Baselworld: The watchmakers keeping Switzerland's traditions alive

- Published

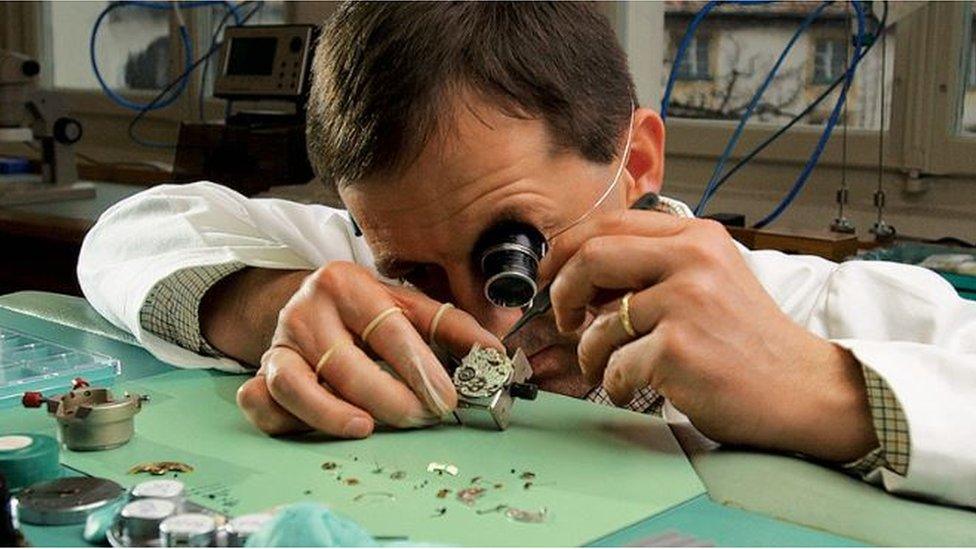

The Voutilianen workshop can spend years designing and hand-making watches for collectors.

There's a separate area inside the world's biggest watch fair where the showbusiness and champagne is less conspicuous.

The huge Baselworld arena, in the Swiss city of Basel, is this week hosting a catalogue of 'A' list celebrities to add glitter to the latest product launches from the big luxury brands.

However, you're unlikely to find Usain Bolt or Colin Firth at Les Ateliers, a quieter quarter of the six-day event where many smaller, independent watchmakers reveal their wares.

But you will find men like Kari Voutilainen, who produces about 50 wristwatches a year which sell for tens of thousands of pounds - minimum - and take years to design and make.

Les Ateliers is also a place for the avant garde.

Maximillian Busser & Friends (MB&F) makes what it calls miniature machines, many of which, says director Charris Yadigaroglou, have no "rational reason" to be built other than to demonstrate the beauty and craftsmanship of watchmaking.

Sales slump

Major players such as Swatch Group, Tag Heuer, and Rolex dominate Swiss watchmaking - and will dominate Baselworld.

But the country still has scores of independent watchmakers turning out precious pieces for collectors and enthusiasts.

And with Switzerland's watch industry suffering a sales slump in recent years, many firms have struggled.

It's important that the country's independent sector thrives, says Jean-Daniel Pasche, President of the Federation of the Swiss Watch Industry.

They are not just a source of skills, training and innovation; they are a link with Switzerland's watchmaking heritage dating back hundreds of years.

"The independent sector adds to the richness of the industry," Mr Pasche says.

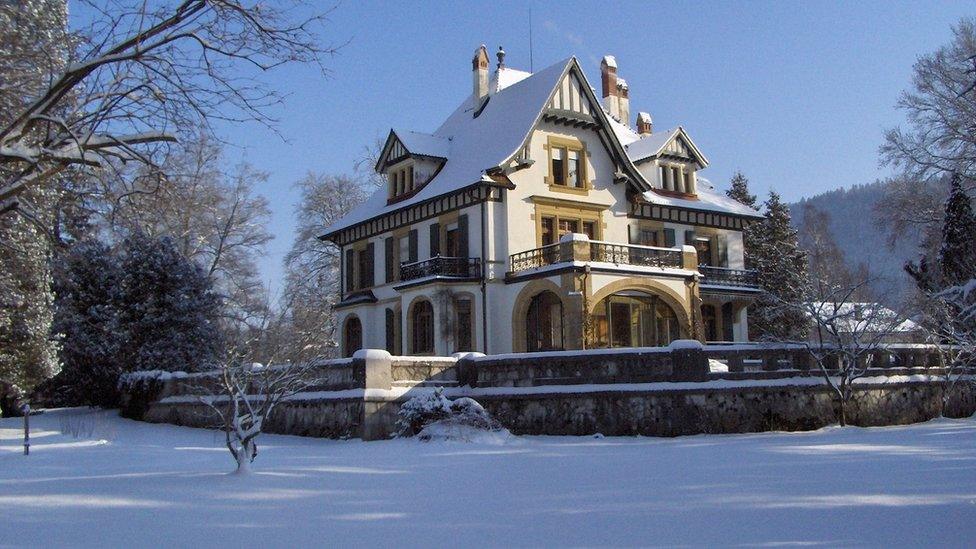

Like many small independent watchmakers, the Voutilainen workshop is in a rural part of Switzerland

Mr Voutilainen, born in Finland in 1962, wanted to be part of this heritage, and came to Switzerland in 1988 to learn his trade.

He's been fascinated by the mechanics and detail of watchmaking since childhood, and is now regarded as one of the world's foremost experts in the field.

Slow time

Made to order, his pieces have a starting price of about 72,000 Swiss francs, rising to about 360,000.

The watches nod to a classical style of design. "I do not like geometrical forms, I like soft curves," Mr Voutilainen says. "I like vintage cars - a Jaguar E-Type or old Maserati. They are just stunning.

"Designs today are industrialised. Sometimes, a product looks too perfect because it's machine-made."

In his workshop at an old house in an idyllic rural setting in the Motiers district, Mr Voutilainen and his 22 staff design, fabricate and assemble timepieces.

No parts are bought in. Everything from the tiniest screw, the dials, and the movements - the beating heart of a watch - are made in-house.

But even someone as renowned as Mr Voutilainen faces challenges in a changing industry. The big labels have grown through takeovers and mergers. Their global marketing clout gives them huge power.

"This bigger industry is, for us, the biggest challenge to finding customers," Mr Voutilainen says. He has no marketing budget or communications team, and carries no stock at his workshop.

And he is strict about spending at least 60% of his time making watches, lest he lose sight of his reasons for setting up as an independent watchmaker.

He says: "There is an ever-lurking danger that you become a manager and are never behind the bench anymore. The product will suffer, and within the shortest time you have sold your soul to the devil."

MB&F creates watches - and then tries to find customers to buy them

But buyers must be patient, as time is not something Mr Voutilainen will rush. A "simple" watch takes about 12-14 months to produce. "For more complicated pieces, it may take three, four, five years," he says.

Concept watches

Staying true to the craft can be difficult, however, when bigger brands can get products to market more quickly and cheaply.

MB&F's Mr Yadigaroglou says the independent sector is suffering as the big brands expand. "It was big is beautiful. Everything could be done in-house," he says.

"But some of the skills were so specialist, it was not practical to do it all in house. So they made suppliers sign confidentiality agreements about who they worked for."

MB&F has a different business model. The word "friends" in the company's name - Maximillian Busser & Friends - refers to the independent artisans it uses.

The company has a core staff of 20, but a network of specialists for specific projects. "Most are Swiss, but we did once go to South Korea to get a particular bezel on one piece," Mr Yadigaroglou says.

MB&F produces about 300 watches a year, and does not make-to-order. "We start with the concept - something that we think is cool," Mr Yadigaroglou says. "Then we try to find a buyer. It's a risky way of doing things."

Paul Picot wants to double production to 10,000 watches a year

Paul Picot is a specialist in enamelling the watch dial

Arguably, the firms facing the biggest challenges are those independents just snapping at the heels of the bigger brands.

Whereas Voutilainen or MB&F make strictly-limited pieces for a select few, the family-owned firm Paul Picot is trying to double in size in order to compete.

"I think we have a quality comparable to international high-end brands," says chief executive Massimo Rossi. But he doesn't have their brand and marketing power.

Paul Picot sells about 5,000 watches a year, with a core price bracket of between 2,000 and 10,000 Swiss francs (£1,500-£7,500).

But for something more complicated - the firm is becoming a specialist in enamelling designs on the dials - the price can easily rise to about 40,000 francs.

But Paul Picot is neither exclusive enough to charge tens of thousands of francs per watch, nor big enough to compete with more powerful brands.

"We need to grow," Mr Rossi says. "5,000 pieces is not enough. We would like to go to 10,000 pieces. But even that is still very limited for the price range we are in."

The company buys in most of its watch parts, leaving its 12 employees to concentrate on design and creating specialist pieces. "For our watch price, it's just not viable to produce everything in house," Mr Rossi says.

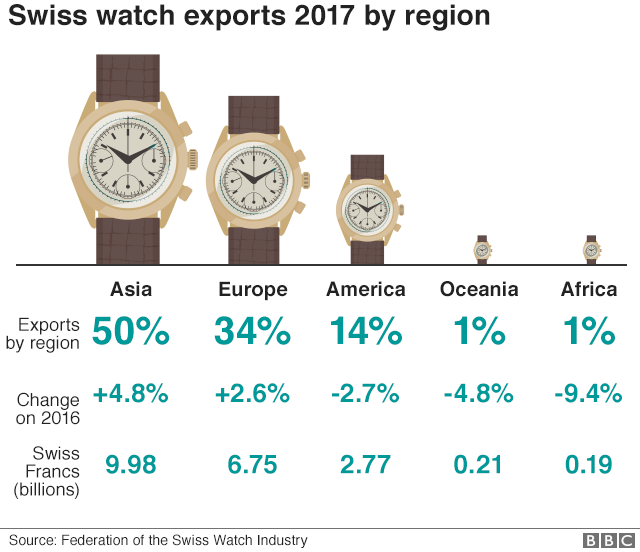

Despite the constraints, he says it's a good time to think about expanding the firm. The industry's sales slump looks to be over, according to figures released this week by the Swiss Watch Federation., external

Swatch Group, Switzerland's biggest watch company, returned to profit last year and is bullish about 2018.

"I hope worst is over. I'm convinced things will start to become better," Mr Rossi says. The big brands always recover first: "With luck, the independent watchmakers will not be far behind them."