From torture victim to human rights student

- Published

Noura Al Jizawi has come to study in Toronto after escaping Syria's civil war

Noura Al Jizawi has survived more than a decade of extreme risk. Now she's going back to her interrupted life as a student.

Growing up in Homs in Syria, the 29 year old has been a student activist, experienced imprisonment and exile and has been a leader in Syria's opposition.

Now eight months pregnant, she has gone back to her studies, beginning a master's degree at the University of Toronto's Munk School of Global Affairs.

Noura's first awareness of human rights - and of their absence - came early: "I remember when I was just a kid, I was angry because we couldn't choose our notebooks.

"We could have only one type of notebook - one with a photo of Assad's father on it."

Missing persons

She soon learned that other, much worse things were wrong with her country.

Homs this summer showing the damage of war

"Many of the students, a couple of years older than me, were mentioning their missing fathers. I became aware we had missing persons in Syria.

"While I was growing up, I remember hearing mothers supporting each other... they were the mothers of missing persons.

"Those guys were the detainees arrested by Assad's father in the 1980s. Some of them are still until this moment missing … there were no bodies, there was nothing, just silence."

Activism and arrests

Noura came up against the regime as an undergraduate at the University of Homs - and reading books such as George Orwell's Animal Farm chimed deeply with her own experience.

More from Global education

Ideas for the Global education series? Get in touch.

Noura's increasing activism, her work as a blogger, publishing imaginative allegorical fiction, and her readiness to speak out, led to two early arrests.

Nevertheless she continued this dangerous work, accessing forbidden websites to distribute anti-regime articles, disseminating ideas of democracy and non-violent protest.

"We never believed there would be a real revolution in our lifetimes," she said.

And then, in December 2010, the Arab Spring began in Tunisia, and spread rapidly, arriving in Syria with a demonstration in Damascus in March 2011.

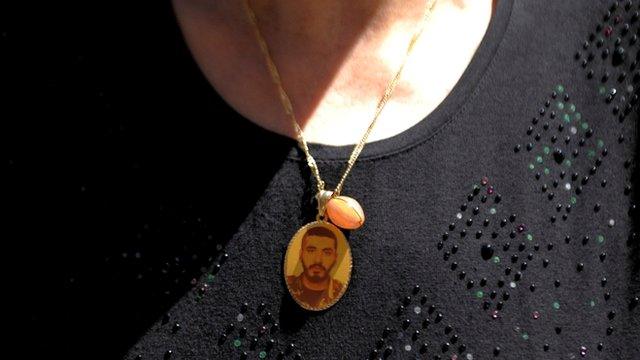

A mother in Homs with a locket of her lost son

"For me it was like a dream. We have a revolution." Noura was still in Homs, but was in touch with activists around the country, and abroad.

She became an organiser of demonstrations and an advocate for the rapidly rising numbers of detainees.

Social media

In the response that followed, many of her friends were killed, many others imprisoned and tortured.

"To be honest we were not shocked, we knew too well that this regime would not allow people to demand their rights."

They were more shocked, she said, by the lack of any effective response from the international community.

"We were saying, back in the 70s and 80s, when there were great massacres in Syria, there was no internet, there no media channels.

"But we thought, now we have the social media channels, hopefully this would protect us. But it did not protect us."

Noura's young life has been against a background of war: A fighter in Homs

Noura moved from city to city, organising, motivating, dodging the authorities - until in May 2012, she was ordered off a bus in Damascus by armed men and bundled into a car.

"It was not an arrest, it was abduction, a kidnapping," she said.

Tortured in prison

Noura emerged seven months later. During that time she was detained in some of Syria's most notorious prisons, and said she had been tortured with electric shocks and beatings.

She plays this down, saying that so many have endured - and are still enduring - far worse.

For her the hardest experience to bear was hearing the sounds of her fellow-prisoners being tortured. Her captors realised this psychological torture would be more effective in her case - but still she remained silent.

Noura explained how she survived: "I was not afraid for myself, I didn't care about myself... I cared only about the revolution… I cared about the people who were still continuing this revolution outside."

Homs this summer showing the damage of war

"We were still a non-violent movement on the ground... and I kept thinking about them... I wanted to make sure that in the questioning I would not speak about any one of those activists. I would pray to my body not to break down."

Noura was released late in 2012, and believes that an international campaign played a part in this: "For sure, all of those activities protected me. That is why we need this advocacy, all the time, for all detainees and for missing persons."

For Noura, the torment continued, as her younger sister, Alaa, had also been imprisoned and was suffering even worse: "They tortured her harder than me, many times, because of me."

Alaa was released in a terrible physical state; the family decided they had to leave Syria, and fled to Turkey to get urgent medical treatment.

"She was my only reason to leave Syria," said Noura. "Otherwise I would still be there."

Noura became a representative in peace talks in Geneva

In four years of exile in Turkey, she joined the coalition of Syrian opposition forces, (SNC) and became its vice-president in 2014, as well as being elected to sit on its negotiation panel in Geneva.

She joined because she realised this much-criticised group of mainly male, middle-aged "hotel revolutionaries" needed "the blood of youth" and also a strong female voice.

Geneva was a real challenge for Noura: "I felt I had to be calm and clever, I had do everything I could do, to interact."

She worked hard to get an agreement to break the two-year siege of Homs. Many of its surviving citizens were dying of starvation.

'Scholars at risk'

Noura resigned from the coalition in 2016, but continued working for an NGO she had created, Start Point, which provides advocacy and psychological support to Syrian women who have suffered torture and sexual violence in detention.

She had also met her husband in Turkey, another Syrian activist in exile, who was one of a network of cyber-security experts working for the Munk School's Citizen Lab; hence the Toronto connection.

Noura came to Canada as one of 24 international students with scholarships in the university's "scholars at risk" programme.

With her daughter due to be born next month, Noura is aware of how this might change her activism. But she's determined not to give up the fight.

She sees the master's degree as another step to help her continue her work to bring democracy to Syria.

"I feel also that being a mother makes me closer to the future... this baby is the future, and maybe will not have to live as our generation live."