Should the UK renationalise the railways?

- Published

Is nationalisation the answer for Britain's railways?

Labour wants to bring the railways back under public control - a policy that has garnered widespread support from a travelling public irritated by fare rises, overcrowded trains and a sense that train companies have profited while passengers have not.

The only problem is that about three-quarters of the industry - the track, signalling and big stations - are already under public control.

They were recaptured not by a reforming Corbynist minister, but by the Blairite transport secretary Stephen Byers. When he withdrew support from Railtrack, the privatised owner of the network, in 2001, it collapsed into administration.

From the wreckage was born Network Rail, a not-for-profit organisation whose debts now count as part of public borrowing, and whose budgets and priorities are set in Whitehall.

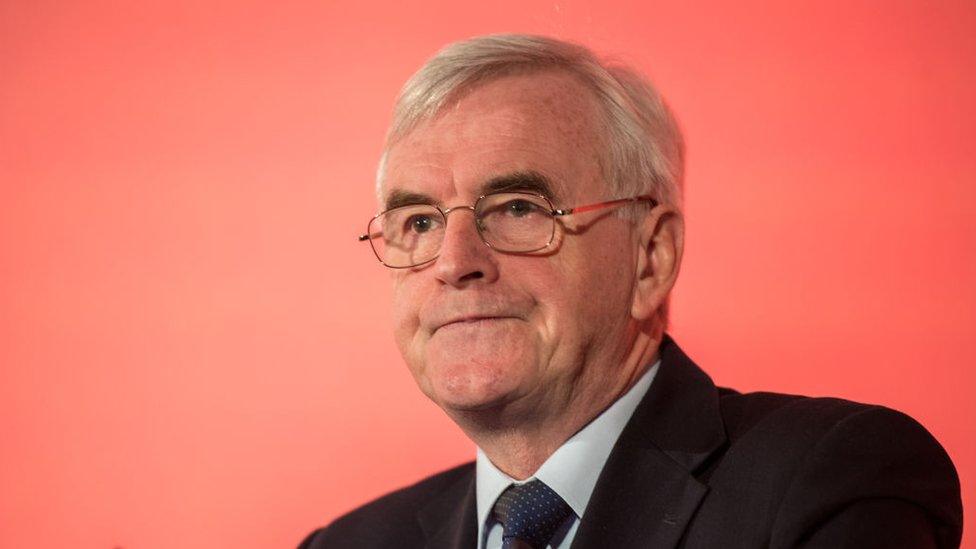

What remains in the private sector are the companies that run the trains - the 25 rail franchises - and the companies that own the trains. When Labour's shadow chancellor John McDonnell talks about a return to public control, he means the former.

John McDonnell says he wants the "the greatest possible integration" for the UK's railways

Mr McDonnell told the BBC in an interview that if Labour were elected it would bring them back in, then reverse the historic split between track and train created at privatisation. He said he would aim for the "the greatest possible integration", claiming it would lead to efficiencies and a better railway. In short, he wants to bring back British Rail.

Those with experience of British Rail and the privatised industry are not as gung-ho as Mr McDonnell.

Michael Holden, the respected executive who was called in to run the government's Directly Operated Railways when the east coast main line went awry in 2007, said the tyranny of the annual budgets hampered British Rail.

"You were always competing for money with education and health. The end result was that we never had enough money," he said.

Would going back to a unified British Rail really solve the railways' current problems?

The private industry has invested more - there are fleets of new trains, and ridership has doubled since privatisation - but the railway still relies heavily on state support.

Even after premium payments from rail franchises are taken into account, the government last year put £3.3bn into the industry, down from £3.8bn a decade earlier. Most of that went to Network Rail as a direct grant.

The cost of improving the railway has also escalated since privatisation. Roger Ford, the technical editor of Modern Railways and a seasoned observer of the industry, said a prime example was the price of electrification - putting in the equipment necessary to run electric rather than diesel trains.

The cost of the latest big scheme undertaken by Network Rail - on the Great Western Main Line - had ended up being roughly six times as expensive as the last similar scheme project done by British Rail. Mr Ford said while some cost escalation was to be expected, "we don't really know why" current costs were so great.

Britain's railways still rely heavily on state support

Paul Plummer, chief executive of the Rail Delivery Group, which industry's umbrella body, said nationalisation "would not help the fundamental issues we face."

Mr McDonnell indicated in an interview with the BBC that a Labour government would be unlikely to try and buy back franchises, offering their owners compensation - the approach he has advocated with a planned renationalisation of water companies - but might instead simply wait for existing franchises to expire.