Paradise Papers: Are we taming offshore finance?

- Published

Like the Cheshire Cat, it's hard to tame something that keeps disappearing and reappearing

The offshore finance industry puts trillions of dollars worldwide beyond the taxman's reach. Bringing it to heel is like taming a cat; not just a normal moggy - a thankless task in itself - but a Cheshire Cat: nebulous, hard to pin down, disappearing and reappearing when it likes.

No-one can actually agree on what a tax haven is. Or even on the name: one person's tax haven is another's "offshore financial centre". No-one can agree on how many there are. Nor on exactly how much money is stashed offshore. No statistics are fully reliable.

And this suits those who operate in offshore finance, from the owner of the wealth to the lawyer or accountant middlemen who manage the funds, to the often sun-kissed beaches of the jurisdictions where they are secluded or pass through. The industry's key word is privacy. Or secrecy - a word it doesn't like so much.

One adage cited by the taxation author and expert Nicholas Shaxson sums it up: "Those who know don't talk. And those who talk don't know."

But do we really not know how much is stashed offshore?

A report this September, co-authored by the economist Gabriel Zucman, estimates about 10% of global GDP - the way we measure the size of the world's economy - is held offshore, about $7.8tn (£6tn), external. The Boston Consulting Group reported it last year at about $10tn.

If you are thinking, wow, that's bigger than Japan's economy, you'd be right. But if you want a real wow, try $36tn - the estimate offered by James Henry, author of the book Blood Bankers. That's twice as big as the US economy.

But no-one really knows.

And here's another wow. Remember the slogan "we are the 99%" coined by the Occupy movement to lambast the top 1% of the population for their disproportionate share of wealth? Well, the Zucman report says 80% of all offshore cash is owned by 0.1% of the richest households, with 50% held by the top 0.01%.

So if you read this and are thinking, if you can't beat them... quite frankly, it's unlikely you will ever join them. The management fees for the ordinary person will probably far outstrip the gains.

As Nicholas Shaxson told BBC Panorama: "At the very lowest end you'll have the middle classes doing little bits and pieces. But the large majority of what's going on, this is a game for rich people."

Legal, but ethical?

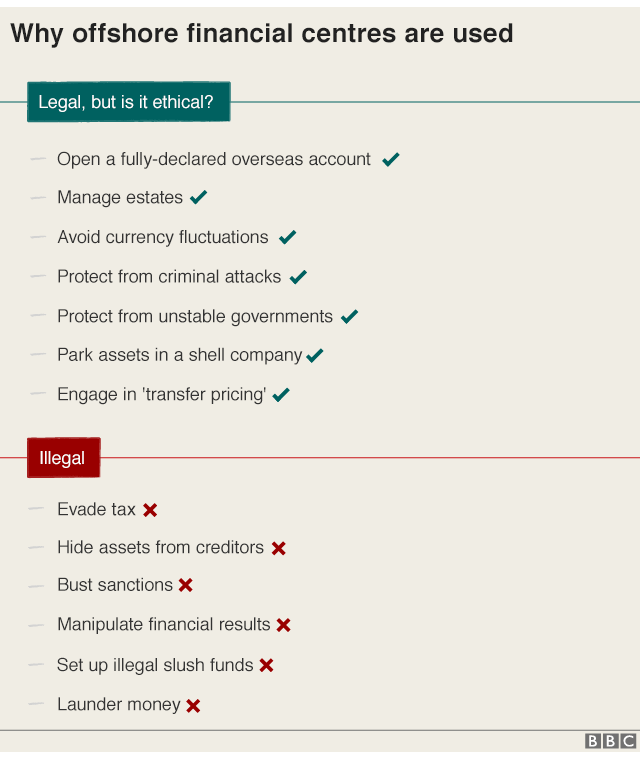

Surely we know some of how this works? The systems have a ring of familiarity - double taxation; tax inversion; trusts; shell companies etc. It's just we don't usually know who's in the schemes and what they are getting out of them.

The basic essence is rerouting money in one location where you don't like the taxation rules to another location - one that is stable and reliable - where there aren't as many, or any.

For example, if you want to protect your assets to stave off creditors, stick them in an offshore shell company. Hey presto, much harder to get at. Want to hide ownership of a property? Put it in a trust.

This is not illegal. There are many other schemes, legal, illegal and sometimes ethically debatable. But even within these categories there are many variables on what actually constitutes The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. After all, in the film with that name the ugly arguably wasn't as bad as the bad, and the good was hardly perfect.

True to their Cheshire Cat-like origins, offshore financial centres (OFCs) do not always appear where one might expect them.

That's because offshore, sorry to confuse you, is also onshore. This makes it impossible to pin down the global number of OFCs. It could be 50, 70 or more and new ones come and go.

The US and UK are arguably two of the biggest OFCs.

For example, setting up shell firms is easy in some US states, like Delaware.

And it's widely known that the City of London acts as the facilitating hub for Crown dependencies and overseas territories that channel trillions of offshore dollars.

The smaller, often island, nations are what Nicholas Shaxson calls "captured states".

Investigative journalist Nicholas Shaxson on why tax havens are ‘like captured states’

He told Panorama: "These places don't have a very deep pool of experienced people. They're just people who say, well we trust the accountants, we trust the lawyers to tell us what's best for our island and we'll do it."

So how does offshore defend itself?

Well, the jurisdictions say it's wrong to think there are banks in OFCs sitting on pots of gold - the money is simply being reinvested by companies - and that if there were no OFCs there would be no constraint on the tax rates governments might levy.

OFCs, they say, simply pump cash around the globe and the new transparency rules put in place over the past decade have severely limited tax evasion.

It's certainly wrong to lump all the OFCs together. Some are better regulated than others. Down at the murkier end, dealings in Panama were exposed by leaks last year.

But Bermuda's Bob Richards offered a stout defence of its financial services in an interview with Panorama carried out while he was still finance minister, citing a taxation system that had been in place for more than 100 years and adding that if other nations were losing out on tax they should sort their own systems out.

Bermuda, he says, has fully signed up to an international agreement that allows for the automatic transfer of tax information within governments and such a jurisdiction "cannot be a tax haven".

And Appleby, the financial services firm involved in these latest leaks, made the case for OFCs back in 2009, in the wake of the global crash.

Ex-Bermuda Finance Minister defends tax practices

It said there was "no evidence OFCs played any role in the economic crisis", external, OFCs were "neither the source of - nor the destination for - criminal proceeds" and that OFCs "protect people victimised by crime, corruption, or persecution by shielding them from venal governments".

Of the latest leaks, the company said: "Many of the questions raise matters where - on any view - there is plainly no conceivable wrongdoing on the part of Appleby whatsoever."

OFCs say there are no secrets, just privacy. But Gerard Ryle, of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, which oversaw this huge leak of financial documents, known as the Paradise Papers, dismisses this.

"The only product that the offshore world sells is secrecy and when you take away secrecy they don't have a product anymore," he told the BBC.

"Where you have secrecy, you have the potential for wrongdoing."

Whatever term you prefer, the elusive nature of offshore makes it hard to root out wrongdoing.

You could start an investigation into one firm or individual and be shuttled around from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, company to company, turning up a whole tranche of names on documents that are linked to no real owner, sometimes no real person, and lead absolutely nowhere.

A vicious circle

You're probably also thinking, we've now had an awful lot of these financial leaks, haven't they changed anything?

Spin backwards to April 2016. The Panama Papers have just come out. Iceland's PM Sigmundur Gunnlaugsson has resigned after the leaks showed he owned an offshore company with his wife.

Thousands are demonstrating in Reykjavik to vent anger at their politicians.

Some estimates put the protest numbers at 6% of the whole Icelandic population. That's like if 19 million people turned up to a protest in the US today.

But then travel over to Elektrostal, two hours east of Moscow. Resident Nadezhda is haranguing BBC reporter Steve Rosenberg. "All these 'investigations' are a waste of time and money. We know what you're up to. They're trying to rub Putin's face in the dirt," she says.

It kind of depends on where you are.

Ragnar Hansson at the Iceland protest

In the West, at least, people are questioning what high-net-worth individuals and multinationals can get away with.

Is it right that they can use loopholes to keep more of their cash? Or should it go to governments to spend on their people?

To be fair, governments have been tracking stashed cash since the 2008 global meltdown, independent of any financial leaks, although their talk has usually been tougher than their action.

Secrecy is now harder to achieve, transparency is greater. So-called country-by-country reporting, requiring multinationals to break down how they operate in different nations, external, has widened and public registries of companies have increased.

Even Russia brought in a law requiring the disclosure of offshore assets. The result? Since the law came in three years ago, dozens of the super-rich have given up Russian residency to avoid it. , external

There are also OFC blacklists mooted but, as Nicholas Shaxson says, the big players will make sure their operations are not on it and it will weed out only the minnows.

The offshore firms will "recalibrate", he says. "When legislation changes, you will have this ecosystem kind of readjusting and the money will shift to other places."

And wealth holders will readjust too. Pump cash into diamonds and artworks maybe? Or just go and actually live somewhere that charges low tax.

What makes this a vicious circle is that many governments are fully prepared to sanction offshore finance. Indeed, many people in government use it, as these leaks show.

And there is one thing we do know. If the super wealthy don't pay the taxes, the money has to come from everyone else.

Which to many may sound a bit mad, but as the Cheshire Cat says: "We're all mad here".

The papers are a huge batch of leaked documents mostly from offshore law firm Appleby, along with corporate registries in 19 tax jurisdictions, which reveal the financial dealings of politicians, celebrities, corporate giants and business leaders.

The 13.4 million records were passed to German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung, external and then shared with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, external (ICIJ). Panorama has led research for the BBC as part of a global investigation involving nearly 100 other media organisations, including the Guardian, external, in 67 countries. The BBC does not know the identity of the source.

Paradise Papers: Full coverage, external; follow reaction on Twitter using #ParadisePapers; in the BBC News app, follow the tag "Paradise Papers"

Watch Panorama on the BBC iPlayer (UK viewers only)