Water bills set to fall by up to £25 from 2020

- Published

- comments

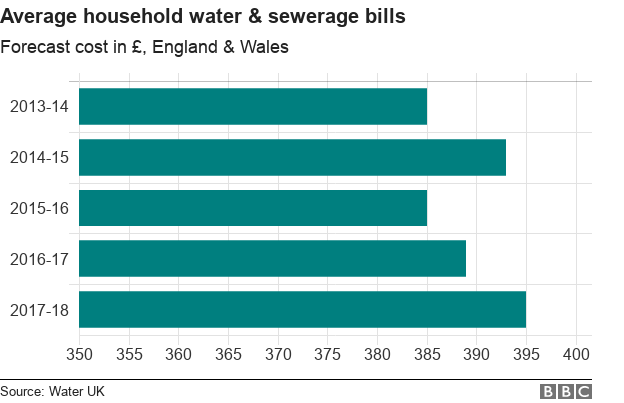

Household water bills in England and Wales will fall by between £15 and £25 a year from 2020 to 2025, the regulator Ofwat has pledged.

A forthcoming price review will give water companies less wiggle room to recover the costs of debt and equity from customers, the regulator said.

Ofwat was criticised by an influential government committee in 2016 for overestimating water firms' costs.

Water UK, said it was a "tough challenge from Ofwat".

Consumers can look forward to a real terms fall in water bills, Ofwat said.

Since privatisation in 1989, water bills have risen above inflation by about 40%, leading to a debate about whether privatisation works for that industry.

The regulator's chief executive, Cathryn Ross, told the BBC: "We have an early view on the financing costs that we're going to enable companies to recover from their customers.

"That's the biggest single driver of the bill. Financing costs are about a third of the average bill."

She said those financing costs for water companies had come down from 3.74% in 2014 to 2.4% now, and that difference can be passed on to customers.

But companies are allowed to add the cost of inflation on to bills.

So from 2020, customers will be paying less than they would have been paying had the price controls not been set at that level by Ofwat, but there may not be an actual, noticeable fall in the bill.

Michael Roberts, Chief Executive of Water UK, said Ofwat's review would be "tougher for some companies than others".

However, he added: " The industry has a strong track record in providing customers with a world class product and service.

"We've cut bills, increased help for the less well-off, and reduced leakage by a third, and we are committed to achieving even more for customers in the future."

The final Ofwat price review will be published in 2019.

Analysis: BBC Today programme business presenter Dominic O'Connell

Jeremy Corbyn has a simple remedy for the perceived excessive profits and underperformance of water companies - nationalisation.

Ofwat's answer is not so easily digestible - 260 pages of dense regulatorese, full of catchy concepts like the "weighted average cost of capital for appointee companies".

The headline savings promised, just £15 to £25 a year from an average bill in the five years from 2020, will also not set many hearts racing.

Ofwat's problem is that the companies it regulates have by and large prospered despite its successive attempts to crack down on returns.

Severn Trent, the largest quoted water company - one that has shares listed on the stock exchange - has promised its shareholders dividends of inflation plus 4% for the foreseeable future, an astonishing return for what is a low-risk utility stock.

Ofwat needs to find a much sharper tool if its solution, rather than Mr Corbyn's, is to catch the public imagination.

Ms Ross said nationalisation would be a political decision, but that since privatisation, water firms had invested £140bn.

"There has to be a question about whether government would do that if that were to land on the public balance sheet, but of course, government can borrow more cheaply," she said.

In a price review, Ofwat looks at the costs of financing that water firms face; the costs of service, such as how much it costs to transport water or treat it; and it looks at how water firms can improve their service.

In 2016, the Public Accounts Committee (PAC) said Ofwat had consistently overestimated water companies' costs.

Ms Ross said the regulator had taken a view in 2009 of what the financing costs would be, and "actually the financing costs were a lot lower than that, and that's really why the MPs were criticising us".

"We've taken that on board, and that's why today... we're taking a tougher line," she added.

'Claw back'

The Consumer Council for Water, a watchdog, said an Ofwat decision to get rid of a cap on rewards for beating performance targets "could open the door to bill instability" after 2019.

Tony Smith, the watchdog's chief executive, said: "This could hand companies an opportunity to claw back some of the money they would be unable to get through lower financing costs and it could lead to bill increases which many customers view as rewards for doing the day job."

- Published30 November 2017

- Published21 November 2017

- Published20 September 2017