Mothers suffering 'pay penalty' at work, report suggests

- Published

A key pay factor was women working part-time in motherhood, the report suggests

Mothers in part-time jobs are being hit by a "pay penalty" and are often not given pay rises linked to experience, a new study has suggested.

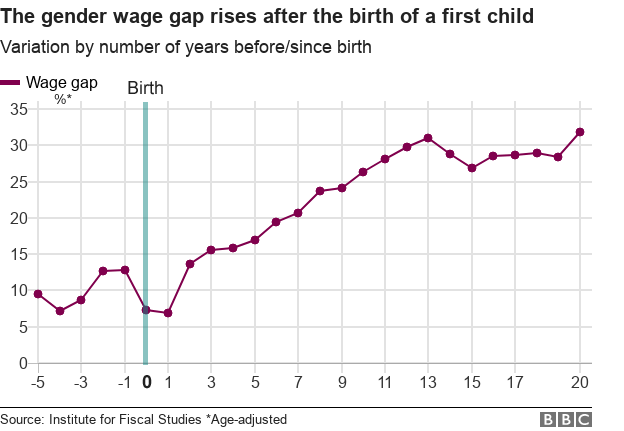

The Institute for Fiscal Studies report found by the time a couple's first child is aged 20, many mothers earn nearly a third less than the fathers.

A key factor was women working part-time in motherhood, the report said.

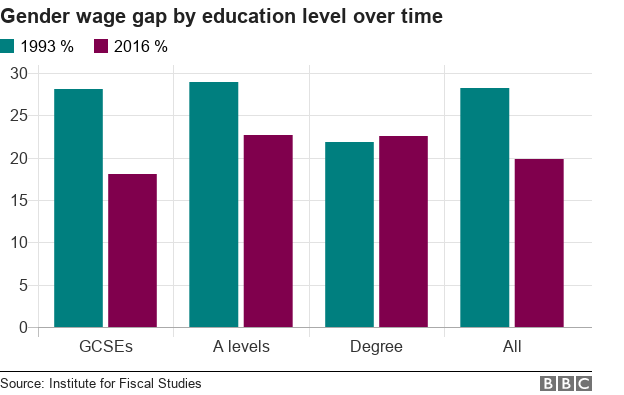

A gender pay gap between graduates has not improved since 1993, despite gaps narrowing for non-graduates, it added.

The study, compiled on behalf of the independent Joseph Rowntree Foundation charity, found when women become mothers and start to work part-time they may miss out on the benefits of full-time employment - where experience is rewarded with progression and higher pay.

'My wages have more than halved'

Yasmin Latif from Bow, in London, was a deputy head teacher at an inner city sixth form college.

She earned £49,000-a-year, but decided to seek part-time work so she could care for her elderly mother.

The 49-year-old said: "You almost lose your status if you go down to part-time work, you're not allowed to be a head of year or a head of department if you're working part-time."

Now she works as a lecturer three days a week for £22,000-a-year.

"I earn what I did as a graduate 30 years ago," she said.

She added that she has had use her life savings in order to pay the bills.

"The effect of part-time work in shutting down wage progression is especially striking," the report added.

"Whereas, in general, people in paid work see their pay rise year on year as they gain more experience, our new research shows that part-time workers miss out on these gains."

The vast majority of part-time workers were women, especially mothers of young children, the report said.

It said the lack of earnings growth in part-time work particularly affects graduate women, "because they are the women for whom continuing in full-time paid work would have led to the most wage progression".

One example in the report is that of a graduate who has worked full-time for seven years before having a child.

If she continued in full-time work for another year she would on average see her hourly wage rise by 6%.

She would see "none of that wage progression" if she switched to part-time work instead, say the report authors.

Do you know the difference between the gender pay gap and equal pay?

Monica Costa Dias, associate director at the IFS and a co-author of the report, said: "It is remarkable that periods spent in part-time work lead to virtually no wage progression at all."

The report also notes the narrowing of the non-graduate gender pay gap between women and men educated to GCSE-level with the difference in average hourly pay falling from 28% in the early 1990s to about 18% in 2016.

The report said this change from 1993 is because "women in work are now better educated relative to men than they were".

The research shows women with A-levels have seen the wage gap close from 29% in 1993 to around 22%.

By comparison, it found the average hourly wages of men and women with degrees differed by 22% in 2016 - compared with 21% in 1993.

Robert Joyce, associate director at the IFS and co-author of the report, said: "Traditionally it has been lower-educated women whose wages were especially low relative to similarly educated men.

"It is now the highest-educated women whose wages are the furthest behind their male counterparts - and this is particularly related to the fact that they lose out so badly from working part-time."

The report said a key challenge for future research was to understand why part-time work shuts down wage progression so much.

"There are a number of possibilities, including less training provision, missing out on informal interactions and networking opportunities, and genuine constraints placed upon the build-up of skill by working fewer hours," it said.

However, even before women have their first child, the IFS said they were on average being paid 10% less than men.

Mr Joyce said new legislation that requires UK companies with more than 250 employees to publish their gender pay gaps "could be part of the solution" since women may not be aware that men were being paid more than them.

Your experiences: Part-time workers share their thoughts

Lynsey Reynolds, Cardiff

I went part-time in 2012 after having twins, due to the affordability of childcare.

At the time I had a good career in NHS finance. However I was subsequently told by my manager in the NHS that while I was part-time I would never get anywhere working for him.

I ended up leaving the NHS to work for a smaller organisation who needed a part-time finance manager.

It still rankles that I was forced to choose between motherhood and my career in the NHS.

Sharron Wilson, Warwickshire

Sharron worked in project management for six years but then decided to pursue a Masters and a PhD. After having two children and completing her studies, she returned to part-time work in administration.

The biggest problem is a shortage of well-paid part-time jobs.

They are few and far between and when they come out, competition is fierce.

I get paid an okay amount, but never see anything part-time the next grade up. So I may have to wait another few years, when the children are older, before going back full-time, and then all the job opportunities will be open to me.

Cat McGrann, Kingston-upon-Thames

Cat works part-time so she can care for her two young children. She said that her salary has not increased by much.

I have a good job with decent pay, but am working a 70% job for £500-a-month after nursery fees.

If I worked full-time and we needed full-time childcare, it would be £300 [after childcare fees].

What was a choice is now a trap.

For most families [part-time work] is a financial necessity and women take the hit with diminished careers, missed promotions, lost earnings and lower pensions.

- Published31 January 2018

- Published30 January 2018

- Published6 January 2018