Are 'cryonic technicians' the key to immortality?

- Published

Technology is changing the way we work and the jobs we do. Will artificial intelligence and robots relieve us of humdrum tasks, making our working lives easier, or will they take our jobs away altogether? As part of our Future of Work series, we look at the cryonics technicians - who are trying to help their clients cheat death.

Are you open minded about the future? Do you have a medical background and can you complete tasks under time pressure?

Are you comfortable working in the presence of a dead body?

This is not the job description for a Victorian grave snatcher.

Instead, it's the ideal attributes of a cryonics technician; someone who preserves the bodies of the recently deceased in the hope they will one day be revived.

Advocates describe it as an "ambulance to the future". They say that as medical science develops, these technicians could become a common sight in our hospitals, purporting to offer believers a second chance at life.

However, most highly doubt it will work.

Buying time

Cryonics seeks to freeze someone after they have legally died in order to keep their body and mind as undamaged as possible. This aims to buy the patient time until future medical science can bring them back to life, and cure them of whatever it is they died from.

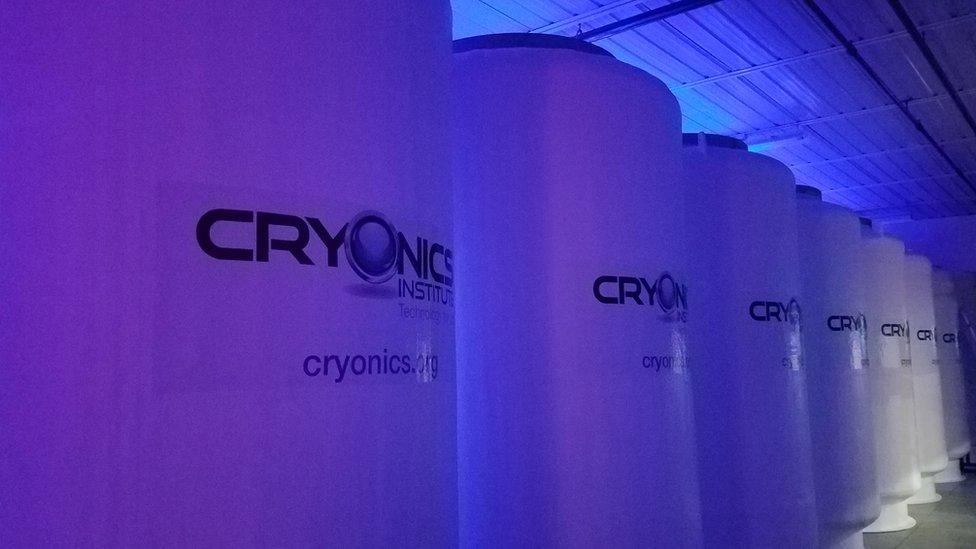

Second chance? Cryonics attempts to protect the body from decay by storing it at extremely low temperatures

As soon as the patient dies, the clock is ticking to start the procedure. The heart has stopped pumping and the brain is no longer receiving oxygen, meaning within minutes it will lose the ability to make new memories, and soon after that the cells will begin to die.

This means the technician must get to work immediately after the individual is declared legally dead, cooling their body in an ice bath in order to slow down the process of degeneration.

Future of Work

BBC News is looking at how technology is changing the way we work, and how it is creating new job opportunities.

After this blood is drained from the body and replaced with cryoprotectant agents - similar to antifreeze - in an attempt to stop ice crystals forming in the blood cells.

The body is then placed in a storage tank and brought down to the temperature of liquid nitrogen (-196C) in an attempt to preserve the organs and tissue.

Necessary skills

While cryonics has been practised since the 1970s, only the US and Russia actually have small storage facilities.

In the US state of Michigan, the Cryonics Institute has about 2,000 living people signed up, and 165 patients who have already gone through the process.

Dennis Kowalski is a paramedic by training, which he says is a perfect fit for the cryonics procedure

Dennis Kowalski is the institute's president and performs some of the cryonic procedures. By day, he is a paramedic.

"The training to become a paramedic is perfect to become a standby in cryonics," he says.

"You also need someone with a funeral director's licence (because you are still legally handling dead bodies), experience running a perfusion pump, and basic surgical skills."

Future role

The Cryonics Institute is a co-operative with just three full-time members of staff, but Mr Kowalski thinks this will grow as medical science evolves.

So far just 5,000 people around the globe have signed up but the numbers are growing so funeral homes may start to offer this as an option, he says.

"Artificial intelligence, genetic modification, stem cell engineering - all these fields are vindicating what we are doing, which is giving people the greatest opportunity possible."

Dr Anders Sandberg has elected to have his head cryonically preserved after death, even though he puts the chance of revival at only 3%

One of the 5,000 is Dr Anders Sandberg, a senior research fellow at Oxford University's Future of Humanity Institute.

He is on the board of the Brain Preservation Foundation and has elected to have only his head preserved after death, even though he estimates a success rate of just 3%.

Like Mr Kowalski, he argues the skills needed to become a cryonics technician are already in use in many medical professions.

"Right now cryonics feels a little too cold or impersonal and it relies on the admission that it is uncertain, but I do think it will grow.

"In the future, wouldn't having a cryogenicist at the hospital make sense? When you do heart or brain surgery you lower the body temperature to buy more time and I imagine that over time we will start doing more low temperature surgery.

"This is a job that you might want to do if you started out as a nurse or a perfusion specialist. It would not be a big leap from a technical standpoint, only from a social one, as it's using arguments from within medicine.

"There's a lot of resistance to overcome but from a practical perspective it makes sense and might save us from a lot of wasteful medicine."

Cryonics and cryogenics

Although they sound similar, cryonics and cryogenics are viewed very differently by the scientific community.

Cryonics specifically relates to the preservation of the human body after death. Most supporters of the process admit they do not know if or when the technology will exist to revive people, or whether the techniques used to prepare the body for storage will have worked.

Cryogenics has many applications in present day medicine, and can be used in stem cell research

Cryogenics, on the other hand, has many applications in today's society. It involves the freezing of matter at temperatures of -150C or lower. In medicine, this includes the freezing of embryos, eggs, sperm, skin, and tissue in order to preserve them for future use.

Clive Coen, professor of neuroscience at King's College, London, suggests applying validated cryogenic techniques to the brain or whole body is doomed to failure.

That's because the application of antifreeze during the preservation process fails to reach all of the brain, and it would be impossible to defrost each part of the body at the same time, he says

"Advocates of cryonics are naive in comparing their wishful thinking with the successes achieved in storing loosely packed cells - such as sperm - at low temperatures.

"And they shouldn't forget that any resuscitation process that isn't instantaneous will merely set the process of decay running again."

Cryogenicists are currently working on freezing other organs

But Prof Coen says cryogenics is an exciting field ripe for expansion.

Although the brain is far too complex, cryogenicists are currently working on freezing other organs. This could revolutionise the process of transplantation, which would no longer have to take place immediately.

"People are tremendously hard at work in this field trying to store organs such as the kidney, and even the heart on a long term basis. That would be a tremendous boon to our health and wellbeing," Prof Coen says.

"But a whole body? Forget it."

Illustration by Karen Charmaine Chanakira