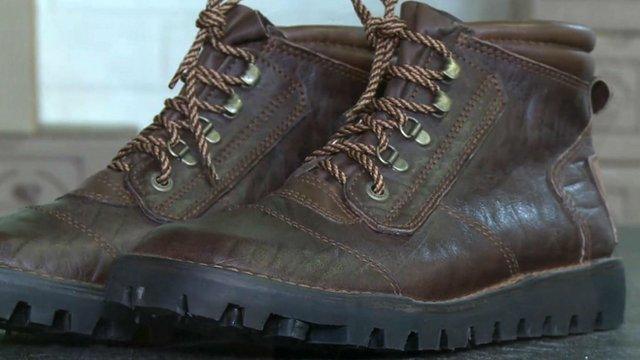

Making boots from hippopotamus and ostrich

- Published

The Courteney Boot Company makes just 18 pairs of shoes per day

The air is heavy with the pleasing smell of new shoes as a team of 16 craftsmen slowly and studiously make safari boots.

With each pair taking two weeks to produce from start to finish, you can never accuse the Courteney Boot Company of rushing things.

Instead the business, one of the world's most exclusive footwear brands, currently makes just 18 pairs of handmade boots and shoes a day.

Founded in 1991 in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe's second city, Courteney continues to be a rare business success story in a country whose economy has struggled greatly over the past 20 years.

Using exotic game skin leathers such as crocodile, buffalo, hippopotamus and ostrich - all from Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora approved and renewable sources - its boots remain much in demand around the world.

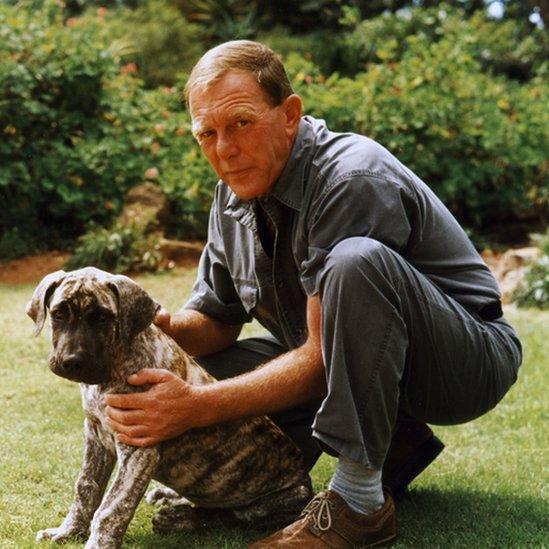

Gale Rice has led the business on her own since 2012 following the death of her husband, John

The company was set up by husband and wife team John and Gale Rice.

John had started making shoes in the UK in 1953 when aged 15 he began working for British shoe company Clarks. His career then took him to South Africa, before moving to Zimbabwe.

The couple ran the business together for 21 years until John died in 2012. Since then Gale has led the company on her own.

Looking back on the early days of Courteney she says that she and John devised a novel way to promote the business.

"Right at the beginning we made boots for all the well-known safari operators in Zimbabwe and South Africa free of charge, and delivered most of them ourselves," says Gale.

"The safari operators would wear the boots while out in the bush with their overseas clients, and they promoted us - word of mouth."

The company employs 16 people

The holidaymakers would then find shops in Zimbabwe and South Africa to buy their own pairs of Courteney boots to take home with them at the end of their vacations. In turn they would recommend them to their friends, who would place orders from overseas.

Zimbabwe's large commercial farmers, typically white Zimbabweans, also became enthusiastic purchasers of the boots.

Gale adds: "We had three main customers - the hunter, the farmer, and the tourist."

The company grew strongly until the economic and political meltdown that started in Zimbabwe in 2000 saw the company lose most of its local customers. First, many of the white farmers left the country, and then tourist arrivals declined sharply.

To survive Gale focused on increasing exports, which rose from 50% to today's 85% of total sales.

The company takes its name from 19th Century British explorer Frederick Courteney Selous

"From the very beginning we always intended to try to make our boots available to our niche market all over the world," she says.

"And it is just as well that we did have that strategy. Since 2000 Zimbabwe has deteriorated to almost the brink of collapse.

"For sometime now it has been the case - export or die."

With global stockists including gun companies such as John Rigby and Westley Richards, Gale says that 70% of its sales are now via the internet, with 20% of that amount via Courteney's own website.

Every pair of its $145-492 (£105-355) boots and shoes are made to order at the company's small workshop, and Gale says that the company will never increase production above 30 pairs per day, so as to maintain quality control. "I absolutely follow that strategy," she says.

The company doesn't rush to make its boots

"I would say there are several factors to our exporting success, but by far the most important is concentrating on making the best, most comfortable, and durable boot possible.

"Most of our attention goes on getting the product right."

Explaining the fact that everything is made to order, she adds: "We are manufacturers not retailers.

"We can't tie up capital by keeping stock, and especially not every style, in every leather, in every colour."

Fungai Tarirah, a portfolio manager at South Africa-based investment fund Rudiarius Capital Management, says that a key issue any Zimbabwean company has to overcome is the fact that the country is landlocked.

This is the latest story in a series called Connected Commerce, which every week highlights companies around the world that are successfully exporting, and trading beyond their home market.

"A fair amount of the challenges faced by Zimbabwean-based exporters are around the fact that the country's a landlocked country, so if your customers are halfway across the world you essentially have to deliver the goods in two legs.

"That sometimes triples or quadruples the amount of paperwork that one has to deal with - but also the lead times."

Thankfully, Mr Tarirah adds that at the same time the internet has been a "game changer" for exporters from countries like Zimbabwe.

"It is now a lot easier for manufacturers to produce in a 'just in time' fashion, as opposed to building up stocks that may or may not move over the next three, six or nine months.

"It allows them to reach larger further-flung markets which they normally could not have accessed."

John Rice had made shoes since he was 15

Gale says that "without a doubt our secret to being a successful exporter is attitude".

She adds: "Shipping overseas seamlessly takes a lot of communication and patience and attention to detail."

While domestic sales are slowly rising again since former president Robert Mugabe resigned back in November, Gale says it is still not easy to be a business in Zimbabwe.

"Life is very difficult here, but we choose to focus on the positive and keep our heads down. We know what we have to do."

- Published22 July 2016