Fukushima's long road to recovery

- Published

Seven years after the disaster, Tepco employees are still trying to repair the damage caused by the nuclear meltdown

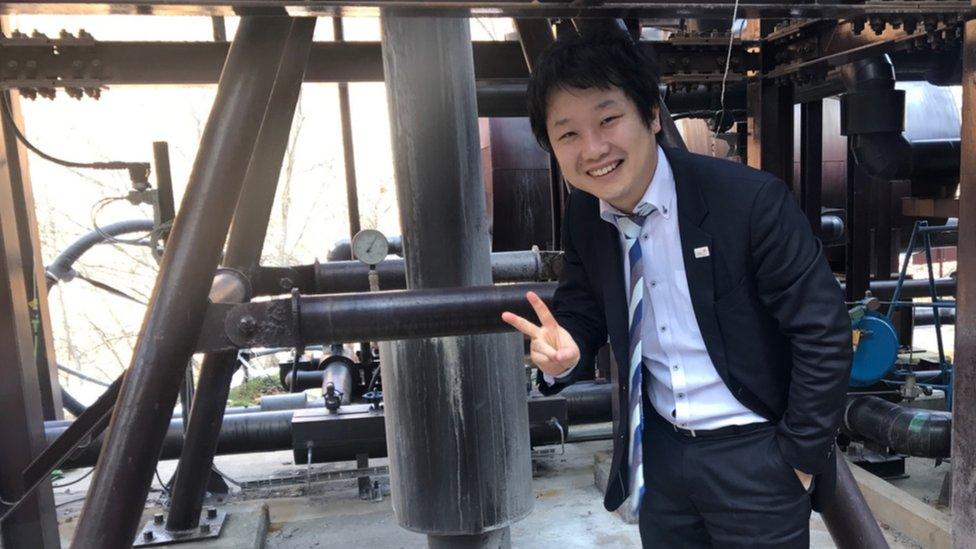

It was supposed to be a day of celebration. But Rio Watanabe's graduation ceremony became memorable for all the wrong reasons.

Mr Watanabe, who was just 23 years old at the time, was in Tokyo when the ground started to shake.

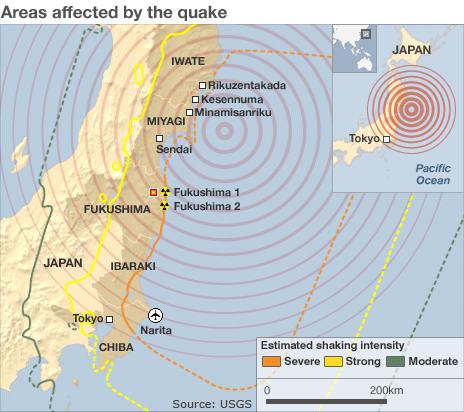

Japan is used to earthquakes. It experiences more than 100,000 of them every year, according to the Japan Meteorological Agency.

But the tremors on 11 March 2011 were so violent that Mr Watanabe thought Tokyo was at its epicentre.

When he realised that they originated 200 miles north of the capital, his thoughts quickly turned to his family in Fukushima, and the Sansuiso Inn run by his father.

The hot spring's location in the mountains meant it escaped the devastation wrought by the magnitude seven earthquake and tsunami which followed.

However, a meltdown at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant sparked fears of contamination, and the spa resort quickly emptied.

Bags of soil that may have been contaminated by the nuclear meltdown line an empty street near the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant

Mr Watanabe still remembers how suddenly things changed. "We suffered heavily after the nuclear blast, and all of our bookings were cancelled."

Seven years on and the hotel's operating profits have not recovered to levels seen before the disaster struck.

Mr Watanabe says: "Some guests still talk about the nuclear disaster. There is still a negative image about Fukushima, and it's been painful for all of us in this community."

The tsunami killed almost 16,000 people and forced the country to rethink its energy policy.

Seven years on and the scars of the 2011 disaster remain. Abandoned houses are obscured by unruly branches and overgrown hedges. Even the vending machines are ignored.

But there are also tales of resilience.

An abandoned vending machine lies abandoned just outside the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant

Mr Watanabe had always planned to return to the Sansuiso Inn in Fukushima to help run the hotel with his father.

He says: "My future was suddenly destroyed and cut off, and I felt so disappointed. It was such as shock."

But the disaster also brought the community together.

Mr Watanabe started working with 'Genki Up Tsuchiyu', which was formed by other hot spring owners in the area.

"Re-energizing Tsuchiyu" is designed to promote activities in the region and bring the community together.

Rio Watanabe hopes that the geothermal plant above the Sansuiso Inn will one day be used to generate power for the entire community

The owners have invested in a "binary geothermal plant" located about 200m above the Sansuiso Inn.

Dozens of intertwining pipes occupy a space about the size of a basketball court, mixing chemicals with steam from the hot spring water to generate electricity.

While most of the surplus energy is currently sold back to the national electricity company, Mr Watanabe hopes a deregulation drive by the government will ensure that the electricity can be used to power the community instead.

He insists that the metal pipes and turbines are a welcome feature of their spa experience rather than an eyesore.

"We've actually shown this to our customers, and the usual reaction is: 'Wow!' They're impressed. They really enjoy seeing this."

Surplus energy is also used to heat giant tanks filled with shrimp on the mountain slope. Farming shrimp is energy intensive, says Mr Watanabe, and those reared here will be sold for a profit

Keeping the lights on in Japan has been an expensive business since the 2011 earthquake.

With few oil and gas resources of its own, Japan expanded its investment into nuclear energy during the 1970s after a 1973 Arab oil embargo sent prices skyrocketing.

By 2010, the country relied on nuclear for 30% of its energy. It had ambitions to raise this towards 50% by 2020.

This fell to almost zero after the earthquake, forcing the country to import vast amounts of gas as reactors were turned off across the country.

Masaru Nakaiwa believes small-scale energy projects like this could be the future for Japan.

The director general of the Fukushima Renewable Energy Institute believes the mountainous terrain and natural hot springs spread over Japan's four main islands make it an ideal place for generators like those seen at the Sansuiso Inn.

He says: "If we want to promote renewable energy in small towns and in the mountains this is a good way without high set-up costs. So it is a very realistic solution to distribute renewable energy nationwide."

While he's optimistic about the role renewable energy will play in all this, he's also realistic about the time it will take to get there.

Opened in Koriyama City in April 2014, the institute was set up to conduct and promote research into renewable energy.

He says: "We have no energy resource, so renewable is our only chance."

A report published by Japan's Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry predicts Japan will still be reliant on nuclear for a fifth of its energy by 2030.

Coal, oil and gas are expected to account for more than 50% of the country's needs, while renewable energy is expected to grow to around 23%, from 3.2% in 2015.

Mr Nakaiwa says: "I think that by 2030 we will still rely on some hydrocarbons, but we are gradually increasing the use of the renewables. But in my opinion we have to decrease our reliance on nuclear and hydrocarbons, so that by 2050 or 2060 maybe 80% of our energy comes from renewables."

While the Fukushima nuclear disaster conjures up images of radiation sickness, loneliness and mental health issues, the struggle to return to normality created the biggest scars of the 2011 earthquake, says Akihiro Yoshikawa.

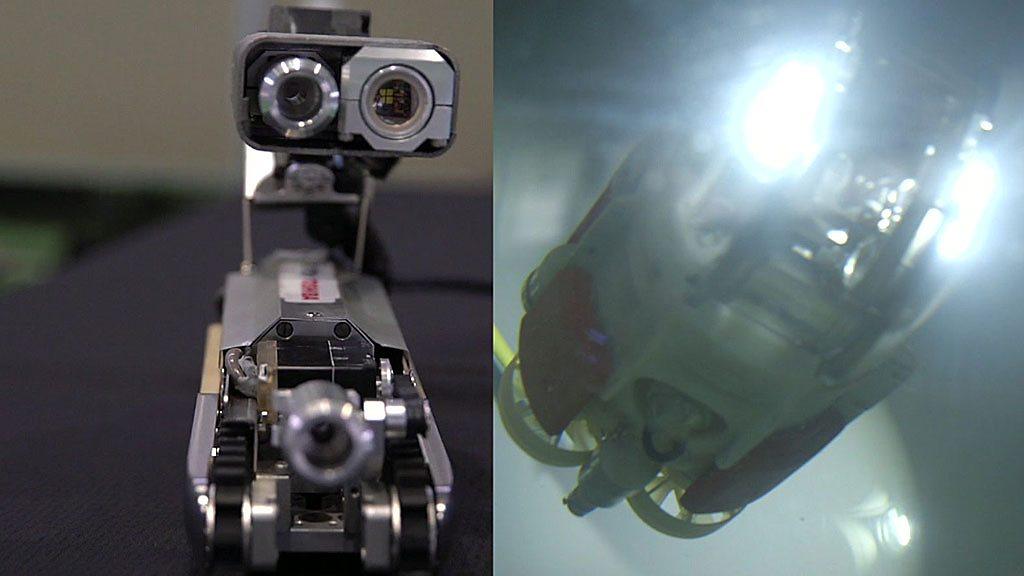

Mr Yoshikawa is a former employee of Tepco, which ran the Fukushima Daiichi Power Plant.

Speaking from Naraha town, which also serves as a meeting point for the community, he says: "I know what it's like to lose everything, that's something we need to talk about. We can also analyse and share what we could lose if something like this happened."

Mr Yoshikawa now spends his time organising tours of the abandoned power plant. He believes sharing information is the key to moving beyond the disaster.

He says: "I always tell them I am still here and I'm not going away, so we can try to build something for the next generation.

"Six years ago people said to me: I want to know but I don't want to go near it. But now they want to know and they actually want to see it with their own eyes. That's the difference."

Akihiro Yoshikawa, who sits with a scaled model of the nuclear plant, uses his knowledge as a former Tepco technician plant to teach visitors what happened in Fukushima

- Published18 October 2017

- Published10 August 2017

- Published2 February 2017

- Published7 March 2017