Spring Statement: Why is the chancellor so upbeat about the economy?

- Published

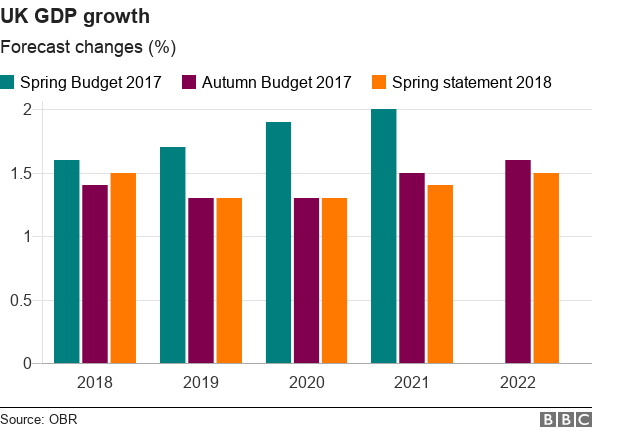

Philip Hammond says economic growth forecasts have been revised.

Chancellor Philip Hammond predicted a bright future for the UK in his first Spring Statement - but why was he in such an upbeat and jovial mood?

Well, Mr Hammond reported a higher growth forecast for 2018, and a fall in inflation, borrowing and debt.

He told MPs: "We have made solid progress towards building an economy that works for everyone."

What did he say about borrowing?

Mr Hammond said borrowing was due to fall in each of the next few years, with the 2017 figure of 2.2% of GDP predicted to drop to 0.9% in 2022.

As a result, debt as a percentage of GDP is predicted to go down every year up to 2022 - the first sustained drop in 17 years.

"That is a turning point in this nation's recovery from the financial crisis a decade ago," said Mr Hammond. "There is light at the end of the tunnel."

The OBR says inflation will fall to 2% by the end of the year - in line with the Bank of England's target.

What's the story on economic growth?

Mr Hammond said the economy had grown every year since 2010, adding that the Office for Budget Responsibility had confirmed growth of 1.7% was achieved in 2017, higher than its 1.5% forecast in last autumn's Budget.

The OBR also revised its growth forecast for 2018 up to 1.5% from 1.4%

One reason in the short term for the rise in economic growth is a robust global recovery.

The stronger expansion in 2017 also meant the economy carried more of that momentum into 2018.

While productivity growth over the last two quarters is the strongest since the 2008 recession, this is not expected to translate to higher growth in later years.

Output per working hour rose by 0.8% in the three months to December following a 0.9% rise in the previous quarter, according to the Office for National Statistics.

The OBR's growth forecasts for 2019 and 2020 remained unchanged, while those for 2021 and 2022 were reduced slightly.

Will the chancellor now spend more?

It is a possibility.

Despite revealing the smallest budget deficit since 2002, Mr Hammond had already said the national debt was too high and that it would be wrong to put "every penny" into more public spending.

However, he said that if public finances continued to reflect current improvements by the autumn, then he "would have capacity to enable further increases in public spending and investment in the years ahead".

Ian Stewart, chief economist at Deloitte, said: "These forecasts put the UK in a better position to face the moment of truth on Brexit.

"The decision phase of the Brexit talks will shortly be upon us. Stronger public finances give Mr Hammond more firepower to support the economy if the Brexit talks don't go according to plan."

However, he added: "We should not get carried away. These forecasts are likely to be no less fallible than earlier ones and, despite an improving trend in public borrowing, the burden of debt in the UK is still at its highest in over 50 years."

What did the fiscal watchdog say on Brexit?

The OBR spelled out for the first time the likely cost of the Brexit divorce bill.

It estimates the total cost of the financial settlement with the EU will be £37.1bn.

Most of this - about £28bn - is due over the next five years. However, pension promises mean the UK will still be paying around £2.5bn all the way to 2064.

The OBR also estimates that Brexit will free up around £3bn a year to spend on other things by 2020-21, rising to £5.8bn in 2022-23 after taking account of "financial settlement transfers".

It assumes that this money will be recycled into extra spending, rather than used to pay down the deficit.

However, it warned that this so-called dividend should not be viewed in isolation.

It said: "While this is one of the more direct ways in which leaving the EU impacts upon the public finances, it is unlikely to be the largest one."

The watchdog estimated in November 2016 that a combination of weaker productivity growth, lower net inward migration, and higher inflation would push up borrowing by about £15bn a year by the start of the next decade.

The government has also signalled that it is willing to pay to remain part of some European regulatory agencies after Brexit, and areas such as science and education.

The OBR said spending in these areas was around £7bn a year.

The Treasury asked the watchdog not to factor this into its calculations because it said "final decisions" on spending had not been made.

Is the UK in a good place compared to other countries?

Not really, according to Paul Johnson, director of the Institute for Fiscal Studies.

He told the BBC: "The growth forecasts are about 1.5% growth each year for the next few years which is better than forecasting a recession, but it's an awful lot worse than you might reasonably expect.

"We've got used to growth of 2 to 2.5% a year since the last war really and if you actually look at what other economies around the world are doing, they're mostly doing quite a lot better than the UK economy.

"So overall the British economy is sluggish at best. That means our living standards will grow very slowly at best - it looks like 'not very good' is the new normal."

- Published12 March 2018

- Published13 March 2018

- Published13 March 2018