Could plant-based plastics help tackle waste pollution?

- Published

Potato starch and plant fibres can be turned into compostable plastics

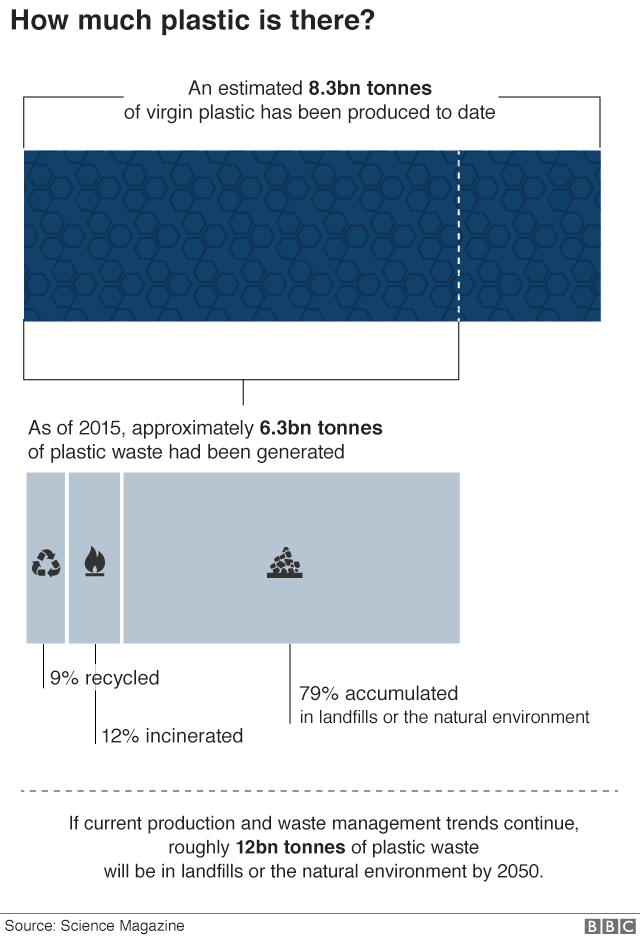

We know that plastic waste is a big problem for the planet - our oceans are becoming clogged with the stuff and we're rapidly running out of landfill sites. Only 9% is recycled. Burning it contributes to greenhouse gas emissions and global warming. So could plant-based alternatives and better recycling provide an answer?

We have grown to rely on plastic - it's hardwearing and versatile and much of our modern economy depends on it. And for many current uses there are simply no commercially viable biodegradable alternatives.

The humble single-use drinking straw is a case in point. Primaplast, a leading plastic straw manufacturer, says "greener" alternatives cost a hundred times more to make.

Takeaway coffee cups are another example. In the UK alone we throw away around 2.5 billion of them every year, many of us thinking that they are recyclable when they're not, due to a layer of polyethylene that makes the cup waterproof.

One company trying to change this is Biome Bioplastics, which has developed a fully compostable and recyclable cup using natural materials such as potato starch, corn starch, and cellulose, the main constituent of plant cell walls. Most traditional plastics are made from oil.

Biome Bioplastics has developed a full compostable takeaway coffee cup

"Many consumers buy their cups in good faith, thinking they can be recycled," says Paul Mines, the firm's chief executive.

"But most single-use containers are made from cardboard bonded with plastic, which makes them unsuitable for recycling. And the lids are most often made of polystyrene, which is currently not widely recycled in the UK and ends up in a landfill."

The company has created a plant-based plastic - called a bioplastic - that is fully biodegradable and also disposable either in a paper recycling or food waste bin.

Mr Mines believes it's the first time a bioplastic has been made for disposable cups and lids that can cope with hot liquids but which is fully compostable and recyclable. The cup isn't yet on the market, but Mr Mines says he is in talks with a number of retailers.

"It's not feasible to get rid of plastics completely," says Mr Mines, "but instead replace some of the petroleum-based plastic for biopolymers derived from plant-based sources."

Plenty of other companies and research institutes, such as Full Cycle Bioplastics, Elk Packaging and VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland, are working on similar biopolymer solutions that are more environmentally friendly but equally functional as conventional plastic.

Could plastic roads help to save the planet?

And Toby McCartney's firm MacRebur has developed a road surface material made from an asphalt mix and pellets of recycled plastic. The plastic mix replaces much of the oil-based bitumen traditionally used in road building.

"What we are doing is solving two world problems with one simple solution - the problems we see with the waste plastic epidemic, and the poor quality of the potholed roads we drive on today," claims Mr McCartney.

Since its launch two years ago, the Lockerbie-based firm's hybrid material has been used to build roads across the UK, from Penrith to Gloucestershire.

More than five trillion pieces of plastic are floating in our oceans, by some estimates, much of which can take up to 1,000 years to degrade fully. As it breaks up over time, tiny pieces end up being eaten marine creatures.

Scientists are particularly worried about the threat to larger filter feeders, such as sharks, whales and rays. Toxins in the plastics pose a serious health risk to them, they warn. Plastic waste has even reached the Arctic.

A giant build-up of plastic was captured by underwater photographer Caroline Power

So governments and businesses are starting to act.

The UK has committed to eliminating all avoidable plastic waste by 2042, while France has introduced a ban on single-use plastic bags. Norway has been operating a plastic bottle deposit scheme for decades - shoppers receive one krone (9p) back when they deposit a bottle in a collection machine. The UK is considering following suit.

How Norway's bottle recycling scheme works

And supermarkets are trying to reduce the amount of packaging they use, with Tesco aiming for all of it to be recyclable or compostable by 2025.

But one of the problems with plastics is that many are not easily recyclable.

Over in San Jose, California, Jeanny Yao and Miranda Wang, both 23, are focusing on tackling plastics bags and product packaging that is too difficult to recycle.

"Such plastics are heavily contaminated and cannot be recycled by state-of-the-art mechanical recycling," explains Ms Wang.

Miranda Wang (left) and Jeanny Yao are trying to make unrecyclable plastics reusable again

Their start-up BioCellection breaks down these unrecyclable plastics into chemicals that can be used as raw materials for a variety of products, from ski jackets to car parts.

"We have identified a catalyst that cuts open polymer chains to trigger a smart chain reaction," she explains.

"Once the polymer is broken into pieces with fewer than 10 carbon atoms, oxygen from the air adds to the chain and forms valuable organic acid species that can be harvested, purified, and used to make products we love."

More Technology of Business

Helen Bird of charity Waste Recycling Action Programme (Wrap) thinks businesses need to be encouraged to used less coloured plastic, as it's far harder to recycle.

"As a rule of thumb, the clearer the plastic, the greater the opportunity of being recycled into another product or packaging," she says.

Governments need to encourage business to use recyclable packaging and to label it clearly for customers, she argues.

In our throwaway society, there haven't been many financial incentives to develop alternative compostable materials. And the idea that we are suddenly going to wean ourselves off oil-based plastics is fanciful, most experts agree.

"In the next few decades, the global middle class is expected to double," says Ms Wang. "Although we can develop more compostable plastics, there is no way we can stop consuming plastics, which have properties that no other material on earth has."

While awareness of the plastic waste issue is clearly growing, no-one is claiming there's an easy answer to the problem.

Technology of Business will examine how business is reacting to the growing governmental and societal pressure for more sustainable plastics in future articles.

Follow Technology of Business editor Matthew Wall on Twitter, external and Facebook, external