Can hi-res music hit the right note?

- Published

Arcade Fire's Everything Now is the most popular hi-res album on the Qobuz site

High-resolution sites are proving music to the ears of fans who want the best possible sound.

Ever since the first CD was produced - 35 years ago this month - the music industry has been trying to sell fans new formats on the basis of better sound quality.

The shiny silver discs were meant to banish the crackle and hiss of vinyl forever and were marketed as a boon for audiophiles.

But at the same time, they were more convenient, being smaller and offering the chance to play tracks in any order you liked. And you didn't have to turn them over to hear the second half of an album.

What record company executives didn't realise was that it was the convenience, rather than the better sound quality, that was the main draw for consumers. That's why the rise of the relatively low-quality MP3 file caught record companies on the hop.

The download is fading from popularity as consumers embrace streaming instead, but most streamed music services use the same digital compression techniques as MP3 files did.

So is top-notch sound quality no longer important? Some firms disagree and are promoting high-resolution digital music.

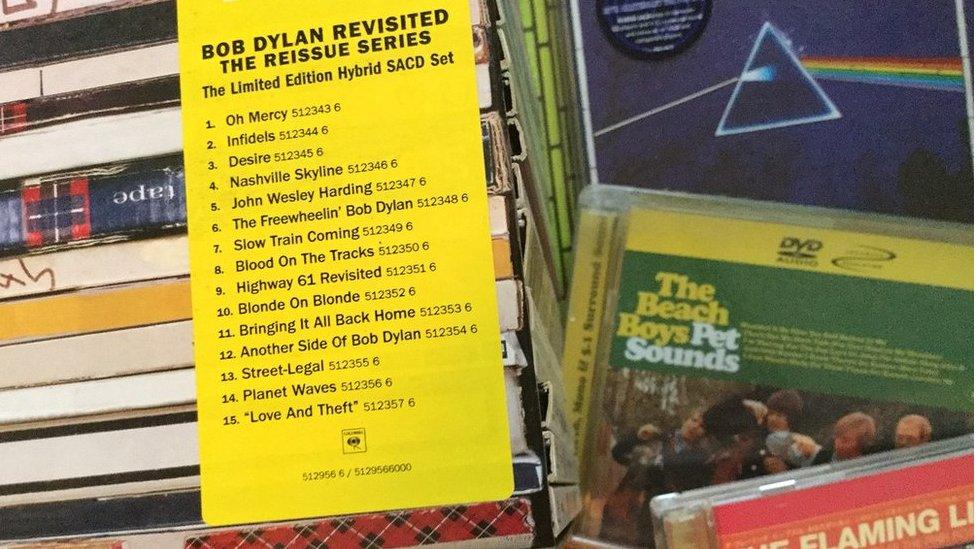

The SACD and DVD-Audio formats failed to fly

"Is MP3 as interesting as it was 10 years ago? Not really, because bandwidth has improved," says Malcolm Ouzeri, head of marketing at French streaming and download provider Qobuz, external, founded in 2007.

"Now the industry is going towards more quality."

The music industry placed bets on high-end sound quality before. It came up with two new types of silver discs - the Super Audio CD (SACD) in 1999, followed by the DVD-Audio disc a year later.

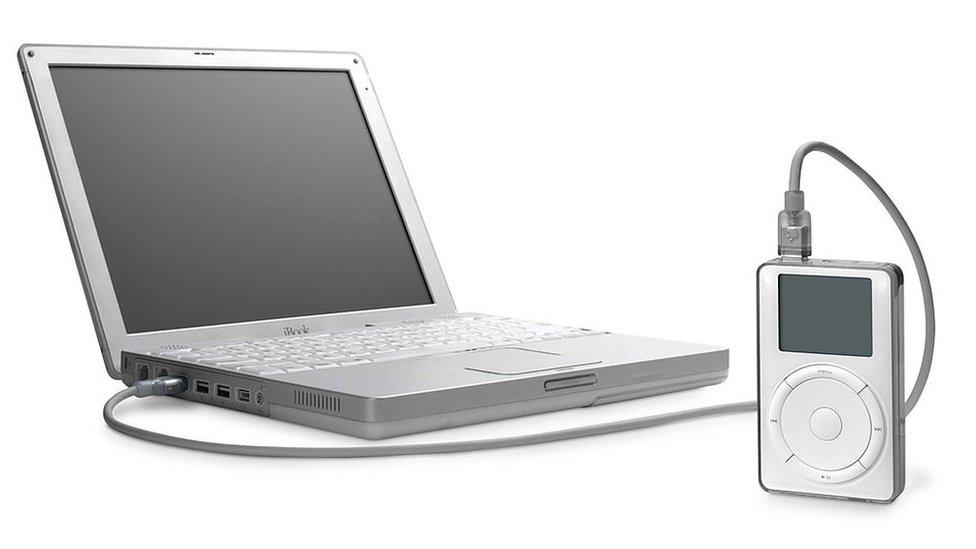

The ensuing format war, plus the need to buy new hardware, didn't help matters. But what really killed their chances was the launch of Apple's iPod in 2001, which established the compressed MP3 digital file as the mass-market way to hear music.

"Like Monty Python's Spanish Inquisition, nobody expected the iPod," says independent audio consultant Garry Margolis, external.

Apple's first iPod went on sale in 2001

"Apple made it easy for the average consumer to buy music and carry it in a convenient package.

"The money that consumers would have spent on high-resolution surround sound instead went to portable music, and the demand needed to establish a viable hi-resolution format never materialised."

But now, nearly two decades later, another business model for high-end audio is up and running. In its native France, Qobuz has 4% of the digital music market with its unashamedly niche offer of uncompressed streams and downloads.

More Technology of Business

"Our goal is to be a service with one million customers worldwide," says Qobuz chief executive Denis Thebaud.

"Qobuz is not a brand for everyone. It's not a brand where we want to have 100 million users. Our goal is really to satisfy the most discerning music lovers, the ones who are the most passionate about music."

And at £349.99 a year for its top-end Sublime+ service, offering both streaming and downloads at the highest quality, only those with deep pockets as well as sensitive ears are likely to be signing up to the site.

Lana Del Rey's latest release, Lust for Life, is proving popular with Qobuz users

Some kinds of music are really not well served by the MP3 system of encoding, which is designed to preserve the elements that the human ear can hear and discard the rest.

Classical music aficionados, for instance, have never been keen on that kind of sonic compression.

But Qobuz, along with rivals Tidal and Deezer Elite, offers streaming of "lossless audio" that throws nothing away.

The highest quality MP3 has a bit-rate of 320kbps, while a hi-res file can go as high as 9,216kbps. Music CDs are transferred at 1,411kbps.

"The artists want to have their music played as it was recorded. More and more albums are in hi-resolution," says Mr Ouzeri.

Neil Young is planning a new hi-res streaming site

This means that musical genres traditionally associated with hi-fi buffs are particularly popular on his firm's service.

"On Qobuz, different things are being listened to. At the end of the day, more royalties go to those things that have difficulty surviving in the digital world," Mr Ouzeri adds. "Classical music and jazz have this important role."

If you're looking for hi-resolution downloads in the 16-bit or 24-bit Flac format, Qobuz also offers those, as do other sites including 7digital, external.

Other services, such as Neil Young's now-dormant Pono venture, have tried and failed to enter the same download market. However, the rocker has vowed to return to the world of hi-res music, external with Xstream, which he calls "the next generation of streaming".

Qobuz thinks there is still demand for downloads, and Mr Thebaud points out that some labels, including esoteric jazz specialist ECM, only offer that option rather than streaming as well.

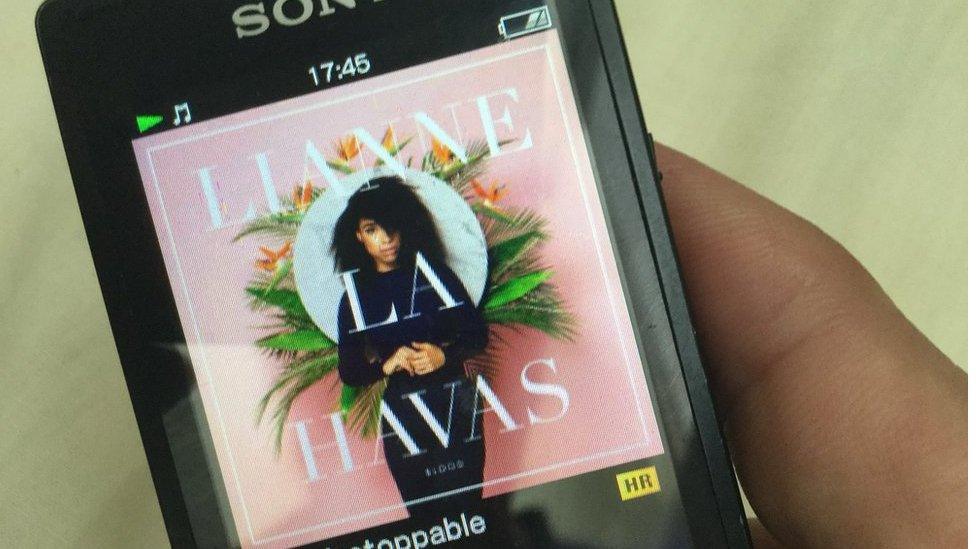

A large number of portable music players can play hi-res downloads

But does hi-res music face the same hardware problem that helped to sink SACD and DVD-Audio?

As it happens, a whole range of portable music players has sprung up to play hi-res downloads. Some are from mainstream manufacturers such as Sony and Pioneer, while others are produced by specialist firms such as Astell & Kern. Prices range from £165 to £3,000 or more.

But when it comes to streaming, there are various inexpensive options that will do the job.

"The Chromecast dongle, for instance, supports hi-res," says Mr Ouzeri. "MP3 does not make as much sense as it did 10 years ago. So we are pioneers and we will keep being pioneers."

Meanwhile, back in the world of physical product, the CD soldiers on, while vinyl has raised its game considerably in the audiophile stakes.

Sales of vinyl records have rebounded in recent years

It hasn't become any more convenient as a format, but today's heavyweight 180g vinyl album release is a real improvement on the lightweight pressings, often made with recycled vinyl, that were the norm in the 1970s.

The vinyl revival has been well documented, with 3.2 million LPs sold in the UK last year, but do SACDs still exist?

Sister Ray in Berwick Street is one of the few record shops left in London that still stocks them, but you won't see much change from £30 if you want to pick up a choice Bob Dylan or Miles Davis title in the format.

And as senior buyer Steve Sexton makes clear, they don't quite fly off the shelves. "It's always been quite a niche format. We're phasing them out, to be honest," he says.

"I think it's a bizarre format and I've never really understood it. A lot of it is people who've spent far too much money on their stereo system."