Top teacher fights for Canada's indigenous people

- Published

Maggie MacDonnell warned of high suicide rates among young people in Inuit communities

As a little girl growing up in rural Nova Scotia in Canada, Maggie MacDonnell was worried by locals gossiping about the Mi'kmaq indigenous people who lived on a nearby reserve. They said the Mi'kmaq were trapping on her family's land.

She recalls: "I went to my dad, a huge man, six foot something and in the woods a lot, and said, 'Dad you've got to watch out, the Mi'kmaq are hunting on our land.'

"He looked at me and responded, not in a chastising way, 'This is their land and we always have to remember that. They can hunt and fish and trap anywhere they want. We are guests on their land.'"

This year Maggie MacDonnell was named as winner of the Global Teacher Prize - and she links this accolade with these attitudes in her early years.

"I was lucky to have that influence at an early age," she explains.

"Because maybe other kids didn't go home and have that conversation with their parents, maybe they had a more prejudiced conversation."

Meeting presidents

Ms MacDonnell's understanding of the injustices meted out to Canada's indigenous people helped her work with students at Ikusik School in the 1,400-strong Inuit village of Salluit in northern Quebec on the Arctic circle.

It's an isolated place, accessible only by air, where young people have few job opportunities and where there have been problems with high levels of drink and drug abuse and shocking levels of suicide among teenagers.

At the award ceremony she spoke movingly of the experience of teaching in a school after a funeral of one of the students.

Maggie MacDonnell received the Global Teacher Prize at a ceremony in March

Her success was also remarkable because she had not even heard of the teaching prize, run by the Varkey Foundation, until she was nominated for it.

Sunny Varkey, founder of the Varkey Foundation, said she won the prize because of her "superhuman" tenacity in wanting to improve the chances of her students in Salluit.

"There are no roads to get there, the climate is tough and these communities are living with the legacy of generations of inequality.

"Due to the harsh conditions, where temperatures can reach -25C in winter, there are very high rates of teacher turnover, which is a significant barrier to education in the Arctic," said Mr Varkey.

"Many teachers leave their post after six months and many apply for stress leave, but Maggie has stayed on for six years, painstakingly building bonds with her students and instilling them with hope," he said.

Canada's 150th anniversary raises questions about how indigenous people have been viewed

But since the awards ceremony in Dubai in March, Ms MacDonnell has used the prize to highlight the needs of her students.

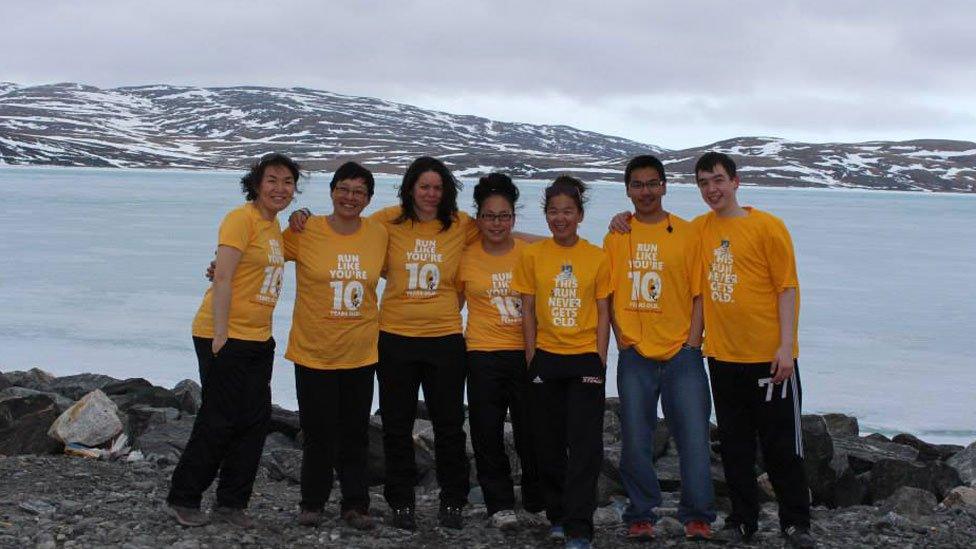

She took Inuit students and teachers to the Toronto Film Festival to show and discuss the documentary film Salluit Run Club, external about the running club she set up to try to build up the resilience of her students and the local community.

"The young people I brought opened up all sorts of conversations for parents to have with their kids on indigenous issues in Canada. It was awesome," she says.

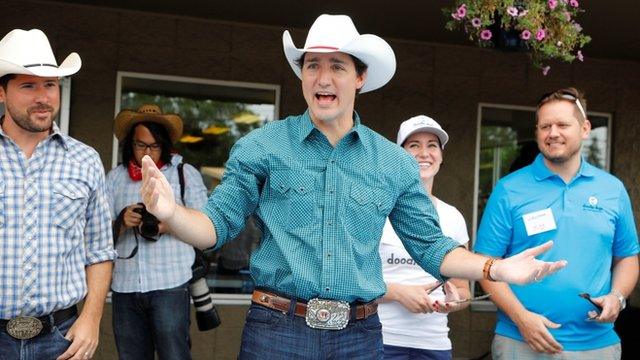

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau wants reconciliation with Canada's indigenous people

Two of her students went to the United Nations in New York for a one-hour conversation with former US president Bill Clinton.

On a visit to Chile, two students met the country's president, Michelle Bachelet, and were guests of the indigenous Mapuche people.

President Bachelet publicly asked the Mapuche and other indigenous people for forgiveness for the historic injustices.

"That was an amazing moment for the Inuit youth who I work with to witness and be part of," said Ms MacDonnell.

Pressure on indigenous people

Last week, thanks to the funding from the prize, she took four young Inuit people to her own home turf of Nova Scotia to take part in her newest initiative, a kayaking project.

It is a one-week course designed to give them a basic kayaking certification to build their confidence on the water.

Maggie MacDonnell founded a running club to provide something positive for young people

The kayak is a potent Inuit symbol. It once enjoyed a more prominent place before pressures like enforced residential schools separated Inuit youth from traditional cultural and economic roles.

It was an emotional visit. There were already connections in place. Her social worker sister Claire has adopted two Inuit children from her time in Salluit (she was there before Maggie), and her mother had also visited the village.

Maggie's work and her prize have helped highlight the struggle of Canada's indigenous peoples.

Canada has been marking its 150th anniversary - Canada 150 - and as part of this commemoration prime minister Justin Trudeau highlighted the "victims of oppression".

"As a society, we must acknowledge past mistakes," said Mr Trudeau, about the need to acknowledge previous wrongs to indigenous people and to achieve future reconciliation.

While Canada celebrates 150 years, Inuit people have been there much longer

The comment chimes with Maggie MacDonnell's teaching experience. Her Inuit community has been in the region for thousands of years, and the past 150 have not been kind to them, so even those who are proud Canadians may have had trouble celebrating Canada 150.

The Nunavik region, made up of 14 villages that include Salluit, suffers from a chronic housing shortage.

This exacerbates other problems which include alcohol and drug dependency and a high rate of tuberculosis.

Maggie MacDonnell's work with indigenous people in Canada also has resonances elsewhere.

Global warming

She has worked in Tanzania and wants to take Inuit students to climb Mount Kilimanjaro with local youth "to bring more attention to an African symbol of climate change, because on Kilimanjaro the glaciers are melting".

Ideas for the Global education series? Get in touch.

Her own community is already aware of the impact of global warming. Her students posted on Facebook a picture with a brown bear taken locally.

"That's ridiculous," she says, "like seeing a giraffe walk through London." They are usually found much further to the south.

"We need to collaborate on a global level," she said. "There are opportunities to weave together global issues, particularly for indigenous people, and especially climate change, social justice, gender empowerment."

The teacher prize has brought attention to the Canadian Arctic

The ambitions may stretch internationally, but Maggie MacDonnell's work is firmly grounded in her community.

On the theme of Canada 150 she said: "I guess you can say that education does offer opportunities for reconciliation.

"I think that if Canada can seize this opportunity and become a global leader and an example for healing relationships between our indigenous and non-indigenous people, that's when we are going to be a truly developed country.

"I wish that all Canadians could see the benefit of how we would all be richer, not just economically, when we really start to value and ensure that indigenous people can unlock their full potential.

"What Canada could look like then would be phenomenal. When we embrace all that diversity and all those different outlooks, that's what would make Canada so exciting.

"Canada 300 - a really great party that I'd like to come back to if possible."