Wanted: Robot wrangler, no experience required

- Published

How about this for a future job advert? "Wranglers wanted for growing fleets of robots. Your responsibilities will include evaluating robot performance, providing real-time analysis and support for problems.

"You must be analytical, detail-oriented, friendly - and ready to walk. No advanced degree required."

Even if this particular advert has not yet appeared, some are already carrying out the role.

Brandon Rees, 32, used to make food deliveries. Now he watches robots do them.

Since September, Mr Rees has been working as a robot operator for Robby Technologies, a Silicon Valley start-up whose robots have been deployed by delivery firms in eight cities in California.

Robby Technologies co-founders Rui Li and Dheera Venkatraman

On a typical day, Mr Rees picks up a robot, then accompanies it through the streets, providing assessment of the robot's performance, back-up in the event of any serious problems, and explanations to curious passers-by.

On other days, he sits at a desk with screens, monitoring the machines from afar.

Mr Rees's role might seem counter-intuitive. After all, robots are widely expected to displace workers - as many as 800 million - or 30% of the global workforce - by 2030, according to one recent McKinsey Global Institute estimate.

We are moving towards having robots doing the physical labour, says delivery firm boss Matthew Delaney

But his job wrangling robots offers a glimpse of the new kinds of roles that are likely to emerge as automation transforms a wide swathe of industries, from transportation to health care.

"The way we view it ... the whole industry is shifting toward the paradigm that we basically have intelligent machines that do the actual physical labour," says Matthew Delaney, chief executive of the robotics company Marble, which started deliveries in San Francisco last year.

"Either in conjunction with a person or where the person is remote support, in more of a manager role."

Paradigm shift

The role performed by Mr Rees is so new it has not even acquired a clearly recognised title.

Job posts use terms like technicians, monitors, handlers and operations specialists. Media outlets have described the role as anything from robot chauffeurs to robot babysitters.

Regardless of the name, analysts say it is clear such positions are growing.

"We use that term 'autonomous' a lot when we think about robots, but in fact very few robots are purely autonomous," says Elisabeth Reynolds, executive director of Massachusetts Institute of Technology's newly launched task force on the work of the future.

"There are always humans someplace, somehow, watching, programming and interacting with them, so I think that's a model that we are going to get more comfortable with and need to get more comfortable with."

Starship Technologies has deployed robot couriers for last-mile deliveries in the US, UK and Germany, among other countries

In addition to Robby, robotics companies such as Marble and UK-headquartered Starship Technologies have advertised the positions, seeking staff to transport robots from warehouses to delivery zones and oversee their activities.

Nor are such plans limited to the delivery sector. Self-driving car companies are also exploring remote command centres.

Some of the demand reflects near-term pressures - such as robots stumped by real-world navigation or local laws that require human chaperones to test new delivery devices.

But executives say they think a monitoring version of the job will remain, even as robots become more independent.

"We will require less and less human assistance but remotely the operators are always behind the scenes," says Rui Li, Robby's co-founder and chief executive.

Customer confidence

Aethon, a Pennsylvania company best known for creating a robot to transport materials inside hospitals, provides an example of what the job might look like at a bigger scale.

The roughly 90-person firm, which has deployed more than 600 robots globally since its start in 2004, has a round-the-clock support centre in Pittsburgh with a staff of 25, many of them hired in the last few years.

The position which involves responding to alerts sent by robots, has existed since the start, but the number of jobs has multiplied in recent years, as the firm's growth accelerated.

"Regardless of how well a robot navigates a particular location, there may be problems that occur," says chief executive Aldo Zini, citing examples like blocked hallways or broken elevators. "We needed to have a way to monitor that."

Robotic welcome: A Cruzr service robot greeting exhibition goers during CES 2018 in Las Vegas

The company - which expects the number of robots it installs this year to increase by 40% - anticipates opening similar facilities in other parts of the world to handle global growth.

"It allows customers to have the confidence that not only are robots going to do their job and do it well, but if there's a problem, we will be on top of it immediately," Mr Zini says.

In a recent report, external, McKinsey Global Institute predicts that new technology will generate between 20-46 million new positions by 2030, while new occupations represent 8-9% of the global workforce.

Robot minding positions - which do not require advanced degrees - have attracted attention amid concerns that most of the new jobs created by technology will be in fields that require significant training, such as engineering.

Whether new occupations will increase in numbers, or with wages, that make up for the positions being displaced is another matter - robot handlers earn about $15-20 (£10-14) an hour at Robby.

Future of Work

BBC News is looking at how technology is changing the way we work, and how it is creating new job opportunities.

McKinsey predicts that the bulk of jobs in future decades will be in fields such as elderly care and construction, where demand is driven by forces such as demographics, rather than automation.

"There's a real robot industry that's growing, but if you look at the overall economy, it's a small percentage," says Michael Chui, a partner at McKinsey Global Institute, the research arm of the consulting firm.

McKinsey says it does not expect automation to drive a large spike in unemployment over the long run, but researchers caution that the forecast depends on how quickly automation transforms the workforce, and how easily displaced workers find new jobs.

The world's robot industry is growing, but it is still a small part of developed countries' economies

Governments will play a role determining that future, through investments in retraining and public policies.

We have already seen instances of public pressure leading officials to press the brakes. San Francisco, for example, recently passed rules that limit where delivery robots can operate. Human pilots are still required on commercial flights, despite autopilot capabilities.

For now, robots remain relatively rare, as Mr Rees's experience on the streets reveals. "People get really excited," he says. "They want to run up and take pictures."

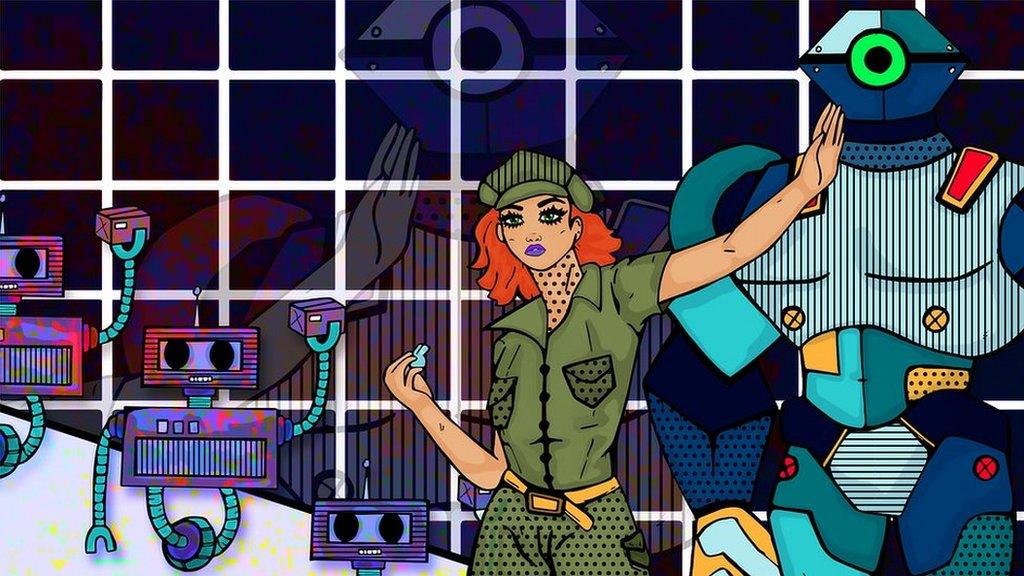

Illustration by Karen Charmaine Chanakira

- Published11 September 2015

- Published7 December 2017

- Published15 October 2017