Budget 2017: UK growth forecast cut sharply

- Published

- comments

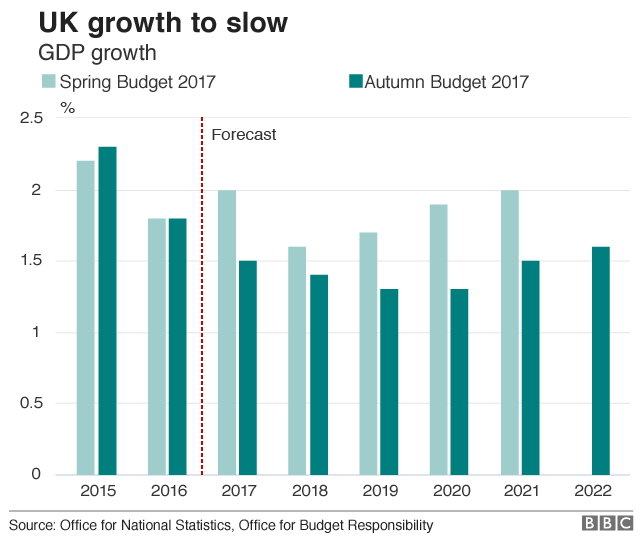

Growth forecasts for the UK economy have been cut sharply following changes to estimates of productivity and business investment.

The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) now expects the economy to grow by 1.5% this year, down from the estimate of 2% it made in March.

Growth, it says, will drop to 1.3% by 2020 and then rise to 1.5% in 2021.

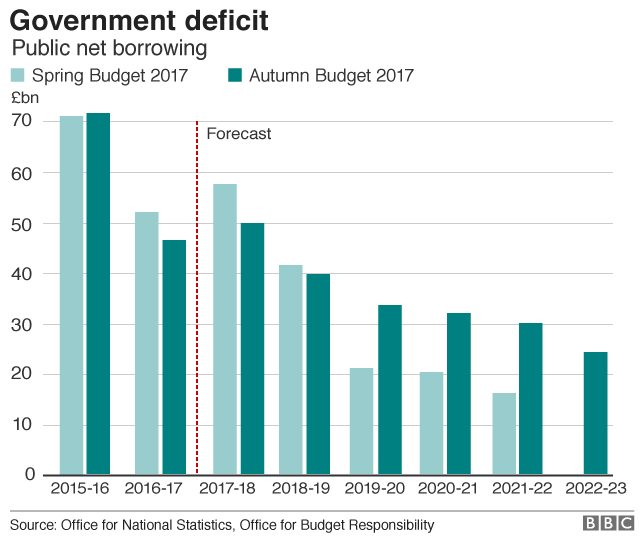

The lower growth means that by 2021-22 government tax receipts will be £20bn lower than the OBR's March forecast.

The OBR expects borrowing as a share of economic output will still fall, but not as fast as it predicted in March.

It forecasts that borrowing this year will be 2.4% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP), rather than its previous prediction of 2.9%.

By 2021-22, it says that percentage will be down to 1.3%. However, in March, it had expected borrowing to have fallen to 0.7% of GDP by then.

The figures make it harder for the Chancellor, Philip Hammond, to hit his target of bringing borrowing down to less than 2% of GDP by 2020-21. In March, the OBR estimated borrowing would then be at 0.9% of GDP. Today's forecast is for it to be at 1.5%.

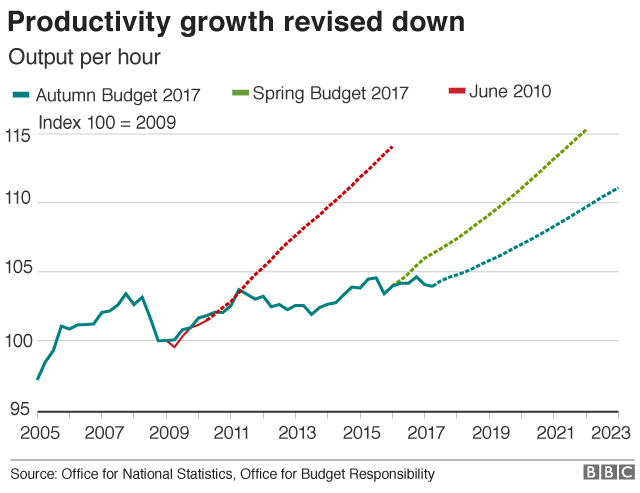

In his Budget speech, Mr Hammond said: "Regrettably our productivity performance continues to disappoint. Today the OBR revised down the outlook for productivity growth, business investment and GDP growth."

Yael Selfin, chief economist at KPMG UK, said: "The downgrade to UK GDP growth forecasts has totally overshadowed the generally good news on public finances so far this fiscal year, reducing the money available to the chancellor.

"However, the chancellor is sticking to his target of reducing public borrowing to less than 2% of national income by 2020-21, albeit with a reduced chest for any emergency spending in the event the economy requires an additional boost."

John Hawksworth, chief economist at PwC, said: "The headroom he used to have between his target and the forecast represented about £20-26bn. That's now been reduced to about £15bn because of less growth and more borrowing.

"He is trying to walk a tightrope of fiscal prudence and austerity."

The OBR says in its Economic and Fiscal Outlook report, external that the impact of lower productivity means that GDP will grow by 5.7% over the next five years rather than by the 7.5% as it estimated in March.

It added: "We expect real GDP growth to slow from 1.5% this year to 1.4% in 2018 and 1.3% in 2019, as public spending cuts intensify and Brexit-related uncertainty continues to bear down on activity."

However, it said that the revisions to productivity had nothing to do with Brexit, or with the latest economic figures, but simply because of what it called a "repeated tendency throughout the post-crisis period for productivity growth to disappoint".

Ian Stewart, chief economist at Deloitte, said: "The OBR's view that weak productivity is here to stay, and is not just a lingering hangover from the financial crisis, means a longer haul to eliminate the deficit and slower wage growth."

The OBR has also cut its estimates for business investment. Its report said: "We now expect business investment to rise by around 12% between the first quarter of 2017 and the first quarter of 2022, significantly lower than the 19% expected in March.

"This downward revision reflects the weaker outlook for productivity growth lowering the expected return on capital."

On unemployment, the OBR said it believed the rate was now as low as it is going to go.

"We expect the rate to trough at 4.3% of the labour force - its current rate - in the second half of this year, and then to edge up as GDP growth slows a little further and the National Living Wage prices some workers out of employment."

- Published22 November 2017

- Published22 November 2017

- Published22 November 2017