A true picture of US black jobless figures

- Published

The black unemployment rate has declined but disparities remain

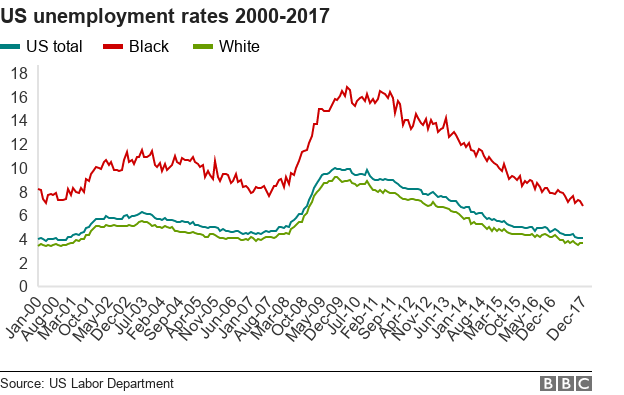

The unemployment rate for US black workers jumped to 7.7% last month, reversing course after falling to a record low in December.

The new figures were a potentially awkward turn of events for President Donald Trump, who has bragged repeatedly about the decline.

Even before the latest data, however, critics have said the president's celebration was premature, pointing to the persistent gap between black and white unemployment rates.

Job gains in 2017 pushed the black unemployment rate down in December to 6.8%.

While that was the lowest rate since the US started tracking the figure in 1972, it remained by far the highest of racial groups.

Members of the Congressional Black Caucus during President Trump's State of the Union speech did not clap when he mentioned the unemployment rate

The national unemployment rate has fallen 60% since 2009 to 4.1% - a level not seen since the start of the century.

The white unemployment rate was 3.7% in December, while it hovered at 2.5% for Asians and at 4.9% for Hispanic and Latinos.

"The decline has occurred in the unemployment rates for everyone," says William Darity, a public policy professor at Duke University. "That's the big problem I have using this as some kind of signal of an event to be celebrated."

Can Trump claim credit for the decline?

Economists say slow and steady growth since the end of the recession is responsible for the job gains, much of which pre-date the Trump administration.

In 2017, Mr Trump's first year in office, the black unemployment rate fell by about 1 percentage point.

That is roughly on par with the annual pace of improvement during the final years of the Barack Obama administration.

US President Donald Trump promotes his economic policies at the World Economic Forum

The president has touted deregulation and corporate tax cuts as lifting business confidence and spurring hiring.

But US Department of Labor figures show total job gains actually slowed under President Trump. Last year, employers added about 2.1m jobs - the smallest number since 2010.

"There is certainly a genuine decline [in the unemployment rate], but I would argue that it has little to do with him," says Lisa Cook, an economics professor at Michigan State University.

"It has to do with a recovering economy and that didn't start start in January 2017."

The January rate of 7.7% among black workers was the highest since April. (The unemployment rate for white workers, however, edged lower to 3.5%.)

Some degree of monthly variation is expected, but last month's rise is large enough to suggest the downward trend might be over, says William Spriggs, an economics professor at Howard University and chief economist at the AFL-CIO labour union.

"I would be concerned that January isn't just the normal fluctuation," he says.

Is the gap between blacks and whites narrowing?

The black unemployment rate has been roughly double that of the white rate for decades.

While that has narrowed periodically - including in the last few years - the figures can be hard to parse.

The smaller gap is not evident, for example, if the black unemployment rate is compared to that of only non-Hispanic whites.

By other measures, serious disparities persist.

White families in the US typically have about seven times the wealth of black families, according to the 2016 Survey of Consumer Finances, external, an annual report from the US Federal Reserve.

White households are also significantly more likely to own a home and car, and have retirement accounts or other investments.

If the job gains of recent years were to continue, those differences could start to diminish, says Mr Spriggs.

But the pace of job creation is slowing. And meanwhile, "those gaps are huge".

President Trump's focus solely on the decline is perceived as a "lack of recognition" that the disparities remain a problem, says Hilary Shelton, a senior vice president for policy and advocacy at the NAACP civil rights organisation.

He adds that the president's policies compound those concerns.

"We have not heard any discussion about what he hopes to do to specifically address the disparity that has been rather consistent," he says.

How much of this is due to racism?

The racial gap in unemployment rates has persisted even though today's black workforce is better educated and has more skills than it had in previous decades, says Mr Spriggs.

He says that is why "it convinces me that I really am looking at discrimination".

The president has faulted black athletes for protesting during the national anthem

In that light, economists say the president's record of racially charged remarks - such as blaming "both sides" for violence after a white supremacist rally in Virginia last year - is troubling.

"People, firms are following the president's lead and it's open season for discrimination," says Ms Cook.

In an interview with CNN, the rapper Jay-Z said the president's celebration of the black unemployment rate was "missing the whole point".

"It's not about money at the end of the day," he said. "You're missing the whole point. You treat people like human beings."

Are there any signs of progress?

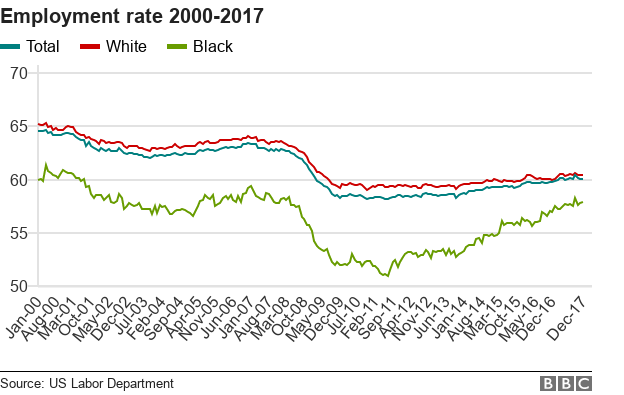

The percentage of the working age black population that is employed has also nearly rebounded since the recession to almost 58%.

Though the level remains lower than the previous record and lower than the roughly 60% for whites, the gap between the two races is smaller than it once was.

The narrowing comes as the share of the US working age population that is employed has fallen dramatically for all races, with an especially sharp drop occurring during the recession.

The decline, still not fully understood, has been explained by a mix of factors, including opioid addiction, automation and early retirements after job losses during the recession.

The white population is aging more quickly than the black population, which may explain part of the recent convergence.

The rebound among black workers also suggests they are less deterred by the low wages that have characterised many of the new jobs, Mr Spriggs says.

Wage growth was relatively strong in January. But as the president's precipitate celebration of unemployment reminded, it is prudent not to read too much into one month's figures.

- Published5 January 2018

- Published29 January 2018

- Published8 January 2016