of fuel a power station needs to produce the same amount of energy

GE has made very vocal advances into AI, and the firm clearly wants to be seen as something of a leader in this field.

But start-ups are getting in on the act, too. Pavel Romashkin, a 29-year-old from Los Angeles, has set up Volitant AI to provide optimisation services to clients such as factories, hospitals and power stations.

He is still in talks with some potential customers, but says that there are many ways in which AI could improve efficiency. Better forecasting of energy demand, for example, could help operators decide when to fire up generators with greater accuracy.

More from Future Energy

The challenge is in getting AI to respond to situations with the kind of nous we expect from it, of course.

"We as humans understand that New Year's [Eve] is a time when we use more power, but artificial intelligence doesn't know that, it just sees patterns," he says.

Computer brains can also be used to improve control at the other end of the energy supply chain - demand.

Google reported last year that it had been able to cut the energy used by cooling and support systems at its data centres by 15%.

AI from the firm's artificial intelligence division, DeepMind, was able to predict more accurately when cooling equipment - essential to keep hot servers running - should be switched on.

This was achieved by carefully analysing when people were more likely to access Google services like YouTube, and thereby increase the load on servers.

Engineers realised that it was more efficient at some times to spread the cooling load across lots of devices, rather than running fewer fans more intensively, according to Jim Gao, Google's data center engineer.

AI can also be used to help determine the best time to service wind turbines

But shutting cooling off entirely was not an option.

"If you shut off all the cooling you could probably go for a few minutes at most before your servers would melt or exceed temperature thresholds," he told the BBC.

Data centres consume gargantuan amounts of electricity, largely because of those cooling systems. It is no surprise, then, that other technology firms are trying to achieve similar results.

Chinese tech giant Huawei and Singaporean engineering firm Keppel recently announced that they have teamed up for a new AI-powered project.

The goal is to keep energy consumption low at a facility that will be one of the largest data centres in Singapore once it is built.

"It is a very hot topic," says Prof David Shipworth at University College London, referring to the rise of AI technologies in the tech and energy sectors.

"If companies can avoid doing upgrades [of physical infrastructure] and things like that, that can save hundreds of millions of pounds," he explains.

But he adds that his "instinct" is that the result does not necessarily help the environment as much as it helps companies to get more out of existing assets, particularly in terms of costs.

One firm that claims to have helped clients save thousands of dollars in existing, sometimes relatively old, facilities is BuildingIQ.

As with many systems out there, BuildingIQ's approach involves combining data about appliances actually consuming electricity with contextual information such as weather and energy prices. Then, controls may be more subtly managed.

BuildingIQ connects existing heating, air conditioning and ventilation (HVAC) systems up to a computer that essentially micromanages those appliances, according to Steve Nguyen, vice president of product and marketing.

Think of a building where the thermostat has been set to a certain temperature, say 21C.

"It's very hard for a mechanical system to maintain a particular set point," he explains.

Modern air conditioning systems are controlled by complex software

"Many buildings are set exactly that way - they suck up a tremendous amount of energy trying to maintain a specific point."

Instead, BuildingIQ's software aims to keep the temperature within a comfortable zone near to the desired 21C by making "microchanges" over time.

Because BuildingIQ's clients are keen to save money on electricity, the system can't just try to keep consumption low and forget about context - it also has to be sparing with those microchanges when energy prices are higher.

As market-watchers know, energy prices can fluctuate wildly within a single day based on, for example, peaks in demand and supply from variable resources like renewables.

But the firm claims a number of successes, including having saved a museum in Sydney $41,000 (£32,000) over 13-months, or 8.65%. No two clients are the same, however.

St Vincent's hospital, another Sydney client, was able to reduce overall consumption by 20% during its summer peak - but AI control over HVAC systems in operating theatres and intensive care units, for example, was out of bounds.

It has been building for many years now - NeuCo, for instance, was founded in 1997 - but using AI to improve efficiency seems to be an increasingly popular approach.

If smarter power plants and electrical appliances mean reduced emissions, and lower costs, for both supplier and customer, there's good reason to believe we'll see the trend continuing.