How long does it really take you to fall asleep?

- Published

- comments

How do you fall asleep? It might happen to us every night - and maybe sometimes more often - but it's still a deeply mysterious process.

An international group of researchers at the University of Cambridge is trying to find out what really happens in that drowsy twilight zone as we make the transition from waking to sleeping.

They are measuring, analysing and trying to understand how the conscious, controlled, waking person turns into an unaware, dreaming, sleeper.

They also want to know if this really is one of the most creative moments of the day.

Even though neuroscientists have carried out a huge amount of research on brain activity during sleep, the researchers at Cambridge say much less is known about the moments just before we enter sleep.

"Some people fall asleep very quickly, others take a long, long time," says Sridhar Rajan Jagannathan, a researcher from Chennai (Madras) in India, who has the unusual task of watching people fall asleep for a living.

Risk of accidents

This "transition" usually lasts between five and 20 minutes, says Mr Jagannathan, one of Cambridge's Gates Scholars, funded by a foundation set up by the US tech billionaire, Bill Gates.

But the behaviour within this time can be very different. For some, going into sleep is a smooth, uninterrupted descent. But others have more turbulence in the journey.

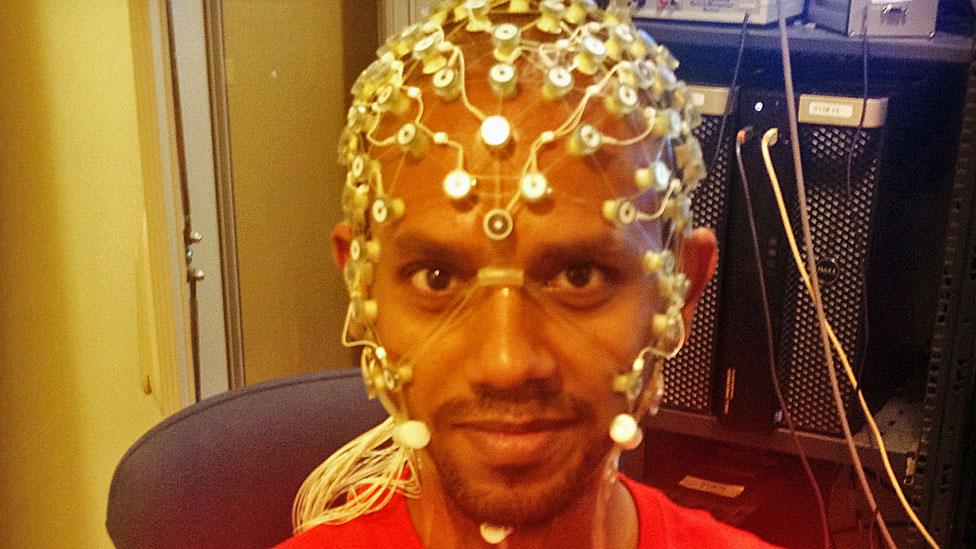

Sridhar Jagannathan wants to know what happens in the minutes before we are fully asleep

"Others begin to get drowsy and then come back to alertness," he says. They seem to "oscillate" between the urges to sleep and stay awake, in a much more fitful, stop-start entry into sleep.

Dr Tristan Bekinschtein, head of the laboratory where the Cambridge neuroscience team is working, said that some people can consciously pull themselves back up from the early stages of falling asleep.

He describes these moments between sleep and waking as the "mists of consciousness". It's that time when eyes glaze, attention wanders and waking thoughts begin to dissolve.

Mr Jagannathan's research is looking at how this pre-sleep phase might be linked to accidents and people making dangerous mistakes.

This could happen during the day while someone is working. They might appear to be awake and functioning, but if they begin to cross the threshold of sleep there are going to be significant risks.

'Small drift-offs, big problems'

"If you're doing some boring task, you might not really go into deep sleep. But you'd be in this drowsy period. You would know you're not alert, that you're drifting off," says Mr Jagannathan.

"Small drift-offs can cause big problems," he says. It's not only a safety concern for tasks such as driving, but for anything where concentration and decision-making are important.

The beginning of sleep can overtake us during the day, disrupting our ability to concentrate

In the Cambridge laboratories they study how response times change as people enter this zone.

Mr Jagannathan says there are research efforts to find ways to warn of the onset of sleep, identifying changes in eye movements or brain activity.

He also wants to understand why accidents in this drowsing stage seem much more prevalent among people who are right-handed.

There are also hopes that research into brain activity during falling asleep and waking might help stroke victims trying to regain lost physical functions.

Daydream believer

There are positive sides to the mysterious minutes at the borders of sleep. There seems to be a connection with creativity and imagination.

There are worries about the safety risks of the pre-sleep phase of tiredness

"Your inhibitions are less when you're in this state of transition. It makes you more creative," says Mr Jagannathan.

"You have more freedom to express yourself. You're more willing to make mistakes."

It supports the idea of artists, musicians and writers being inspired by these moments.

It also gives credence to the value of "sleeping on it" if there's something that needs extra creative thinking.

The research also casts light on how we connect with the outside world as we disappear into sleep.

Mr Jagannathan says that sounds and words might not get a response, but saying someone's name seems much more likely to make them wake up.

"It's very bizarre," he says, to observe the power of someone hearing their name in their sleep.

Keeping time

It gives researchers clues about how the brain functions - not like a machine detecting noises, but something that responds to a personal meaning, identifying a name from other sounds, even in sleep.

"The meaning of something is extremely important," says Mr Jagannathan.

A donation by Bill Gates has funded Sridhar Jagannathan's research at Cambridge

It's also wrong to think that when people are asleep that they don't have any awareness of time, Dr Bekinschtein says.

He gives the example of how someone might need to catch a very early flight - and they can wake up a few minutes before their alarm clock rings.

"The precision of timing is quite high. People seem to be able to judge how much time has passed, much more than you expect."

Dr Bekinschtein also confirms the great cruelty of sleep - the only time you can't fall asleep is when you really want to.

He says there have been experiments where students were given cash incentives to fall asleep as quickly as possible - and the pressure of trying to fall asleep had the opposite effect.

Mr Jagannathan says much more attention should be paid to how we let go and fall into sleep.

"When someone complains about sleeplessness, what people try to do is assess the quality of sleep. How long do you sleep? Do you wake up?

"But they never care about how well you fall asleep. That's more important and it's heavily related to the other problems."

More from Global education

Ideas for the Global education series? Get in touch with sean.coughlan@bbc.co.uk