'Tell me phone, what's destroying my crops?'

- Published

Voruganti Surendra says farmers are finding pest and disease recognition apps "very useful"

India's farmers have never had it easy; drought, crop failure, low market prices and lack of modernisation have taken their toll on the nation's population, about half of whom work in agriculture.

Every year thousands of farmers take their own lives. So can crop management apps help?

Voruganti Surendra is a farmer who grows paddy rice on an acre of farmland in Guntur District, Andhra Pradesh.

He and hundreds of his fellow farmers are using a new app that can recognise a growing number of crop pests and diseases and give advice on how to treat them.

"It is very useful," he says. "Farmers need it."

The app, called Plantix, was developed thousands of miles away in Berlin, Germany, by a group of graduate students and scientists who came together to help farmers combat disease, pest damage and nutrient deficiency in their crops.

"It was really important for us to understand what farmers wanted," says Charlotte Schumann, co-founder of Peat (Progressive Environmental & Agricultural Technologies) the company behind the app, "so we did a lot of groundwork in India".

Peat boss Simone Strey (left) and co-founder Charlotte Schumann created the Plantix app

After months criss-crossing this vast country by train, conducting research in rural areas, the team concluded that a diagnostics app featuring image recognition would help farmers most, especially since smartphone prices were falling to affordable levels.

"The smartphones gave many of them access to the internet for the first time," says Ms Schumann.

There are 500 or so farmers in Mr Surendra's village of Karlapalem in Bapatla Mandal, growing rice, maize, cotton, banana, chilli and a host of other crops.

While just 20 own their own smartphones, these lucky few share them so that their fellow farmers can take photos of their crops and upload the images to the app.

The farmer photographs the damaged crop and the app identifies the likely pest or disease by applying machine learning to its growing database of images.

Not only can Plantix recognise a range of crop diseases, such as potassium deficiency in a tomato plant, rust on wheat, or nutrient deficiency in a banana plant, but it is also able to analyse the results, draw conclusions, and offer advice.

The app can recognise different types of pest damage and suggest treatments

These abilities rely on deep neural networks, or DNNs, which processes information in a way similar to how biological nervous systems operate.

"It works a bit like the human brain," says Peat's chief executive, Simone Strey.

Initially, or if the image recognition software gets confused, pathologists and other experts will provide information about what the app is looking at.

"Obviously, it needs some backup from human experts," says Ms Strey.

The app had to be multi-lingual because "the farmers often use different names for crop diseases than those used by scientists", she says.

"And if the farmers don't know the scientific name, they won't be able to search for solutions online."

It is currently available in Hindi, Telugu and English in India, and in five other languages for use in other countries.

About half of India's 1.3 billion people work in agriculture

But Peat is not the only firm developing smartphone apps to help farmers.

In Africa, for instance, the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research - a body dedicated to food security - has just won a $100,000 (£76,000) award to expand its research and bring a similar app to farmers across the continent.

David Hughes of Penn State, who co-leads the project, describes it as "transformative" and says they "can amplify by 100 times what we have achieved so far".

In fact, the number of digital helpers that can fit in farmers' pockets has grown dramatically in recent years.

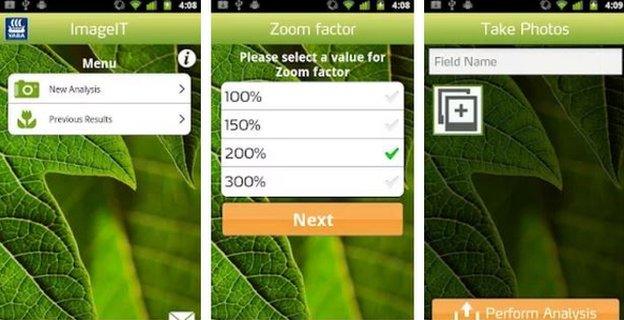

They include fertiliser firm Yara's ImageIT app, which uses photos to measure nitrogen uptake in a crop and offer recommendations to farmers.

University of Missouri's ID Weeds app helps farmers identify unwanted plants. And John Deere's GrainTruckPlus app helps with grain harvesting storage and fleet logistics.

Then there's PotashCorp's return-on-investment calculator, called eKonomics, and AgVault 2.0 Mobile's Sentera app, which controls drones that can systematically film entire fields autonomously and feed back the footage for analysis.

Yara's ImageIT app aims to measure the nitrogen content in plants

"Technological innovations play a very important role," says Harsimrat Kaur Badal, India's Minister of Food Processing Industries, in reducing waste, improving hygiene, creating jobs, and addressing "farmers' distress".

Krishna Kumar, chief executive of CropIn Technology, a data-driven farming company, believes agricultural "start-ups [will] innovate fast and change every aspect of the industry".

While such apps are practically useful to farmers now, it is the data they collect that is potentially more useful in the longer term, argues Peat's Ms Strey.

"Each farmer represents a data point, and it's really the data set that's valuable. Research on this scale in this field hasn't been done before by any global research organisation."

This is why farmers don't usually have to pay to use such apps.

"If you want to collect data, you don't make the users pay," says Ms Strey.

More Technology of Business

Peat's database currently contains some 1.5 million images - up from 100,000 a year ago, with 80% of its 300,000 to 400,000 users currently in India.

Geo-tagging offers insight into which plants are grown where, and whether or not they are healthy. Apps can record the weather, too, and build up a picture of the climatic conditions.

Such knowledge is valuable not just to the farmers themselves but also to producers of fertilisers or pesticides, to the food industry which wants to source crops, and to governments keen to see the bigger picture in their countries.

As such, the challenge, according to CropIn Technology's Mr Kumar, is not merely to gather the data, but to "make sense of it and present it as actionable insights to agri businesses".

Follow Technology of Business editor Matthew Wall on Twitter, external and Facebook, external