RBS restructure client: 'I became suicidal'

- Published

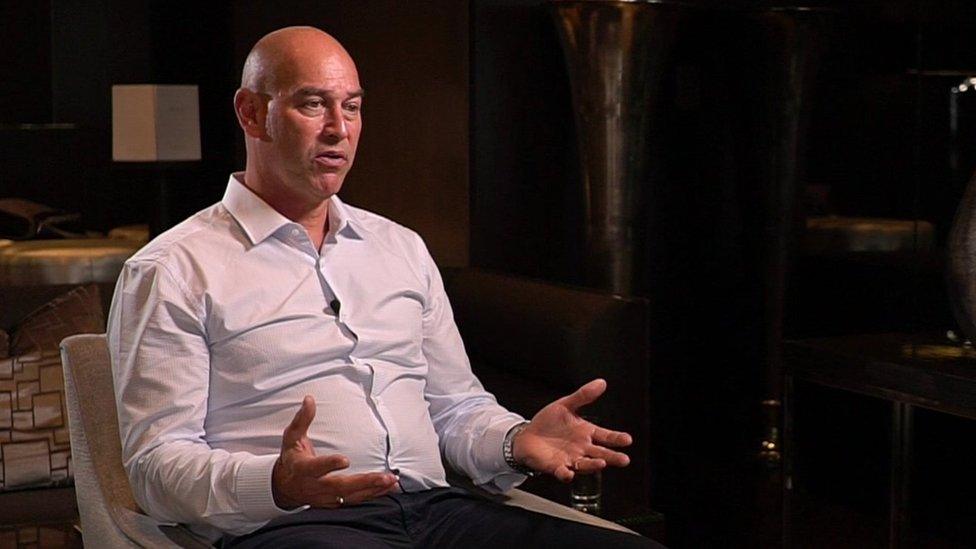

Tracy Standish ran a family business, Bowlplex, that his father had started in Poole.

The business, which was healthy until the recession hit, banked with RBS.

The firm had 18 outlets when the global downturn began, but the recession was "dramatic in its impact", he said.

"It just stopped foot flow in the most dramatic way, and we saw sales slide by 10%. Before we knew it [it] was 15%, and then it went to 20%, and we were powerless to do anything about it."

The ratio of profit to debt fell below a certain level, and the firm found itself in "breach of covenant" with the bank - which basically means it could not meet the conditions of its agreement with the bank.

This raised a red flag with RBS, and Bowlplex was handed over to a part of the bank known as the Global Restructuring Group (GRG) "on the basis that they were going to have the specialist knowledge and team to help us improve our position and get through the difficulties we were facing", Mr Standish said.

'Very aggressive attitude'

From 2010 for around four years the GRG team, which had initially been "nice as pie", became "like the Gestapo walking in", he said.

"Their aggression, their divisiveness, the whole way in which they talked. They would bang tables, shout, point fingers - the whole thing was like they weren't in any way here to help us through a difficult time.

"They were trying to subjugate us, subjugate the board, and by consequence, the family ownership of the business."

He said GRG added to the firm's problems "because they were adding costs, insisting on additional professional bodies coming in and doing reports on our performance, increasing our fees, and taking a very aggressive attitude."

They wanted personal guarantees on the overdraft facility, and they "were obsessed with that for a period of time before they ultimately gave up on that", he said.

As part of the first debt restructure the bank identified a part of the debt as being high risk, and determined a higher rate of interest, at 15%, which "put the company under greater duress" and there was "a greater demand for cash to be set aside".

Then the bank said it wanted a stake in the business to avoid pulling loans.

"It became very obvious that their interest was in the equity," said Mr Standish.

'They fired me'

Mr Standish expected RBS to take a 10% or 20% stake in the business, but for RBS to continue its support, which allowed the firm to pay the monthly wages, RBS "demanded 80% of the company".

It was a choice of that, or the firm falling into administration, he said.

The restructuring took the best part of two years.

"At the end of the process, the bank engineered through two stages to take 80% of the equity away from my family," he said.

"They had control of the company, they introduced a chairman to effectively become my boss, and that was the price that we paid as a family for the bank to continue supporting a business that had been successful for... nearly 30 years, but had run into the very damaging consequences of such a deep recession.

"They fired me as part of that process."

He said dividends to the family had been paid "quite with the blessing of the bank".

'Business not viable'

Mr Standish said that he was "devastated" by the actions of the bank.

"It was to suddenly not know where to go, to be completely lost. It was like an out of body experience. I just really didn't know what had happened to my world, and where to go next," said Mr Standish, who lives in Poole.

"I must have been in shock maybe for a month... That just descended into full blown depression.

"I had to be referred to a counsellor for treatment, I was prescribed anti-depressants. And I became suicidal, and was so, for some period."

Mr Standish is now suing RBS.

The bank said that the Standish case was currently the subject of litigation and that it would be "vigorously defending these claims".

RBS said when Mr Standish's firm Bowlplex came into the Global Restructuring Group, the shares he held were of little or no value because the value of the company was less than the debt and the business was not viable in its current state.

The firm had paid out £4.3m of dividends to the family in the seven years before 2008, it said.

As a result of the support it provided - including writing off £4.6m of debt owed to the bank - the company was sold for £30m. The net effect on the value of their shareholding was significantly positive, even though the percentage of the company they owned reduced, it added.

- Published25 August 2017

- Published12 July 2017

- Published6 June 2017