The issue threatening to derail Brexit

- Published

A mock customs post on the Irish border was part of a Brexit protest earlier this year

The last time I was on the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, a garage owner bet me I would cross it without noticing. He won.

But now the UK is leaving the EU, all that could change and the border has become one of the toughest and most controversial parts of the Brexit negotiations, because:

The Republic of Ireland will not accept an open border with Northern Ireland if it means it has to introduce a border between itself and the rest of the EU

Northern Ireland and the UK government will not accept a border between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK - they remain after all a single country

Northern Ireland and the Republic do not want a "hard" border between them on any account; they remain after all committed to the peace process.

This is both a political and economic issue: 30% of Northern Ireland's exports go to the Republic, and a third of that is food and animal exports.

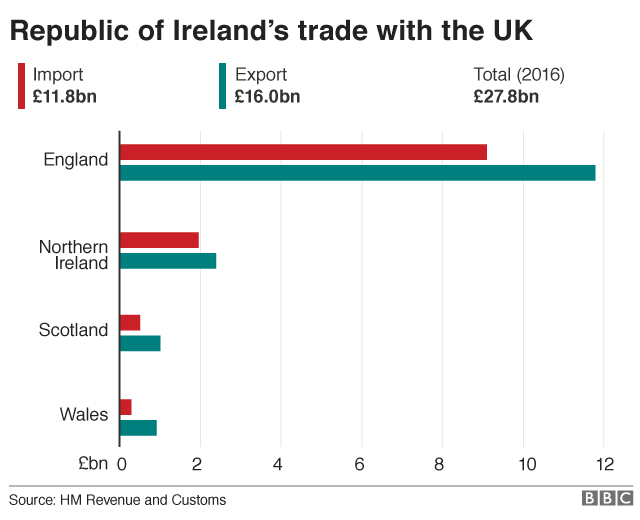

In total, 55% of Northern Ireland's exports go to the EU, including the Republic. In the opposite direction, 13% of the Republic's exports go to the UK, its second-largest market after the US.

An invisible and frictionless border?

Arlene Foster is leader of the DUP, which props up Theresa May's government

The solution proposed on Monday to keep the border open and that trade flowing, called for "regulatory alignment"; a choice of words that is almost as opaque as the border.

It means (or could mean) that similar rules and regulations would continue on both sides of the Irish border, so trade could proceed unimpeded. Yet even this compromise probably could not ensure an invisible border.

Norway is in the Single Market, is a member of Schengen (allowing free movement of citizens between countries), but is not in the EU's Customs Union. Its land border with the EU is fairly open, but still has checkpoints.

That is a moot point for the moment, as yesterday the compromise was vetoed by the DUP, the largest Unionist party in Northern Ireland. The DUP is worried that "regulatory alignment" means different laws in NI from the rest of the UK. For them this is totally unacceptable, but the consequences go much wider and further.

Already Wales, Scotland and London have jumped on that band wagon and called to be included in "regulatory alignment", to protect their economies from what they see as the expected shocks of Brexit.

No country can have a jigsaw of different rules and laws applied town by town or street by street. So the obvious answer is that if there is "regulatory alignment" between NI and Ireland, surely it must also exist between all of the UK and the EU?

Not really Brexit?

However, if the UK follows the same rules and regulations as the rest of the EU, have we really left it at all? For a start, negotiating free trade deals with the rest of the world is going to be difficult. What would it have to offer if it was sticking so close to the EU?

If the EU insists the UK sticks to its food standards, chemical regulations, car safety rules and all the rest, then what are the economic benefits of leaving? For many Brexiteers the whole point was to cut the UK free from EU "red tape" and become a free trade and free market economy, trading with the rest of the world. "Regulatory alignment" might strangle many of those hopes at birth.

Another model being promoted by No 10 might be to limit "regulatory alignment" to those areas necessary to support the Good Friday Agreement, which includes provisions for co-operation on matters such as agriculture, waterways and energy.

There is already one electricity market on the island of Ireland, but it is hard to see how coordinating agricultural policy would not clash with the fact that Northern Ireland will be outside the EU's Common Agriculture Policy, and Ireland inside it.

Out into the world?

The UK could cut its external tariffs to encourage trade, but what would stop those imports into the UK flowing into the EU via Northern Ireland? What if the UK allows in cheap American chicken that has been washed in chlorine, which is not accepted in the EU, or cuts all tariffs on cars - would they disappear over the border into the single market? Certainly the opportunities for smuggling and crime across that border would be huge.

Then there is the Common Agricultural Policy. Every farmer in the EU gets the same subsidies and applies the same standards and the EU protects its agricultural sector with common external tariffs and quotas on, for example, New Zealand lamb or Australian sugar.

If the UK and especially NI change standards in agri-chemicals or allow in more imports from the rest of the world at low or zero tariffs, it could all flow across the border into Ireland and the rest of the EU. The EU will not stand for undercutting EU farmers, making a mockery of common external tariffs and undermining the CAP.

One suggested solution is that technology will deal with this problem and we should all stop worrying. Checking goods at the factory gate rather than at the border, number plate recognition, larger companies regulating themselves and a dozen other ideas will all coalesce to create a seamless border that is invisible on the ground.

Any minor matters like organised fuel smuggling can be dealt with by local police and will anyway be a minor inconvenience. But it is far from clear that the Republic and the rest of the EU will believe this is enough to guarantee their external border, even if it works seamlessly.

Also if, as many Brexiteers want, we leave the EU and just depend on the World Trade Organisation rules the UK would have a problem. The WTO allows any of its members to cut tariffs to an agreed maximum or lower, but only if they offer the same deal to all members. If the UK allowed goods to cross between Ireland, the EU and NI without checks, inspection or tariffs, the rest of the WTO members could argue that Ireland and by extension the EU are getting a better deal than they are. They could then insist the UK enforces the rules at the border, cuts tariffs for them to the same level or retaliate or seek compensation.

There are some who argue we should just reduce all tariffs and quotas to zero unilaterally for every country in the world, although even its supporters have said that would have huge effects on the UK's agricultural and manufacturing industries. This is also not necessarily a solution to the border problem, ultra-cheap imports into the UK of steel, steaks, salmon and sewing machines, could cross the border and undercut Irish producers.

What can be done?

There are five possible solutions.

1. Ireland leaves the EU and rejoins the UK - not going to happen

2. Northern Ireland leaves the UK and unites with Ireland - not going to happen

3. The UK leaves the EU but stays in the Single Market, the Customs Union and probably the Common Agricultural Policy - already ruled out by the UK government

4. A hard border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland - rejected by all sides.

That leaves:

5. Squaring the circle. Over the coming months and years of negotiation and transition, a compromise position including technology, special exemptions and "regulatory alignment" is hammered out. Keeping the border invisible while securing the sanctity of the Single Market and the unity of the United Kingdom.

Given the first four options are to varying degrees unacceptable to the Irish government, the British government and the DUP, the clever money is still on squaring the circle.

- Published5 December 2017

- Published5 December 2017