Robot warning over living wage rise

- Published

- comments

The rapid increase in the living wage could mean that more jobs are replaced by robots, the Institute of Fiscal Studies has warned.

The think tank said with the hourly rate set to top £8.50 per hour by 2020, more jobs may be at risk of automation.

Firms are more likely to invest in robots and computerised systems if the alternative is more expensive labour.

Report author Agnes Norris Keiller said "beyond some point a higher minimum must start affecting employment".

"We do not know where that point is.

"The fact there seemed to be a negligible employment impact of a minimum [wage] at £6.70 per hour - the 2015 rate - does not mean the same will be true of the rate of over £8.50 per hour that is set to apply in 2020," the research economist at the IFS added.

Too high?

The IFS makes the point that if the living wage was set at £100 an hour, for instance, then clearly a vast number of people would be priced out of the labour market.

Of course, the think tank is stretching reality towards the absurd to make a point - but the underlying economic theory still holds.

A minimum wage that is "too high" could affect the very people it is supposed to help.

"The fact the higher minimum will increasingly affect jobs that appear to be more automatable is an additional reason why extremely careful monitoring is required," Ms Norris Keiller said.

"Even higher rates, as proposed for example by the Labour Party, would bring even more employees in more automatable jobs into the minimum wage net."

Hotel cleaning jobs are not easily automated

The IFS said that in 2015 the minimum wage was mostly paid to people in lower wage personal service sector jobs such as hotel cleaning or nursery working.

Such jobs are not easy to automate.

But as the living wage rises faster than average earnings, more people are paid at that level.

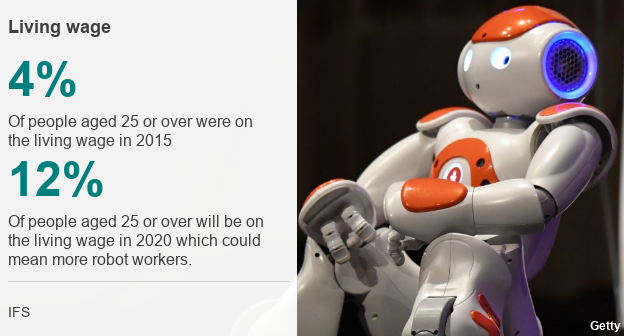

In 2015, 4% of people aged 25 or over were on the living wage.

That is set to reach 12% by 2020.

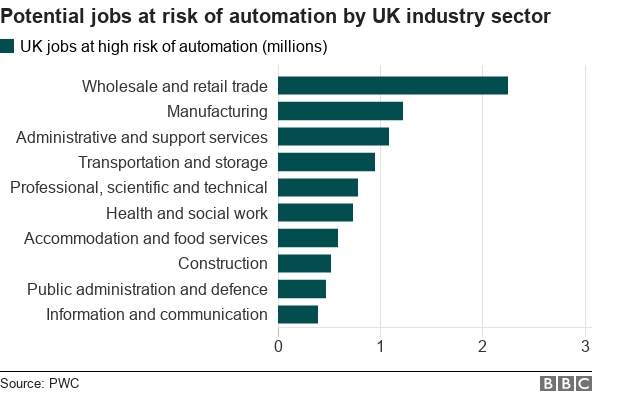

And will increasingly include jobs - such as retail cashiers and bank clerks - which are more susceptible to being replaced by computerised systems.

The then chancellor, George Osborne, introduced the "National Living Wage" with a political flourish in his 2015 Budget.

He announced the new scheme would start at £7.20 an hour for the over-25s and rise to £9 an hour by 2020.

It replaced the £6.50 an hour minimum wage.

Mr Osborne said that "Britain deserves a pay rise and Britain is getting a pay rise".

And, the government points out, the present living wage should be seen alongside record employment levels.

A spokesman said: "The National Living Wage is creating a stronger economy and a fairer society, having delivered the fastest pay rise for the lowest earners in 20 years.

"But we also want to create highly-skilled, well-paid jobs for the future backing innovation and supporting the development of new skills through our Industrial Strategy."

Whatever the employment risk level of the living wage, we do not appear to have hit it.

And there have been plenty of warnings before about the minimum wage leading to unemployment which have been wrong.

Labour, not to be outdone on living wage levels, said in its 2017 election manifesto that it would increase the wage rate to £10 an hour.

Rebecca Long Bailey, Labour's shadow secretary of state for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy said "technological change, if harnessed effectively, could bring about immense benefits".

"All workers should be paid a full and fair wage. Higher wages, good jobs, greater investment in skills and technology to boost productivity and high employment all go together. They are complements, not trade-offs," she added.

The problem is, according to the IFS, there is not a simple relationship between supporting high paid jobs and increasing the living wage.

We might all want a high paid, high skilled economy.

But that can take decades to deliver.

Increase the living wage too quickly in the meantime and higher levels of unemployment could be the result.