Bug eat bug - controlling pests with other insects

- Published

The Brazilian firm that breeds wasps that are released over crops to control pest insects

It is not a job for someone who is scared of creepy crawlies.

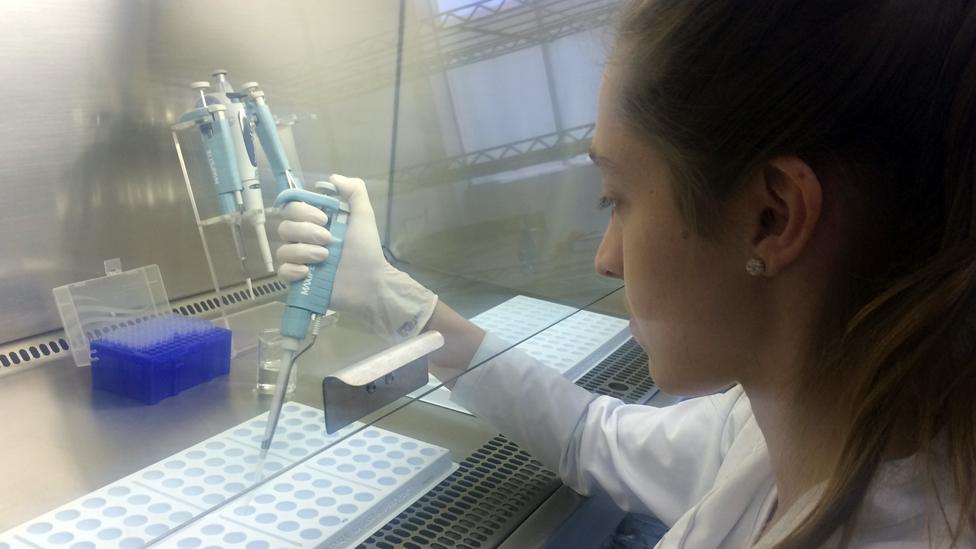

The team of laboratory workers are busy collecting the eggs laid by thousands of bugs in large plastic containers.

They have to shake and brush away the insects, which scurry quickly to and fro over their hands.

The employees can then remove strips of fabric from the containers, and scrape off the attached eggs.

This is the itchy scene at a hi-tech Brazilian company called Bug Agentes Biologicos, or Bug for short.

Bug is able to breed insects in big numbers

The company is at the forefront of the growing global biological pest control industry - it produces bugs that kill other creepy crawlies, thereby removing the need for chemical pesticides.

Fuelled by growing demand from Brazil's vast agricultural sector, Bug has developed a way to mass produce a tiny wasp called trichogramma that eats caterpillars and other pest insects.

Brazilian farmers then use drones to spray the wasps over their fields.

Bug was set up in Sao Paulo state back in 2000 by Brazilian scientists Diogo Rodrigues Carvalho and Heraldo Negri de Oliveira.

Heraldo Negri de Oliveira (left) and Diogo Rodrigues Carvalho wanted to help reduce the use of chemical pesticides

They wanted to help Brazilian farmers reduce their use of pesticides on crops - but never thought they would be good at running a business.

Mr Carvalho says: "Farmers used to just use chemicals to combat pests, and a lot of these chemicals were used in excess. This is bad for the environment and the people who work in the fields.

"Biological control using insects to control pests cuts pesticide use and brings more equilibrium to the countryside."

Yet despite the two friends' big ambitions, the firm didn't make any profits in its first eight years. It was only kept in business thanks to research and development funding from the Brazilian government, and private investors.

The wasps are spread over crops using drones

The big breakthrough came in 2008 when it started to breed thousands of wasps in each batch, which turned the start-up into a business that has grown by an average 30% each year ever since.

Mr Negri de Oliveira says that back in the firm's early days they couldn't simply call someone for advice, or order in the equipment they needed, because what they were doing was so new.

"Setting up a biological pest control company 17 years ago was not an easy thing to do," he says.

"Whey you set up a pizza shop, you go to a supplier, and you buy everything you need to make pizzas.

Bug is an expert at breeding the trichogramma wasp

"When you start a biological pest control company there is nothing on the market that helps you set it up. Everything we have here today is either something we adapted from another industry, or developed ourselves."

Despite the company's slow start, Bug's ambition from day one was to try to produce bio-pests on a grand scale.

Mr Negri de Oliveira says: "When we set up our business, people would say 'you will work with greenhouses or family-sized properties?'.

"And we would say 'no, we will work in great [big] fields'. And we are going head-to-head with agrochemical producers.

"Our company's greatest achievement was to find a way to use this solution in big, open fields."

This is the seventh story in a series called Connected Commerce, which every week highlights companies around the world that are successfully exporting, and trading beyond their home market.

Bug's expertise has caught the attention of agricultural companies around the world, and at times its exports have accounted for 15% of its annual revenues.

However, selling overseas has not been entirely straightforward.

Firstly it has never been able to export its wasps, due to fears over invasive species. Instead it has exported the other part of its specialism - the insect eggs that the tiny wasps first attack by laying their own eggs inside.

Working for Bug can be a dusty business

Bug has the technology and skills to produce vast quantities of these eggs, which are then sterilised ahead of export so that they can't hatch.

From 2004 to 2012 Bug exported these eggs to laboratories around the world, so that other bio-pest researchers and companies could more easily breed their own wasps.

Bug says it did not have to seek its overseas customers. Instead, they were attracted by positive word-of-mouth and coverage at international conferences.

The company now has 65 employees

By 2012 it had exported the insect eggs to 16 countries, including the US, Canada, Spain, Italy, Germany and Israel.

But that year Bug had to suddenly stop its export trade when strikes by Brazilian customs officers meant that export shipments of the highly perishable eggs could not be flown out of the country on time, and so had to be destroyed.

Bug and similar companies are reducing agriculture's reliance on chemical pesticides

As strikes continued over subsequent years, it is only now that Bug and its 65 employees are starting to export again, with 2kg or $10,000 (£7,500) worth of eggs going to Canada before the end of 2017.

Dave Chandler, a microbiologist and entomologist, at the UK's University of Warwick, says that Bug will continue to benefit from the increasing global demand for biological pest control.

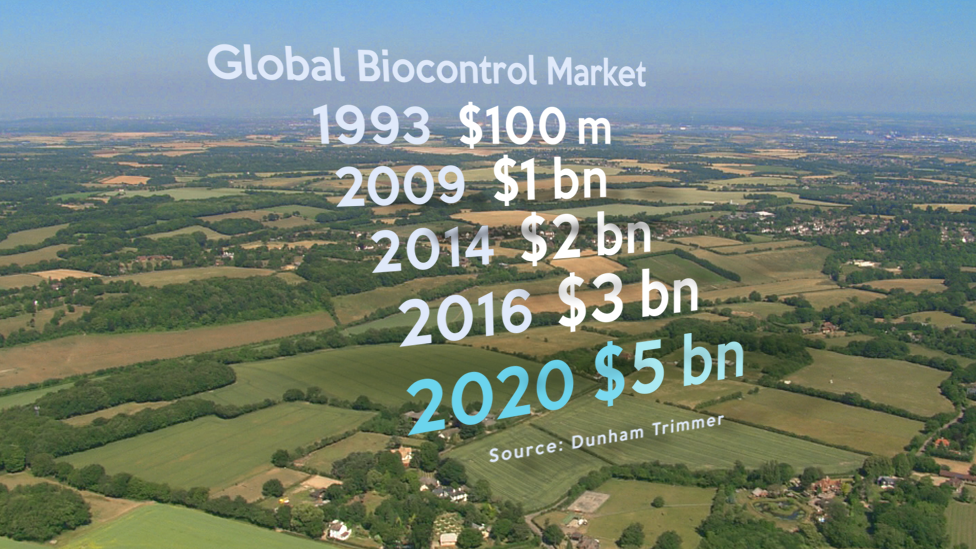

This is borne out by a 2016 report which said that the bio-pest sector is due to grow to $5bn a year by 2020, external, up from $3bn last year.

The global bio-pest marketplace is expected to expand strongly

Mr Chandler says: "So farmers and growers need alternatives to chemical pesticides, because of the evolution of resistance to chemicals, and governments are demanding more environmental forms of crop protection.

"So there is money to be made from it, both for large companies, and also for small suppliers as well."

Mr Negri de Oliveira adds that using biological control to combat pests is "here to stay, there is no going back".