Does the US debt of $20tn matter?

- Published

US debt is soaring. Does it matter?

Republicans are planning to pass a massive tax cut, despite their own avowed fiscal conservatism and warnings the legislation could increase the federal deficit by at least $1tn.

US national debt passed $20tn earlier this year, so could the imprudence of lapsed budget hawks clip the wings of the American economic eagle?

What's driving the rising debt?

More than half the 2016 budget was spent on retirement and healthcare programmes. As the US population ages, that's expected to grow.

The debt itself is fuelling the fastest-growing spending item, external: the Congressional Budget Office expects annual net interest payments, which totalled about $240bn in 2016, to hit $770bn in 2027.

The US ran an average budget deficit of 2.8% of GDP between 1967 and 2016.

But that increased in recent years, spurred by the Great Recession a decade ago, when tax revenue dried up and the government increased its spending to try to spur a rebound.

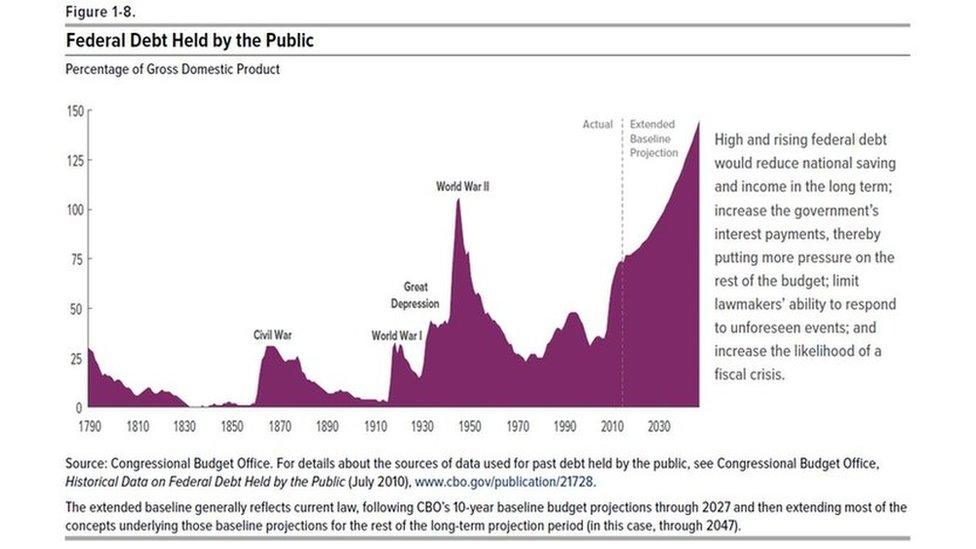

Historically US debt has tended to spike during wars and economic crisis.

Total debt, including obligations to programmes such as Social Security, more than doubled between 2000-10, when it exceeded $12tn.

It represented 128% of GDP last year, according to the OECD, external.

That was lower than Portugal (146%) and Greece (185%) similar to the UK (123%), but more than double Denmark (53%) and Sweden (60%).

Is this a problem?

Economists argue that high levels of public spending crowd out private investment, eventually hurting growth.

A high debt load could also constrain the options of the US the next time it needs to borrow.

In recent years, concern about the debt has subsided, since borrowing costs have been unusually low.

The US has been "spoiled" by low interest rates

"We've been kind of spoiled by low interest rates," said Eric Freedman, chief investment officer at US Bank Wealth Management.

But he warns that if government interest rates rise it "would potentially impact future social programmes".

Analysts say the US has the capacity to sustain high borrowing levels.

But there are concerns about the medium-term debt, says Charles Seville, a senior director at Fitch Ratings, which gives the US its top credit grade of AAA.

"Unlike most other very highly rated countries the debt is increasing," he said.

How much does US owe foreign nations?

Foreign investors - including governments - owned $6.25tn, or more than a quarter of total US debt at the end of July, external.

Chinese investors were the largest foreign holders of US debt at $1.1tn, followed closely by investors from Japan.

The increasing role of foreign investors is a shift from earlier decades, when most US debt was owed domestically.

Chinese investors were the largest foreign holders of US debt at $1.1tr, followed closely by investors from Japan. About 70% of the foreign holders were governments in 2016.

If foreign demand suddenly changed, the US would be vulnerable, said Karen Dynan, a Harvard economist who served in the US Treasury Department under the Obama administration.

"Anything that could produce a sharp swing in that demand could have the potential to raise rates on our debt in a way that would make our fiscal position worse," she said.

Is a 'Suez moment' nigh?

Higher interest rates for the government would hit the private sector, raising costs for borrowing.

It could also have geo-political repercussions.

The UK faced a somewhat similar dynamic in 1956, during the Suez Crisis, when it wanted to take military action after Egypt nationalized the Suez Canal Co.

At the time sterling was under pressure, but the US refused to provide help unless the UK ceased the military action.

However, the mighty US dollar remains the linchpin of the global economic system for now.

Economists say the US need not ever pay its debts back entirely, so long as the economy keeps growing enough to cover the payments.

But because of the risks, they point out, it's prudent to reduce the current load.