Where did it go wrong for Carillion?

- Published

Construction giant Carillion is going into liquidation after its huge financial troubles finally overwhelmed it.

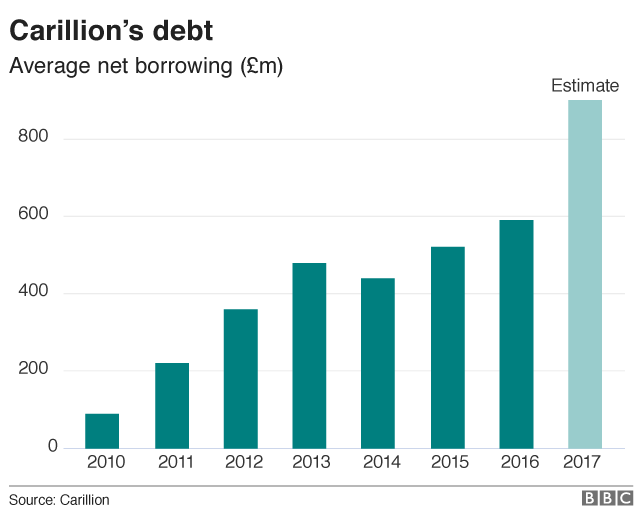

The UK's second-largest construction company buckled under the weight of a whopping £1.5bn debt pile.

Despite discussions between Carillion, its lenders and the government, no deal could be reached to save the company.

The big concern is over the disruption this might cause, given Carillion holds so many government contracts - from building hospitals to managing schools.

It also employs about 20,000 people in the UK and has more staff abroad.

So how did the company get into such dire straits?

What does Carillion do?

Carillion specialises in construction, as well as facilities management and ongoing maintenance.

It has worked on big private sector projects such as the Battersea Power station redevelopment and the Anfield Stadium expansion.

But it is perhaps best known for being one of the largest suppliers of services to the public sector.

Carillion worked on the Battersea Power Station revamp

Notably, it is part of a consortium that holds a contract to build part of the forthcoming HS2 high speed railway line, and it is the second largest supplier of maintenance services to Network Rail.

It also maintains 50,000 homes for the Ministry of Defence, manages nearly 900 schools and manages highways and prisons.

How big is it?

Very. Carillion employs 43,000 staff globally, around half of them in the UK where it does most of its business. It also operates in Canada, the Middle East and the Caribbean.

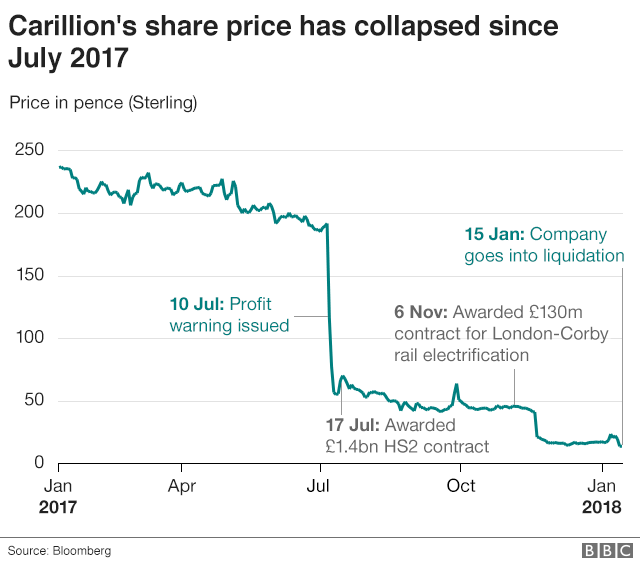

In 2016, it had sales of £5.2bn and until July boasted a market capitalisation of almost £1bn. But since then its share price has plummeted, leaving it worth just £61m.

What went wrong for the firm?

Some argue that it overreached itself, taking on too many risky contracts that proved unprofitable. It also faced payment delays in the Middle East that hit its accounts.

Last year, it issued three profit warnings in five months and wrote down more than £1bn from the value of contracts.

This made it much harder to manage its mountainous £900m debt pile and £600m pension deficit.

In December, the firm convinced lenders to give it more time to repay them.

However, the company's banks, which include Santander UK, HSBC and Barclays, were reluctant to lend it any more cash.

What were Carillion's biggest setbacks?

Among its biggest problems were cost overruns on three public sector construction contracts:

The £350m Midland Metropolitan Hospital in Sandwell. The opening was originally scheduled for October 2018, but difficulties with the heating, lighting and ventilation systems forced a delay of the launch date to spring 2019

The £335m Royal Liverpool Hospital. The new 646-bed hospital was due to be finished by March 2017, but the completion date has been repeatedly pushed back amid reports of cracks in the building

The £745m Aberdeen bypass, which is being built by the Aberdeen Roads Ltd consortium, a joint venture that includes Balfour Beatty and Morrison Construction alongside Carillion. It is due to open in spring 2018. One key stretch was due to open a year earlier, but was delayed because of slow progress in completing initial earthworks. Last month, environment watchdogs slapped a £280,000 penalty on the consortium for polluting two of Scotland's most important salmon rivers

Why does its collapse matter?

As Carillion is such a big supplier to the public sector, some fear there will be a lot of disruption.

Labour MP Jon Trickett told Parliament before the announcement that if it went under, it would risk "massive damage" to a range of public services.

Thousands of jobs also hang in the balance. Unions have said workers do not deserve to be caught in the crossfire and have urged the government to safeguard their jobs and bring Carillion's contracts back in house.

The government, which has praised Carillion's work on projects such as Crossrail, has said it will provide funding to maintain the public services run by the firm.

Analysts say Carillion had a large order book of business lined up.

The big question is, who will ultimately pick up its loss-making public contracts - another outsourced services provider or the government itself?

- Published12 January 2018

- Published7 January 2018

- Published3 January 2018