A pension of £18,000 - or £1,000? The auto enrolment dilemma

- Published

Employees on the Wiston estate are among those facing a pensions dilemma

Since auto-enrolment pensions began in 2013, the average employee has only been paying in a few pounds every week.

But from 5 April, contributions will rise dramatically.

Workers will need to decide whether to contribute hundreds of pounds extra into their pensions every year or opt out of auto-enrolment altogether.

Figures calculated for the BBC suggest it could make the difference between earning more than £18,000 a year in retirement, or as little as £1,000, on top of the state pension.

Many workers may decide they cannot afford to pay the extra.

It is such a serious dilemma that one expert has called it "auto-enrolmageddon".

Here we explain what the changes will mean for the nine million workers in auto-enrolment.

How much extra will I have to pay?

By the time a second round of changes comes into effect in April 2019, the average worker will be paying an extra £700 a year into their auto-enrolment pension, according to the stockbroker AJ Bell.

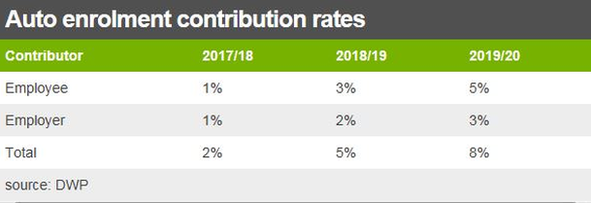

Until now, employees have been paying just 1% of their qualifying wages into their pensions. This is made up of 0.8% from the worker, plus 0.2% in tax relief from the government.

For someone on an average £27,000 salary, that has meant annual contributions of about £169.

But this April, that will rise to a minimum of 3%, or £517 on average.

In April next year, the employee contribution rate will go up to 5%, or £876 a year.

What if I want to opt out?

If you don't want to pay the increase, you have two options.

You can opt out altogether and stop making contributions.

Or you can "opt down". This means you continue to contribute 1% of qualifying earnings. The downside of this option is that, under the rules, your employer is no longer obliged to make his or her contribution.

Steve Webb, policy director of Royal London and one of the architects of auto-enrolment when a pensions minister, urges people to consider the importance of getting "free money" from their employer, as well as the tax relief.

"If you give up on that contribution early in your working life, the cumulative impact could be enormous," he says.

"It could be the difference between enjoying a comfortable retirement, or being forced to work on past traditional retirement ages because you cannot afford to retire."

The employee

Beth Fryer is a 22-year-old assistant gardener on the Wiston Estate in West Sussex.

Up to now, she has been paying 1% of her income into her pension, amounting to just under £10 a month. From April, her contributions need to rise to 3%, or just under £30 a month.

Since she is saving for her first home, she is not sure whether she can afford the extra.

"A pension seems so far in the future," she says.

"What I'm going to need sooner is a deposit for a house, rather than that money from the pension.

"But I also know that the money does add up, and if your employer is matching what you put in, then that is a really good thing to have."

After talking to work colleagues, she thinks she will at least opt in for a while, even if she has to rein in her spending.

The employer

Richard Goring manages the Wiston Estate, a family-owned business since 1743.

If any of his 22 employees did opt out of auto-enrolment, he would no longer have to make a 1% contribution.

But persuading them to do so is against the law.

In any case, he is a big supporter of pensions. He offers even more generous terms than the rules dictate, offering to match worker contributions up to 12%.

"Our salaries are not huge in comparison to other sectors, and so we wanted to make sure that people were getting a decent amount of pension from us," he says.

He is particularly keen to make younger employees aware of compound interest, which has a huge multiplying effect if you start saving early.

"I would be saying, 'Go for it, guys, because the more you put in now, the bigger difference it's going to make later on.'"

How much extra will I get for staying in?

This is difficult to calculate, because no one knows how much they are going to earn in the future or how the stock market will perform.

In addition, contribution levels are likely to change further.

At the moment, only earnings above £5,876 automatically qualify for auto-enrolment, but the government is planning to allow all wages to qualify - which would boost pension pots, and contributions, considerably.

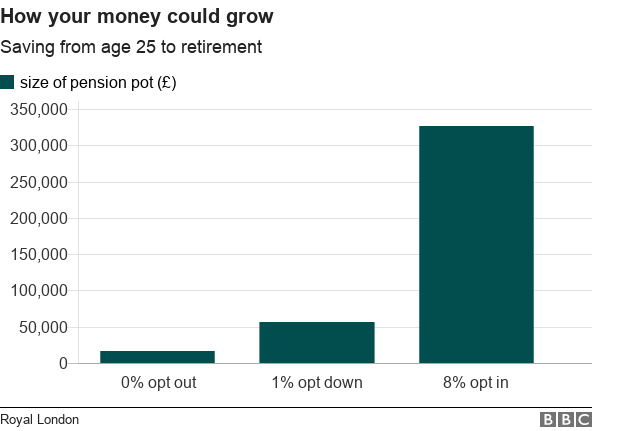

Assuming that happens in the near future, the insurance firm Royal London calculated the possible size of a worker's eventual pension pot.

To start with, it looked at someone who starts saving at the age of 25, on the average salary.

With combined contributions of 8% a year, it believes that person could achieve a pot of £327,000 by state retirement age. (See chart above).

If they opt down - and pay in just 1%, with no employer contribution - that pot would only grow to £56,000.

Assuming they stop paying in altogether - after five years of saving - they would have just £16,000.

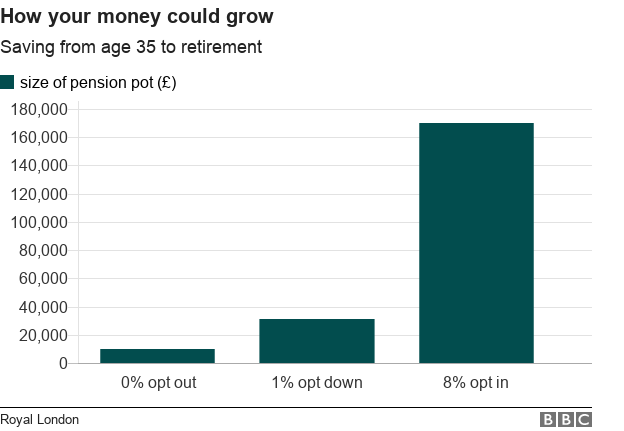

Someone who starts saving at the age of 35 will end up with a much smaller pot.

With 8% contributions until retirement, their pot could grow to £170,000. By opting down, they would only have £31,000. Or just £10,000 if they opted out altogether.

Some critics say such figures are speculative, and should not be relied upon.

What income can I expect in retirement?

As in all Defined Contribution (DC) schemes, auto enrolment workers end up with a pension pot, with which they can finance their retirement.

One option is to use it to buy an annuity, or income for life.

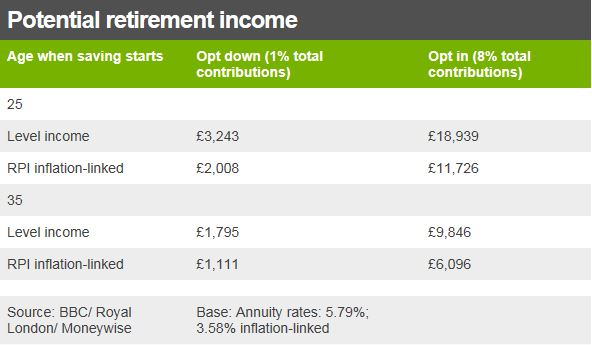

Assuming that a worker uses the whole pot - disregarding the 25% tax-free lump sum - we calculated that a 25-year-old who remains opted in can expect an annual income of up to £18,939 at the age of 65.

This would be for an annuity that does not rise with inflation.

Should that worker opt down in April, they could expect an income of just £3,243.

Similarly, a 35-year-old could expect an income of £9,846 by the age of 65, if they remain in the scheme for 30 years.

If they opt down, they would merely receive £1795.

How many will opt out?

So far under auto-enrolment, about 9% of workers have opted out - far fewer than the government expected.

The industry expects that proportion to rise over the next couple of years.

But many experts think the numbers will be limited.

"We don't expect there to be mass opt-outs, because people know they should be saving towards their retirement," says Andy Tarrant, head of policy at The People's Pension, the second largest provider.

In a recent policy paper, Royal London argued that wage increases in April will also disguise the extra contributions required.

Do I have to do anything?

Unless you tell your employer you wish to opt out or down, your contributions will automatically increase on 5 April, and in April 2019.