Helping women ensure their voices are heard

- Published

'Women get interrupted a lot', says Facebook's Nicola Mendelsohn

"I remember early in my career that sometimes I would have a thought in my head, but I lacked the confidence to be able to get that thought out," says Nicola Mendelsohn.

"Then I would hear, usually a man, say the point that I had in my head, and I'd kick myself."

Nicola Mendelsohn, Facebook's vice-president for Europe, the Middle-East and Africa, has been described as the most powerful British woman in the tech industry.

She leads a team of hundreds and says she is "open, concise and clear" when speaking. However, she says women still face a significant communication problem in the workplace.

"Women get interrupted a lot, or people talk over them. I think there is an element that happens in the workplace where we actually condition women not to speak," she tells the BBC's The Why Factor.

Her anecdotal evidence is backed up by linguistic research. Despite the popular belief that women talk more than men, studies consistently suggest it's actually men who hog most of the airtime.

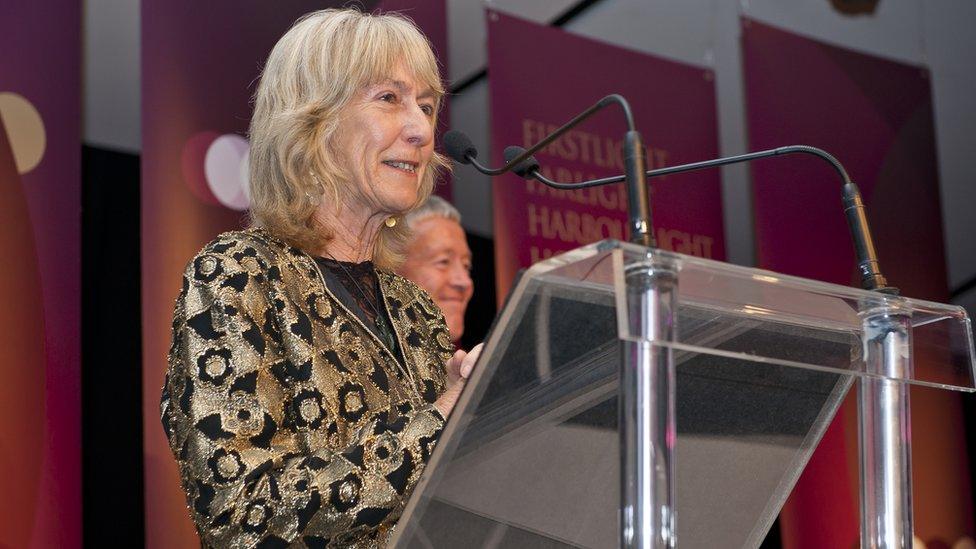

Janet Holmes says her research found that men tended to ask more questions in public meetings

And having more women in meetings doesn't help. The authors of the book The Silent Sex , externalfound in research that men out-talked women even when the group was 60% female. Women only spoke as much as men when they outnumbered them four to one.

Men are generally more vocal in other public forums too.

Listen to the BBC World Service's The Why Factor on Men, Women and Language

In public meetings, men asked three-quarters of the questions, on average, while making up only two-thirds of the audience, according to analysis by Janet Holmes, professor of linguistics at Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand.

They asked almost two-thirds of the questions when the audience was split equally.

Be assertive

So how can women ensure their voices are heard? A quick online search will yield a plethora of advice.

A lot of it centres on the idea that women aren't assertive enough in their use of language. The Washington Post even described "woman in a meeting" as a language of its own, external.

A recent viral blog post by a former Apple and Google employee advised women to stop using the word "just", external, describing it as a "subtle message of subordination, of deference" that is used more frequently by women than men.

Most linguists say it is impossible to generalise about male and female speech patterns

And in 2014 the shampoo brand Pantene released an advert encouraging women not to say sorry too much, external. It opened with the question "why are women always apologising?"

Sorry, are they?

According to Oxford University language professor Deborah Cameron the truth is much more complicated.

Although most linguists acknowledge that any social division, including gender, is bound to affect the use of language, she says it's impossible to generalise about male and female speech.

"Almost all cultures have stereotypes and beliefs about this," says Prof Cameron. "What's interesting is that there's disagreement over what the differences actually are.

"In some cultures they think women are much more direct than men, in fact they're seen as too direct and even rude.

"In the West, the stereotype is the other way around; women are timid, diplomatic, and avoid rudeness and conflict."

True or false?

Women talk more than men: Despite this longstanding belief, research consistently shows the sexes use roughly the same number of words a day, and men tend to dominate in conversations across a range of contexts

Women apologise more than men: There's no evidence to suggest that women apologise more

Men interrupt more than women: This one is true and has been borne out by linguistic research

Men use more aggressive language: No, men and women use a range of linguistic styles and there are as many differences between individual men and women as there are between the sexes

Both Prof Cameron and Prof Holmes say these stereotypes are just that. In practice both men and women draw on aspects of language that are stereotypically masculine and feminine, depending on the context and what they want to achieve.

"There's as much difference among men or among women as there is between the two," says Prof Cameron.

Competent but disliked

However, for women, there can be a cost to using "male" language.

"There's something psychologists call the competence likeability problem," says Prof Cameron. "A woman who is judged competent will be seen as less likeable."

A US study of performance evaluations in the tech sector found that women were much more likely than men to be given negative feedback, external about their personality or manner.

Words like "bossy", "abrasive", "strident", and "aggressive" cropped up repeatedly for women, but not for men.

Women are more likely to be given negative feedback about than men

Nicola Mendelsohn says she was given this feedback early in her career, but has learnt to ignore it.

"Those are words that are used differently for men and for women. And for women they're usually used in a negative way, but for men they're used, weirdly, in a positive way. So I see it as an example of bias."

Because of this bias, Prof Cameron argues that following advice to be more direct could in fact be counter-productive.

"There's this whole industry that says 'empower yourself by changing the way you speak and you'll be treated like men are'. In fact unfortunately that isn't the case; women are not judged in the same way as men.

"A woman who asserts herself is judged as bossy and aggressive because it goes against our stereotype of what feminine behaviour ought to be. So the answer isn't just to imitate men."

Which begs the question, what is the answer?

"The men matter as much as the women here," says Nicola Mendelsohn. "Men can be the allies here.

"We need men to actively sponsor women, for men to say, 'I back you, I believe you can do this, how can I help you?'."