What does a government shutdown cost?

- Published

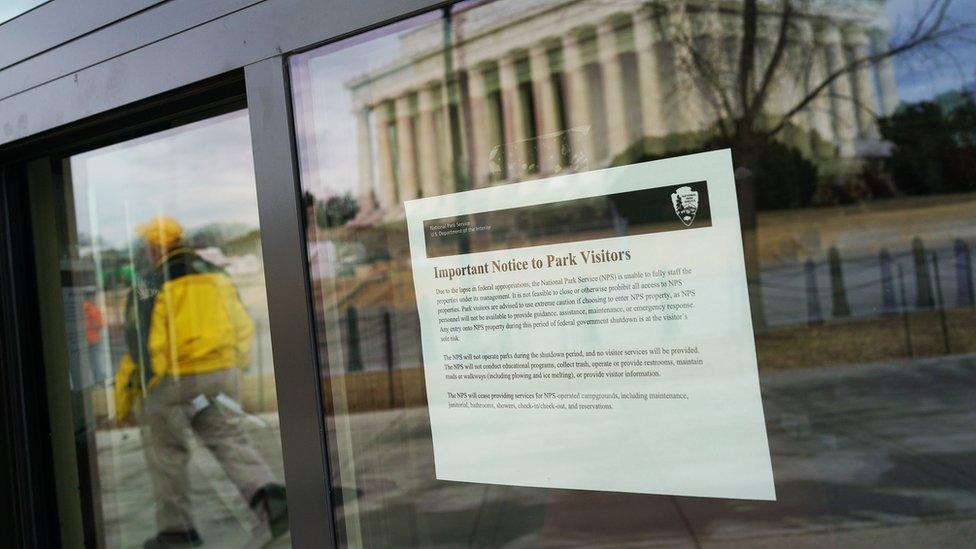

A kiosk at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington explains what is going on

A stand-off over the budget has led to a temporary shutdown of the US government. What will be the economic cost?

The Senate has reached a compromise to reopen the government, as the impasse entered a third day.

But while that brings a short-term spending deal closer - it must be approved by the House - some economists worry it could signal bigger problems to come.

How much does this cost the taxpayer?

The temporary solution could help the US avoid one of the most direct consequences of the shutdown - lost hours by federal workers.

In 2013, when the government shut down for 16 days, workers eventually received about $2bn for the furloughed time.

The Bureau of Economic Analysis estimated, external that the lost hours - at national parks, permit offices, federal loan programmes and the like - lowered economic growth in the fourth quarter by 0.3%.

There were also indirect effects, as the shutdown limited tourist activities and delayed pay cheques squeezed consumer spending.

And some government contractors - who number in the hundreds of thousands - never regained the pay lost during the period.

So will this hurt economic growth?

In 2013, the combination of indirect and direct costs amounted to as much as 0.6% of quarterly GDP or $24bn, according to some analyses, external.

This time around, the Trump administration worked to limit the effects, keeping some national parks open and deeming more employees to be "essential" workers.

Beth Ann Bovino, chief economist at S&P Global, says this will go down as a "blip" for the US economy.

But the problem could repeat itself when the temporary spending bill runs out.

A prolonged shutdown can hurt economic growth.

Goldman Sachs estimates that each week of a shutdown could lead to roughly 0.2% reduction in quarterly GDP growth.

What about the stock market?

As Congress headed towards a shutdown last week, US markets closed at record highs, again.

Analysts say it is possible that the dysfunction could cause investor attitudes to swing, but the reaction during previous shutdowns suggests the effect will be modest.

On the first day of shutdowns in prior years, markets fell an average of 0.9%, according to Goldman Sachs.

And during three of the longest episodes (in the 1990s and in 2013), markets eventually gained 1.2% by the time the shutdowns ended.

Are there long-term consequences?

Previous shutdowns have forced the two sides to come together, helping to provide policy certainty.

But unlike previous shutdowns, this one is happening when a single party controls both the White House and Congress.

That has some economists worried that the gridlock over the budget is a preview of more battles to come - which would pose more problems than the short-term economic consequences would suggest.

"The direct economic costs of a government shutdown, either today or later this year, should be minimal, but it's easy to craft a scenario where the shutdown causes bigger problems down the road by boosting partisan conflict and policy uncertainty," Moody's Analytics writes.

US political dysfunction was a primary factor when S&P downgraded the US debt rating in 2011, a move that has the potential to raise the cost of borrowing.

Questions over the debt level are expected to surface again this spring.

Moody's also estimates that policy uncertainty could lead to about 2.1 million fewer new jobs over a two-year period.

But the firm warned it may be overstating the effects.

After all, as Ms Bovino says, when it comes to US government dysfunction, "investors have gotten used to it".

"We've been here so long now," she said. "It weighs on business confidence. I don't know how much though."

- Published6 August 2011

- Published22 January 2018