UK interest rate decision looms

- Published

- comments

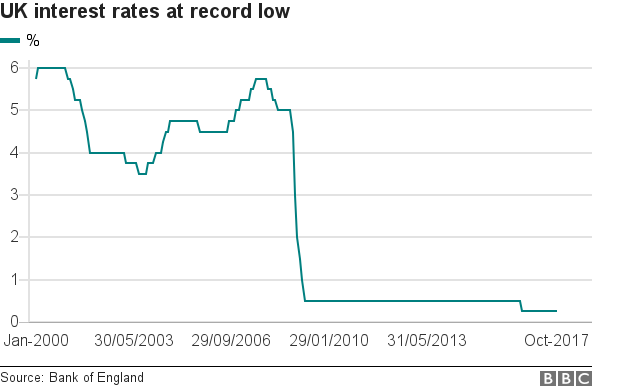

The Bank of England will deliver one of the most closely watched interest rate decisions since the financial crisis later on Thursday.

Economists and investors are expecting the first increase in a decade.

In September, the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) laid the groundwork for an increase "over the coming months" if economic growth remained stable.

If the Bank raises rates from the current 0.25%, it would represent the first increase since July 2007.

Commercial banks use the Bank of England's base rate as a reference point for their accounts and loans.

Higher rates are expected to hit the 3.7 million households with a standard variable rate (SVR) or tracker mortgage. However, they will also benefit a large share of the 45 million savers who are likely to enjoy higher returns from accounts that pay variable interest rates.

Charities and business groups have warned the Bank against raising rates, which they claim will put a strain on homeowners and companies struggling to make ends meet.

However, mortgage lender Nationwide has described the impact of a small rise in interest rates as "modest" for borrowers whose repayments are linked to the base rate.

Official data show more homeowners are fixing the interest rate charged on their mortgage than a decade ago.

The total share of new mortgages taken out on a fixed rate was just under 88% in the second quarter of 2017, according to the Bank of England. This compares with 46% at the start of 2008.

'Anaemic' growth

Financial markets believe there is more than a 90% chance that the Bank will increase rates to 0.5%, just over a year after reducing them to a new low of 0.25% in the wake of the Brexit vote.

Not all economists favour a rise though. Danny Blanchflower, a former member of the MPC and now economics professor at Dartmouth college in the US, said he saw "nothing" in the recent economic data to justify higher interest rates.

"We've seen an inflation jump due to a fall in the value of the pound. But that's a once-off jump that's going to drop off in the next few months. Real wages are falling. Retail sales are falling.

"Growth in the UK is anaemic at best," Prof Blanchflower said.

But Dame DeAnne Julius, also a former MPC member and chair of University College London, is "absolutely" in favour of a rate rise.

"Although I'm sure that the fall in sterling has been part of the story, it's certainly not the whole story," she said.

"The degree of slack in the economy... is down. Unemployment is at a 40-year low. Also the negative effects of having such low interest rates for such a long period of time are really showing up."

Where were you when interest rates last went up?

Solid growth

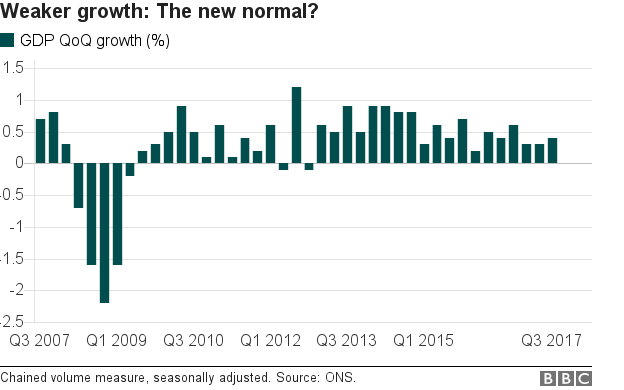

Official economic growth figures showed the UK economy expanded by 0.4% in the three months to the end of September compared with the previous quarter.

This is stronger than the 0.3% expansion expected by the Bank.

In September, the MPC said that a "majority" of members believed that some withdrawal of stimulus would be appropriate if the economy continues to grow at a steady pace.

A 0.4% increase in gross domestic product (GDP) may sound unspectacular. The average quarterly growth rate since 1993 has been about 0.6%.

But weaker investment and productivity means the economy and living standards may never grow at the same pace as seen before the financial crisis.

This means the Bank may have to raise rates to keep a lid on inflation, even if growth remains subdued.

As Bank of England governor Mark Carney put it: "The speed limit, if you will, of the economy has slowed."

In other words, this may be as good as it gets.

Prices have been rising faster than pay in recent months, and this has put pressure on UK households.

Inflation, as measured by the consumer prices index (CPI), stood at a five-year high of 3% in September.

This is also above the Bank's estimate of 2.8%. Policymakers believe inflation will peak just above 3% in the coming months.

Pay growth low

The UK's jobs-rich recovery has continued, with unemployment falling to a four-decade low of 4.3% in recent months.

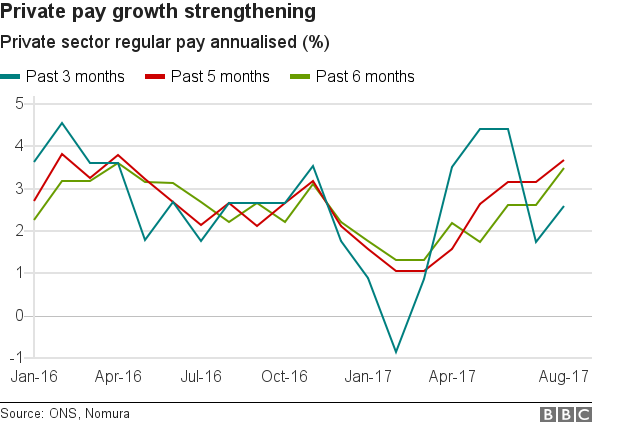

But pay growth has remained weak.

Average total weekly earnings grew by 2.2% in the three months to August compared with the same period a year earlier, while the Bank of England's agents noted in September that pay deals had "clustered around 2% to 3%".

In the decade before the financial crisis, earnings growth averaged 4.25%.

However, there are tentative signs that pay could be picking up, particularly for the 82% of workers in the private sector.

Whatever the Bank of England decides on Thursday, one thing is clear. Any rate rises will be "limited and gradual".

Uncertainties remain on the horizon.

The Bank's current forecasts are predicated on a smooth Brexit, and it is likely to stress that future changes to monetary policy are not on a pre-determined course and will be dependent on developments within the economy.

- Published2 August 2018