How a speedy emergency services app is saving lives

- Published

How an emergency services app is helping to save lives

Many of us assume that if you call an emergency number like 911, 999 or 112, someone will answer quickly and help will arrive soon wherever we are in the world.

But across Africa, this isn't always the case.

In Kenya's capital Nairobi, for example, there are more than 50 different numbers for emergency services. Ringing round trying to find an available crew can be a lengthy - and potentially life-jeopardising - process.

You can wait two or three hours for an ambulance to arrive.

"You just take for granted that 911 [the US emergency services number] exists, and we did as well," says Caitlin Dolkart.

She and her business partner Maria Rabinovich had both been working in the health industry in Nairobi for years before starting their company Flare.

"We thought - what would we do in an emergency? So we started asking people to spot ambulances and realised there were so many around and no one has any idea where they are," says Ms Dolkart.

Flare co-founder Maria Rabinovich wants to improve emergency service response times

The pair created an Uber-style online platform that aims to connect people to the closest emergency responders.

Private ambulance crews log in to the system at the start of a shift. Their locations can then be tracked and monitored by any hospital registered to Flare.

"Within the system we have different ambulance companies, so depending on the resources we work together," says Patrick Kinyenje, who works as emergency co-ordinator or dispatcher at Care Hospital in Nairobi.

Flare aggregates all the available ambulances on a map so dispatchers like Patrick can choose the most appropriate vehicle based on where it is, the expertise of the crew, and the equipment on board.

It also incorporates Google maps traffic data to help emergency workers navigate the city's notorious traffic jams.

"The response time that we have seen has gone down from 162 minutes, which is the average, to about 15 to 20 minutes," says Ms Dolkart.

Firefighters in Nairobi often have to tackle major traffic jams before tackling major fires

Hospitals pay a subscription fee to access the service whilst individuals in the capital can sign up for membership, with levels of cover starting from around $15 a year.

The website promises access to a 24/7 hotline of emergency professionals.

"The membership product is like your emergency and healthcare concierge," says Ms Rabinovich.

The service is similar to ones run by Red Cross Kenya, Amber Health in India and Murgency in Dubai.

But will this business model really work in a country where $15 is three months salary for many people in the slums, according to Dr Stellah Bosire-Otieno of the Kenya Medical Association.

"By principle it's an excellent idea. But the target population that can afford it are the middle income earners who most likely have health insurance.

"Those in the low social economic regions wouldn't be able to afford this," she says.

In 2013, the government re-introduced a 999 emergency hotline number for the capital but it was inundated with prank calls and is now rarely answered.

During the recent election violence, the BBC rang the number a few times but didn't get through. On one occasion, someone did pick up the phone, though hung up immediately.

"To be honest it rarely works," explains Bethuel Aliwa, who runs ICT Fire and Rescue, a training school and Fire service.

"Also, the technology of 999 has not changed, people have moved to mobile phone, but I believe 999 is still on analogue, so it is quite a problem," says Mr Aliwa.

A 999 call goes direct to the police who then start looking for the nearest ambulance or fire engine. But there are dozens of numbers for the various emergency services, and often phone numbers belong to individuals rather than agencies.

There are many different ambulance services competing for business

"By the time a fire service arrives, it's often too late," says Mr Aliwa.

Flare is now working on aggregating private fire agencies onto the system.

Due to the nature of Nairobi's roads and the constant traffic jams, the crew at ICT have found that sending smaller fire trucks works better. The downside is they can carry less water.

In addition, being a private agency, the places they can get water from are limited.

More Technology of Business

"Within five minutes the water is done, we need to rush to the nearest hydrant. You are gambling, you know, today you'll either get water or not," says Mr Aliwa.

To solve this issue, Flare is mapping all the available water hydrants in the city and recording them on the platform. So in addition to available fire trucks, dispatchers can also identify the closest water points.

"When we first started to do the research on fire in Nairobi, we found there are up to 4,000 fire hydrants that are potentially working," explains Ms Rabinovich.

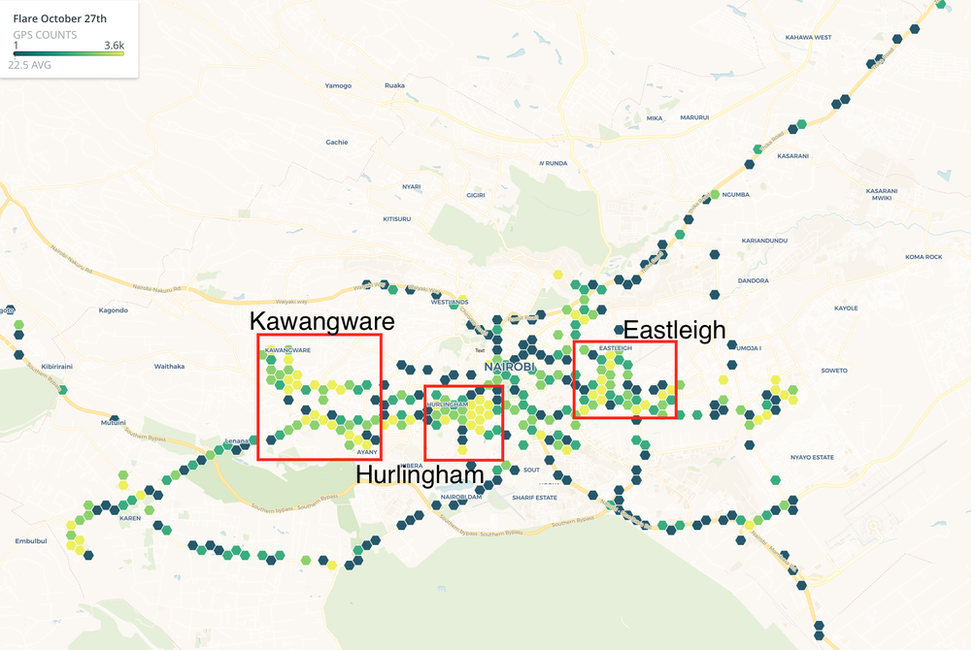

During the Kenyan elections in October, Flare recorded a 33% increase in ambulance movements

"But a lot of them are not in service. There are about eight that the firefighters currently use and know about, so there is a huge potential to improve fire response."

Flare is currently working with the private sector with the intention of adding more "concierge-style" features for members, such as real-time updates and treatment information.

The start-up is also collecting some interesting data.

"We learned there is a lack of ambulances between 7am and 9am because of shift handovers," explains Ms Dolkart.

"We're trying to encourage operators to stagger shift changes and make sure there is always an ambulance available," she says.

Flare hopes the information they are collecting for both the fire and ambulance service will prove useful in coordinating better services across the city.

Follow Technology of Business editor Matthew Wall on Twitter, external and Facebook, external