Why big brand perfumes may be losing their allure

- Published

Nick Steward is the founder of Gallivant fragrances

Corporate giants such as Estee Lauder, L'Oreal and Coty have dominated the fragrance market, but could that be about to change?

"Everything smells the same - people are getting bored of the big brands and want something different," says Nick Steward, the London-based founder of a new fragrance brand, Gallivant.

He is convinced that there is a growing appetite for "something more personal that other people don't have".

Mr Steward decided to start his own company after several years as creative director of the trendy Paris house L'Artisan Parfumeur.

"I wanted to do something clever and interesting, avoiding all the froth, focused on the best materials," he says.

He now sells his fragrances online and via specialist retailers in the US, Italy, Germany and as far away as Australia.

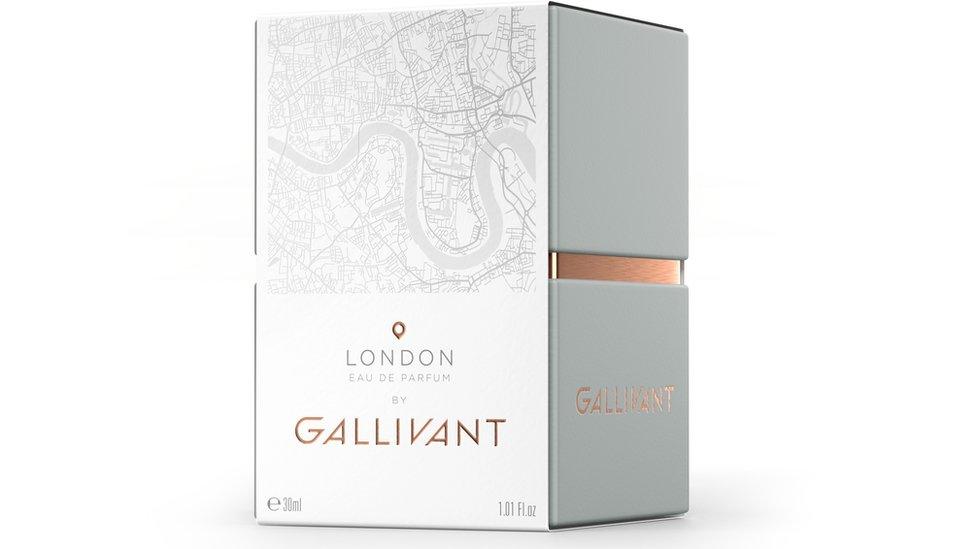

Gallivant fragrances are smaller than the standard industry size

The Gallivant range of unisex fragrances are inspired by and named after cities such as Tel Aviv and London.

They are packaged in air-travel-friendly 30ml bottles - smaller than the standard industry sizes.

Mr Steward says that also makes them more affordable, reflecting consumers' desire to have a variety of fragrances to choose from.

Reception from both consumers and retailers has been positive since the launch earlier this year, but he admits the road to profitability will be a challenge: "It's a really tough business to make money in."

He is seeking a slice of the fragrance market - worth about $27bn (£20bn; €22bn) a year globally - but it is dominated by corporate giants such as Estee Lauder, L'Oreal and Coty.

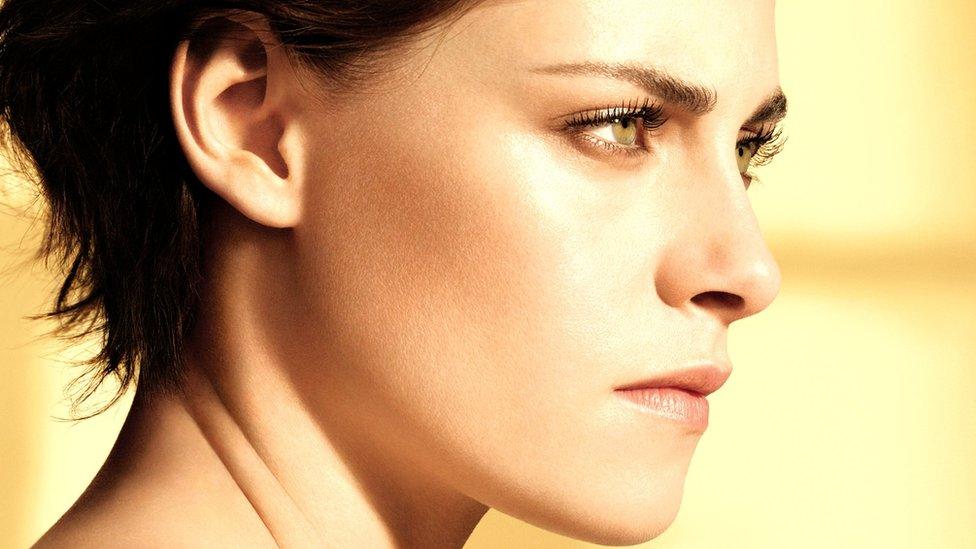

Chanel's latest campaign stars Kristen Stewart

These firms spend tens of millions of dollars a year in a bid to make their fragrances seem impossibly alluring to consumers, using celebrities such as Kristen Stewart, star of the latest Chanel campaign, or Charlize Theron, who features in ads for Dior J'Adore.

Seeing glamorous ads on TV, in the cinema or in magazines means consumers are more likely to try, if not buy, one of the hundreds of perfumes on the market.

Despite the daunting competition, Michael Edwards, publisher of global perfume database Fragrances of the World, says some consumers are favouring niche and artisan fragrance brands like Gallivant because they offer something special that none of their friends will have.

He believes that innovation in the sector is coming from smaller brands because the big players are afraid of taking risks.

The big brands want a new launch to appeal to as wide a range of consumers as possible, meaning they often produce something "bland", he says.

Coty, behind brands including Gucci Bloom, reported a loss in August

"The future lies in bespoke - younger people want something of their own. While marketing is crucial, word of mouth is even more crucial," says Mr Edwards.

The fact that some of the bigger names in the industry are struggling suggests he may be right.

Even Coty - the New York beauty brand behind famous names such as Calvin Klein, Marc Jacobs, Gucci, Hugo Boss and Chloe - has faced headwinds this year.

In August, it reported a surprise quarterly loss that was partly blamed on "materially" higher marketing costs for the launch of new fragrances, including Gucci Bloom and Hugo Boss Tonic.

L'Oreal, which sells fragrances under brands including Yves Saint Laurent, Ralph Lauren and Diesel, also reported disappointing sales and profits for its most recent quarter.

Michael Edwards founded the Fragrances of the World guide

But Roshida Khanom, an analyst at market research firm Mintel, says the industry giants are not taking the threat from upstart rivals lying down.

Chanel, one of the world's most well known perfume makers, has revamped its range, launching No5 L'Eau in time for the Christmas rush last year.

The new version of Chanel's classic fragrance - aimed squarely at younger generations - helped boost sales of the No5 range by a fifth.

At the same time, the French company also launched its first new fragrance in 15 years last month, Gabrielle, with a big-budget ad campaign.

What do people want from a perfume?

The experience of wearing the fragrance - not the bottle or the packaging - is still the most important thing for consumers, says Michael Edwards, publisher of global perfume database, Fragrances of the World.

Most people want a scent that is "pretty easy to like", he says.

A fragrance has to entice at first sniff with a compelling "top note", and convince the buyer that it will linger sufficiently long on his or her skin.

Above all else, he says: "It must make the wearer feel special."

Retailers will be hoping that the launch will help return the fragrance sector to modest growth in the UK after two years of what Ms Khanom calls "disappointing sales".

Mintel estimates UK sales will be worth about £1.5bn this year, making it the fifth-biggest market globally behind Brazil, the US, Russia and France.

As with other retail sectors, she says one of the problems is savvy consumers who try out products in a physical store but then go online to buy it for less.

Manufacturers are spending more on the bottle and packaging, as well as marketing, in a bid to get consumers to buy their fragrances.

Some consumers think celebrity fragrances are "tacky"

But the power of another popular trick - releasing a fragrance emblazoned with the name of a celebrity, such as Britney Spears, Beyonce or Jennifer Lopez - appears to be waning.

Mintel says that a third of consumers describe this approach as tacky.

"Celebrity fragrances are just not aspirational in the way they used to be," says Ms Khanom.

Of course, for Gallivant's Mr Steward this is good news.

But while some Gallivant buyers want it to remain a tiny brand only they know about for "bragging rights", Mr Steward says that is not sustainable.

"I can't live just selling five bottles a year."