Wage squeeze continues for British households

- Published

- comments

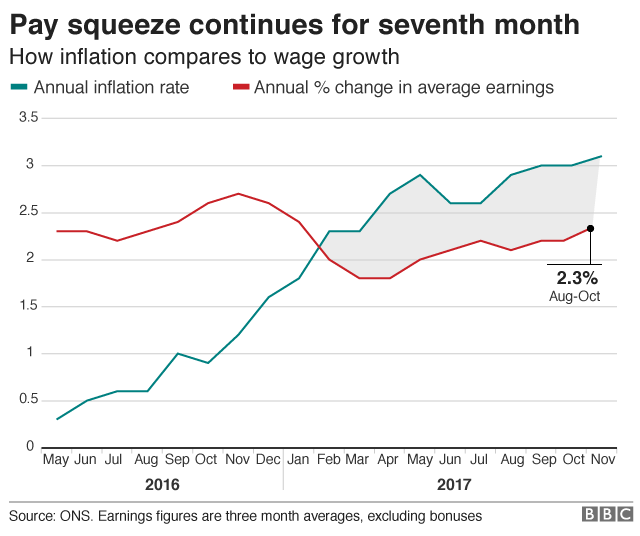

Wage growth fell behind inflation for a seventh month in a row, according to new employment figures.

The Office for National Statistics said average weekly wages rose by 2.3% in the three months to October, below inflation at 3%.

Real earnings, which take into account the cost of living, fell by 0.4%

Unemployment declined by 26,000 to 1.43 million, while the jobless rate remained at 4.3%, the lowest since 1975.

However, while unemployment fell, the decline was not as steep as the 59,000 drop recorded in the three months to September.

The pressure on household finances is likely to worsen as the most recent figures for inflation showed a rise to 3.1% in November - the highest in nearly six years.

John Hawksworth, chief economist at PwC, said: "Real pay levels continue to be squeezed, and we expect this to persist for at least the first half of 2018, further dampening consumer spending growth."

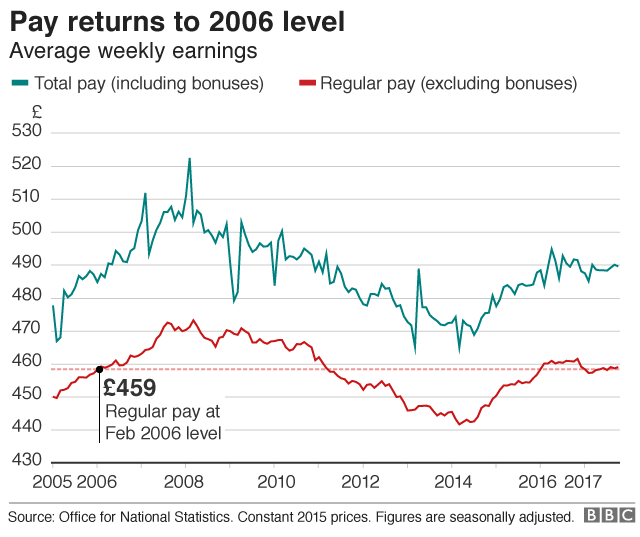

Average weekly pay, excluding bonuses, reached £478 which is the lowest since February 2006.

However, average weekly wages were ahead of the 2.2% rise in the three months to September.

Ben Brettell, senior economist at Hargreaves Lansdown, said: "The pay squeeze continues for now, but with wages growing a little more strongly and inflation set to fall back in the new year, this looks like it'll come to an end in the next few months."

How has pay for your job performed against inflation?

If you cannot see the calculator, click here, external.

Produced by Daniel Dunford, Alison Benjamin, Ransome Mpini, Evisa Terziu, Joe Reed, Luke Keast, Mark Bryson and Shilpa Saraf.

The number of people claiming benefits principally for the reason of being unemployed rose by 5,900 to 817,500 in November.

Economists had expected the number of claimants, which is considered to be a potential early warning sign of an economic downturn, to rise by 3,200, according to Reuters news agency.

The number of people in employment also dropped, down by 56,000 to 32 million, with men the biggest casualties of the decline.

The level of employment fell by 50,000 for men and by 6,000 for women. The biggest fall was for men aged 18-24 years old.

Analysis: Andy Verity, economics correspondent

What is striking about these figures is that the number of people employed is shrinking.

In the three months from August to October, there were 32 million people working: still a lot and more than a year ago. But it's 56,000 fewer than the previous three months.

For most of the last six years - and indeed most of the last 30 - the workforce has been expanding. And it's happening in spite of 798,000 job vacancies. So we have a labour market that's tighter than ever - yet a workforce that's shrinking.

How can that be happening? Well one possible answer you may already have guessed. It has a lot to do with the slowdown in immigration. And it rhymes with "exit".

Howard Archer, chief economic adviser at the EY ITEM Club, said: "The latest data suggest that UK labour market strength is currently being diluted by extended lacklustre UK economic activity, as well as heightened business uncertainties and concerns over the economic and political outlook including Brexit.

"There are also reports that employment growth in some sectors is being limited by a lack of suitable candidates."

However, he said that employment was "still at a very high level", with the rate at 75.1%.

- Published12 December 2017

- Published29 November 2017

- Published23 November 2017