The 'making stuff' boom - here’s why it matters

- Published

- comments

Global customers key for manufacturing firm

It is unlikely you will have heard of Brandauer.

It is one of those small manufacturing businesses that are the backbone of the UK economy.

From its base in Birmingham, it makes high-precision metal tools and components for the car, household, aerospace and medical sectors and it employs more than 60 people.

If you have a kettle, it almost certainly relies on a small piece of Brandauer kit - more than 90% of the switch mechanisms in all the kettles in the world (and, yup, that's billions of them) are manufactured by the firm.

This is a small but significant British success story.

Brandauer's chief executive is Rowan Crozier.

And he knows all about the manufacturing boom reported on Wednesday by the Office for National Statistics.

I asked him what had led to the bulging order books of the last year which have resulted in more workers hired, in sharp contrast to the six months following the referendum in 2016 when a downturn in business confidence led Brandauer to cut costs and lay off staff.

"Initially it was the weaker pound, as a company we export 70% of what we make," Mr Crozier explained.

"[But then] global economic growth very much set us up for future growth in 2018, our customers are doing well and technology demands are ever increasing, which means as a net result we will do well."

Parts for kettles are only part of Brandauer's portfolio

For many manufacturing firms which have a clear strategy, invest in new kit (Brandauer's new Swiss high-tech manufacturing machines are the only ones in the UK) and export to the rest of Europe, Asia and North America, this is something of a sweet spot.

British manufacturing is riding high on two big trends - a weaker currency and global growth.

Sterling's fall in value following the Brexit referendum has made UK exports more competitive.

And for the first time since the financial crisis, the three main engines of global growth - the US, China and Europe - are performing strongly at the same time.

That has led to car exports, for example, rising rapidly - contributing to a narrowing of the trade deficit with the rest of the world.

That's the difference in value between what we import and what we export.

Domestically, the economic picture is more subdued, with growth still sluggish.

The weak construction figures are testament to that.

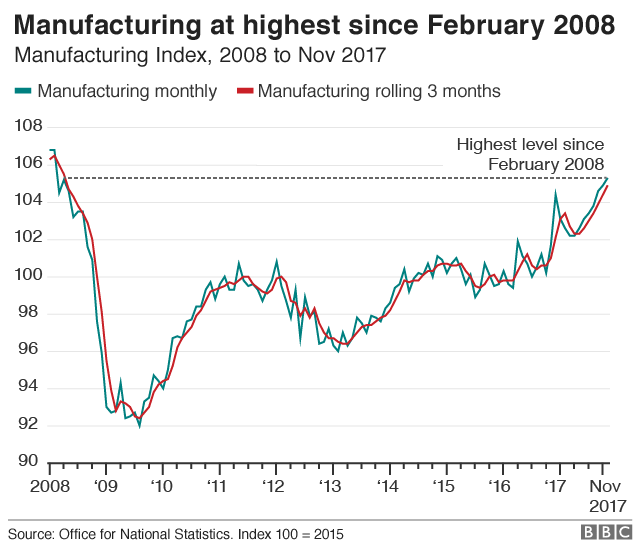

But, helped by that positive world outlook, Britain's manufacturing sector has not seen such buoyancy since April 2008 and the financial crisis.

And is enjoying its strongest run of growth since 1997.

Yes, manufacturing is only a relatively small part of the economy and is dwarfed by our services sector which makes up 80% of our national wealth.

But, if it does well, it is a sign of increasing confidence in the UK.

On Wednesday, the National Institute of Economic and Social Research predicted that growth for the final three months of 2017 could hit 0.6%, up from 0.4% for the July to September period.

The forecasts are certainly becoming more bullish.

And Wednesday's manufacturing figures will do nothing to dampen them.

- Published10 January 2018