Obama treasury secretary: Financial risks 'substantial'

- Published

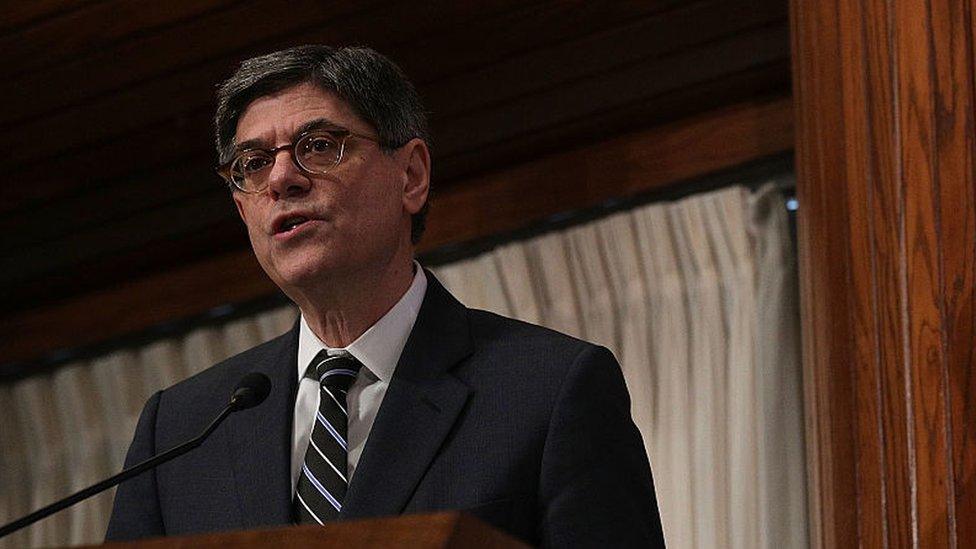

Jack Lew was a financial adviser to President Obama at the start of the crash

Jack Lew, former US treasury secretary, has told the BBC the world remains at risk from financial threats.

He says loosening regulation would not be a good idea: "We should not disarm at a moment when we're out of the last financial crisis, but still in a world with substantial financial risks.

But Mr Lew, an adviser to Barack Obama during the financial crisis in 2008, says no to tighter rules.

"I don't personally believe we should do more than we need to."

Looking back on the unfolding financial crisis, he told the BBC's Today Programme the bad news had kept on escalating.

"I have never seen a situation where every single day the numbers were so much worse than the day before that you literally had to keep revisiting how much fiscal stimulus the economy would need in order to stimulate a recovery," he said.

He said action taken then, both in supporting the financial system and tightening up regulation, had borne fruit: "What our reforms of Wall Street after the crisis did was, for the first time since Great Depression, give us the tools to safeguard the evolving financial system."

Close eye

The Dodd-Frank Act was the key piece of law-making designed to ensure there would never be another 2008-style meltdown.

Its aim is to keep a closer eye on the institutions that are "too big to fail" and to limit the risks they take.

President Donald Trump thinks regulation of the financial sector is now too onerous.

One part of the Dodd-Frank act is the Volcker Rule, which is designed to prevent banks from using their own money to trade.

Last week, that was officially opened up for review, after Trump appointee Keith Noreika announced he wanted views on how to define better which activities are prohibited by this rule.

Mr Lew gave a warning on making significant changes to the rules: "There's been a big push back saying this has gone too far.

"I fear that as the memory fades, some of the simple nostrums about clearing away regulation start to take on salience, as if the stakes weren't high enough in 2007-08."

But although he thinks the level of regulation is currently sufficient, he says there are no guarantees that these existing rules will prevent a new major financial shock.

"The risks in the future are unlikely to come from the places they've come from in the past," he said.

"We all know crises will come in the future, what we don't know is when and how."

Analysis: Andy Verity, economics correspondent

Are we, the taxpayers, safe from having to bail out a bank ten years on from the credit crunch? The short answer is: safer than we were ten years ago. But not 100% safe.

Reforms brought in since the global financial crisis are supposed to mean a bank could simply go under without causing a collapse of the financial system or requiring the government to bail them out. The idea is that banks should be like normal private companies which take their own risks; if executives screw up, shareholders and creditors might lose money - but taxpayers shouldn't.

But buried in the Bank of England's recent financial stability report is an admission that that's not yet the case. We are merely "on course" to achieve that by 2022. The implication is that if a bank went under now, taxpayers would still probably have to intervene.

Is that at all likely? For a bank to go under, its losses would have to exceed its capacity to absorb them. Post-crisis reforms have required banks to have more capital set aside to absorb losses. The Bank of England's highlighted the fact that they now have to hold "10 times" more capital in case things go wrong. Which sounds reassuring until you realise how little they had to hold before the crisis. Under the old regime (known as Basel II) there was no "leverage ratio" - no cap on the amount banks could lend for every £1 they had in loss-absorbing capital. Now there is a cap of 3.25% - so that, put simply, banks have to have £3.25 set aside in capital to absorb potential losses for every £100 they lend. Ten times hardly anything is still not a vast amount.

Having said that, for banks to chalk up losses of £3.25 for every £100 they have lent would require an economic calamity on a scale to beat even the crisis of 2008. That risk seems comfortably remote - or at least, we had better hope it is.

- Published2 August 2017

- Published5 August 2017