The firm that can 3D print human body parts

- Published

Swedish firm Cellink can print human ears and noses

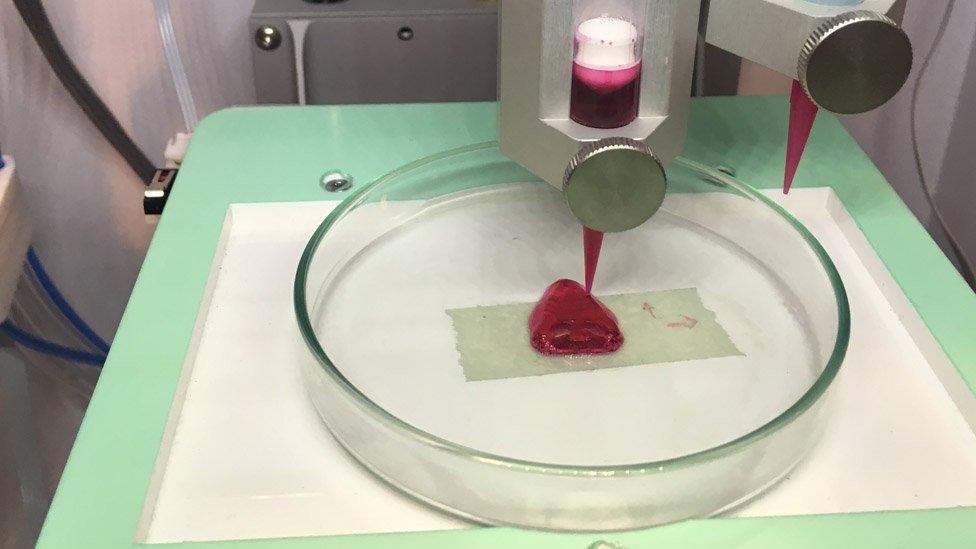

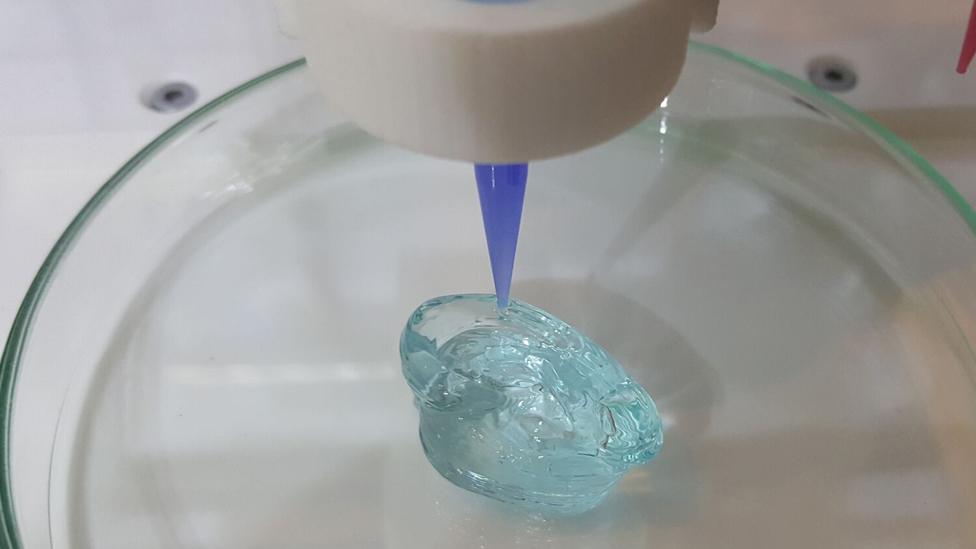

Erik Gatenholm grins widely as he presses the start button on a 3D printer, instructing it to print a life-size human nose.

It sparks a frenzied 30-minute burst of energy from the printer, as its thin metal needle buzzes around a Petri dish, distributing light blue ink in a carefully programmed order.

The process looks something like a hi-tech sewing machine weaving an emblem onto a garment.

But soon the pattern begins to rise and swell, and a nose, constructed using a bio-ink containing real human cells, grows upwards from the glass, glowing brightly under an ultraviolet light.

This is 3D bioprinting, and it's almost too obvious to point out that its potential reads like something from a science fiction novel.

Currently focused on growing cartilage and skin cells suitable for testing drugs and cosmetics, Erik, 28, believes that within 20 years it could be used to produce organs that are actually fit for human implantation.

Erik is the chief executive and co-founder of a small Swedish company called Cellink. Founded in Gothenburg only a year ago, it is a world leader in bioprinting, and Erik has big ambitions.

Erik Gatenholm (left) and co-founder Hector Martínez have very big ambitions for Cellink

"The goal [from the start] was to change the world of medicine - it was as simple as that," he says. "And our idea was to place our technology in every single lab around the world."

A former management student, Erik was first introduced to 3D bioprinters three years ago by his father Paul Gatenholm, a professor in chemistry and biopolymer technology at Chalmers University in Gothenburg.

The entrepreneurial Erik realised that there was a gap in the market for bio-ink, the liquid into which human cells can be mixed and then 3D printed. At Cellink this ink is made from cellulose sourced from Swedish forests, and alginate formed from seaweed in the Norwegian Sea.

Back in 2014, the bio-ink required to carry out cellular research by academics and pharmaceutical companies was typically mixed in-house by researchers and not available to buy online.

But Erik came up with a plan to market Chalmers University's bio-ink technology and become the first company in the world to sell standardised inks over the internet suitable for mixing with any cell type. He would sell these inks alongside affordable 3D printers.

The bio-ink is a liquid in which human cells can live

Erik's "lightbulb moment" was in 2015, and the following year, aged just 25, he co-founded the aptly-named Cellink with Hector Martinez, a tissue engineering student at Chambers.

Cellink quickly attracted numerous investors, and within 10 months of launching it had listed on First North, the Nasdaq stock exchange's market for emerging companies. The flotation valued the firm at $16.8m (£12.8m).

Achieving sales of $1.5m in its first year, it now has 30 employees and has opened three offices in the US in addition to its Swedish headquarters. It boasts customers in more than 40 countries.

"We said that we wanted to grow the company and from day one it was a global business," says Erik. "We understood that the customers are everywhere".

Cellink now has a second office in Boston, Massachusetts

With the bio-inks priced between $9 and $299, and the company's printers between $10,000 and $39,000, most of Cellink's sales have so far been to academic institutions in the US, Asia and Europe, including Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Harvard University and University College London.

But pharmaceutical firms are also increasingly using Cellink's technology to develop products, by conducting tests on bioprinted human tissues, potentially reducing the need for animal trials in the process.

The company puts its rapid global expansion down to a range of factors, including access to existing technologies already developed for standard 3D printers, a strong online presence through videos and social media, and plenty of traditional, face-to-face contact with clients.

"We go to the customer. We spend days there. We train them and ensure that they are up and running," says Erik. "It's the time that you spend with the customer where you truly learn what they need."

Some people have ethical concerns about bioprinting

Iris Ohrn, a life sciences investment advisor at Business Region Gothenburg, the state-funded company working to increase investment in the city, says that Erik's confident and friendly persona has helped Cellink to grow.

"When you meet Erik, you get the feeling 'this guy is going to succeed' no matter which company he starts," she says.

But taking risks, argues Ms Ohrn, was also an essential factor in Cellink's expansion.

She says that while bioprinting offers "incredible potential" when it comes to "drug testing, organ transportation and wound healing", the start-up took a gamble by launching its products before the human tissue market was fully developed.

The firm sells both the 3D printers and the bio-ink

Ms Ohrn adds that Cellink also correctly realised that it had quickly expand overseas quickly because "the Swedish market is very small".

"If you're going to succeed [as a Swedish firm] you need to go international very quick," she says.

Cellink's meteoric rise has, however, not been without its challenges or controversies.

Erik admits that his core team has needed to work hard to understand local laws and safety regulations, and to provide a 24-hour service for customers spread across the world.

"You've always got to be available," he says. "It doesn't matter what time it is at your location... you're carrying two or three phones just so you can comply with all the different time zones."

Erik hopes that the recent opening of its US headquarters in Boston will allow it to grow even further thanks to "employee spill-over" from major American pharmaceutical firms and universities.

"Being in that area, we have the ability to pick some of the most brilliant minds in the world," he says.

This is the fifth story in a new series called Connected Commerce, which every week highlights companies around the world that are successfully exporting, and trading beyond their home market.

Meanwhile Cellink is planning ahead to reach its much longer-term goal - to help solve a global shortfall in organs available for transplants.

Many experts in the field predict that bioprinting could be used to create functioning organs for implantation within 10 to 20 years, a possibility that opens up a minefield of ethical concerns that are set to keep the company on its toes as it continues to grow.

"A lot of people could think that bioprinting is 'playing God'," admits Erik.

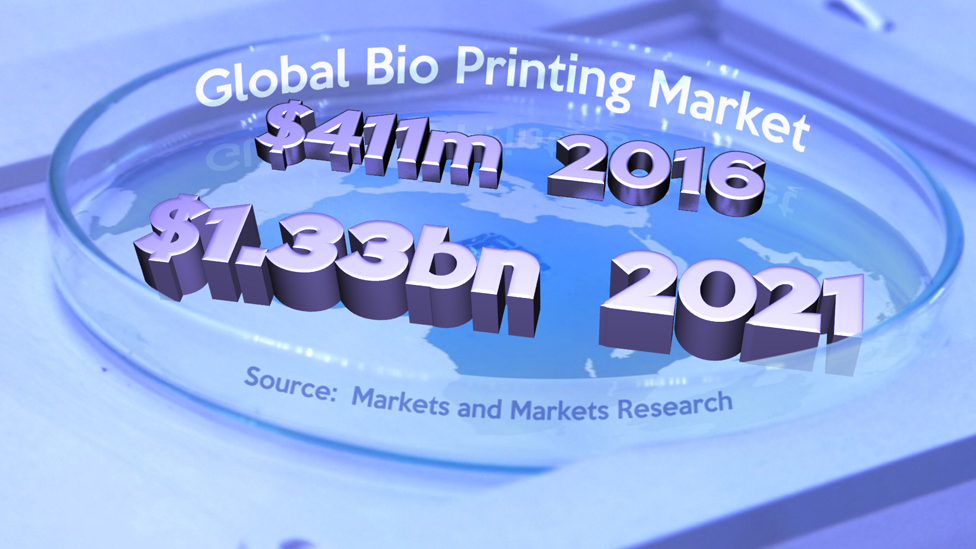

The global market for bioprinting is expected to expand greatly

But he argues that his firm is in favour of a climate that encourages scrutiny and regulation as the market evolves, and says that Cellink is already starting to work closely with relevant medical bodies and institutions.

He says that collaborating on safety tests and standards will ensure that the emerging bioprinting industry doesn't end up transforming its science fiction script into a horror movie.

"I believe in this. This is my passion. I live for this and I just don't see that any regrets are very vivid today," he says.