How to keep a family business running after 200 years

- Published

Two generations of the Loane family - from left, Bryan Loane, Morgan Loane and Scott Loane

The rumours that swirled around the American east coast city of Baltimore in 1895 were grossly inaccurate. The word on the street was that the Loane family business had shut.

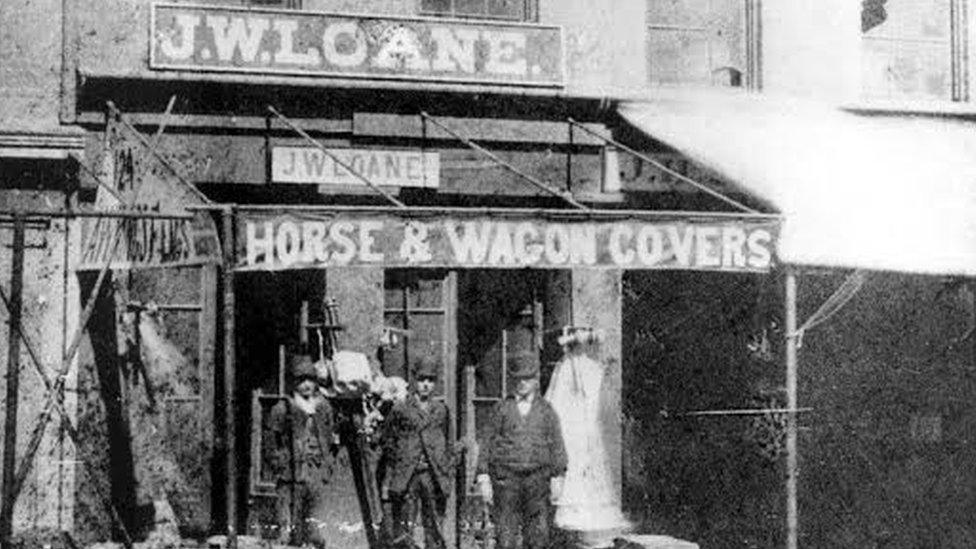

So Javez Loane, who at the time ran the business that made sails, window awnings, tents, flags and wagon covers, distributed a flyer to set the record straight.

It said: "No, old man JW Loane... has not gone out of business, however much some people may think so."

Taking a jab at the source of the false rumour, probably a competitor, it added: "However much more some other people may say so."

The family business was instead thriving back then, and is still in fine fettle today, now known as Loane Bros.

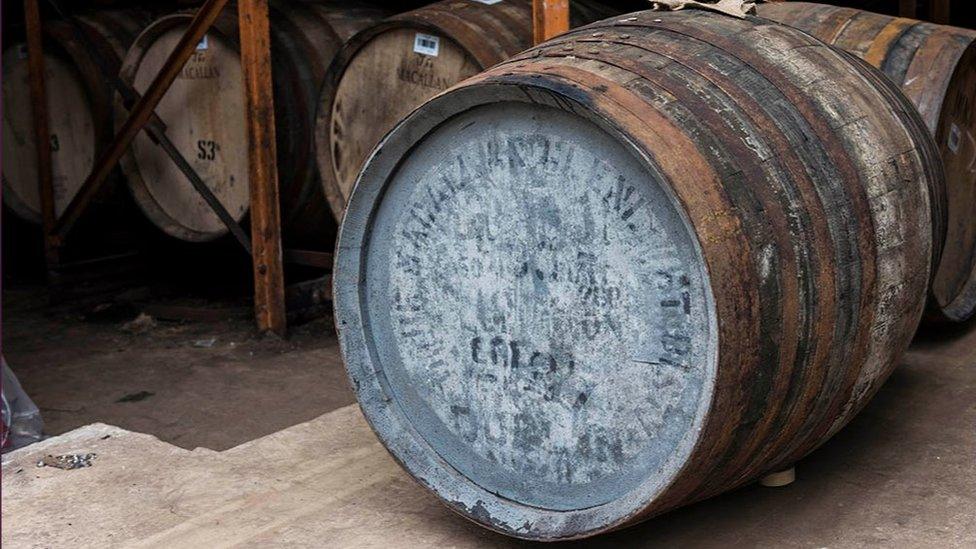

Loane Bros dates back to 1815

It's not a bad achievement for an enterprise that started by making ships' sails in 1815, and over the next 202 years moved to its current focus on party tents, equipment and window awnings.

With a Loane at the helm, the business has survived six generations of family ownership.

The word "survive" can be appropriate for any such business, given the added burdens that working with relatives can bring, such as exactly which nephew should inherit the hot seat.

In fact, only about 3% of family firms make it to the fourth-generation and beyond, according to publication the Family Business Review.

"I think we've had a lot of luck in many ways," says Bryan Loane, 55, the firm's current president. "When one industry died down, we were able to add another one."

The business went from selling sails to hiring out tents

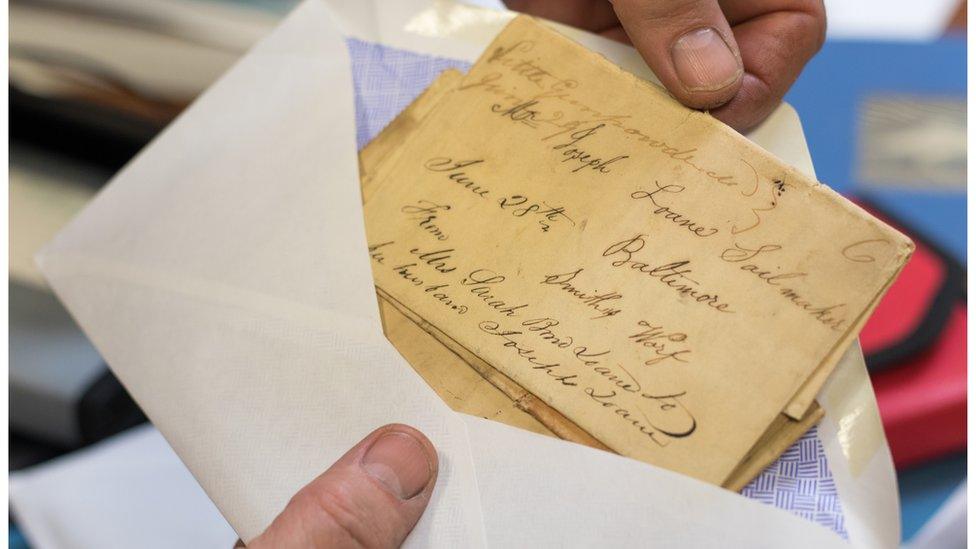

Bryan owes his vocation of 30 years to Joseph Loane, a sail maker from Portsmouth, England, who took his trade to Baltimore in 1815.

Joseph couldn't have picked a better place to establish himself in the US.

Baltimore had a deep harbour that provided plenty of ships in need of fresh sails. And as the east coast's most westerly harbour, it was also a launching point for many heading inland, hence the trade in wagon covers.

As son took over from father and steam took over sail, sail-making was virtually gone by the start of the 20th Century. But then awnings as a primary source of cooling during the stuffy Baltimore summers became all the range.

As air conditioning came in - shrinking the awnings division of the business in the lead-up to the 1950s - tent-making and tent rentals became the primary revenue stream.

Fast forward to today, and the company has about 85 employees and a yearly income of about $5m (£3.7m).

Workers wash white tents after an event

In addition to hiring out tents for everything from wedding receptions to conferences, it hires a host of other things required for a big bash, from tables and chairs, to wine glasses, plate sets and even a dance floor.

"We are still always learning to improve on what we do and how we do it," says Bryan, who initially went to college to study teaching.

He studied teaching in order to gain insight into a different profession, as he knew he would have to enter the family business at some point.

When he was about 24 and teaching in Spain, Bryan got a call from his father Morgan who announced he was thinking of selling the business.

Within weeks, Bryan came back and started work under his father. About 20 years ago, Morgan retired and Bryan took over.

"It's sad to say, but I enjoyed it a lot more after he left," says Bryan.

Bryan says it gave him a chance to put his own stamp on the family business, just like his father had done when he became boss.

Morgan still helps out occasionally by sitting in on a sales call, or driving his son to meetings in nearby Washington DC, so that Bryan can get work done in the passenger seat.

"I found out I was the fifth wheel when I came around," jokes Morgan.

The firm's hopes for the future may involve staff buying the business

He intentionally made a clean cut from running the business when he retired. Instead he left it to Bryan, assisted by Bryan's brother Scott.

"Succession of generations is not easy because you are phasing someone out," adds Morgan. "I'm delighted with what they have done with it."

"It is truly an accomplishment to have a business for five or six generations," says Barbara Spector, the editor-in-chief and associate publisher of Family Business Magazine.

One of many issues a family firm can face, is a tendency to tread lightly around change because a succeeding family member might not want to offend the older generation.

But you have to adapt or die, says Ms Spector. "The family legacy is entrepreneurship rather than doing one particular thing that may or may not be in demand over time."

Ms Spector says that family businesses can sometimes become vulnerable after the third or fourth generation.

By then distant cousins might not know each other so well; they might not live in the same city or country - nor share many values on how a firm should be run.

Pruning the family tree, where one branch buys out the other branches can "certainly make things easier," she says.

A letter addressed to the firm's founder, Joseph Loane

Whether Loane Bros will continue with family ownership over the next generation is uncertain. Bryan's two children have interests elsewhere, and he is careful not to put pressure on them to come into the firm.

"I would be amazed if my son or daughter came into the business," he says. "We will cross that bridge later, but I'm not planning on it."

Loane Bros is constantly approached by investors wanting to purchase it. but Bryan says he has seen other family businesses go down that road and it isn't good.

"The whole company just vanishes after a while," he says. "They say they will keep all the people on, but they don't."

Many employees at Loane Bros have worked there for decades. They might be the ones Bryan chooses to sell the business to, so it becomes employee-owned.

"They have dedicated their lives to it," he says.

If no one in the family wants to take it over, Bryan sees selling it to its staff as the best way to preserve the legacy Joseph Loane started all those years ago.

"I'm sure [Joseph] never thought we would still be here doing this."

- Published20 November 2017

- Published31 October 2017