A pair of glasses to see a better future

- Published

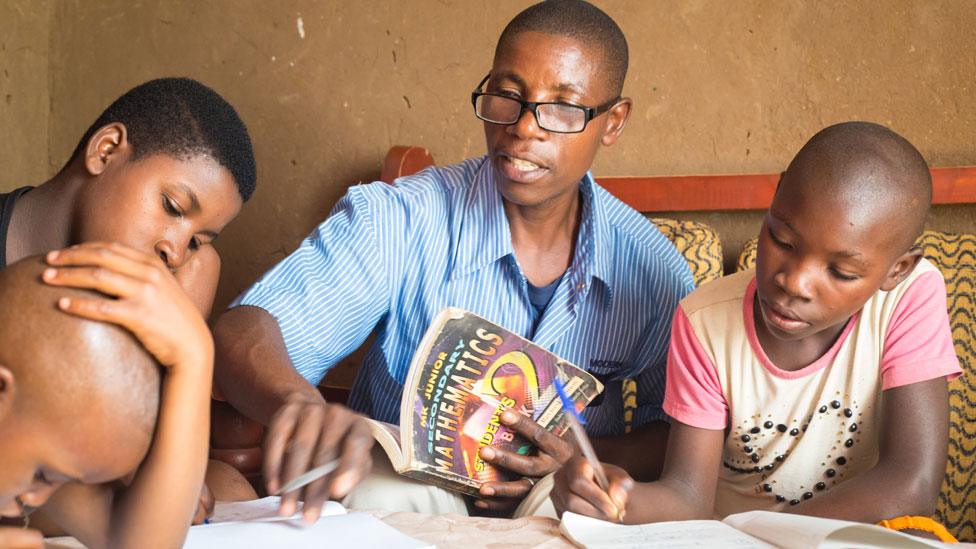

The lack of affordable glasses can be a barrier to learning and earning for billions, says the report

The turning point might be that moment when you're struggling to read the small print of the cooking instructions.

Or else it might be when you're straining to read messages on your mobile phone or decipher a map - and have to hold them further and further away, screwing up your eyes to see.

It's the moment when you realise you need to do something about your sight, which might mean a trip to the opticians or buying a pair of reading glasses in the chemist's or supermarket.

But what would happen if there was no way of getting help? What would the consequences be if there were no opticians or affordable glasses and you simply had to accept not being able to read?

The chances of keeping a job or staying in education would begin to diminish, even if it was only a minor problem that could be corrected by glasses.

Narrowing opportunities

A report this week from the Overseas Development Institute shows how much can be lost by something as simple as the absence of a pair of spectacles.

If children cannot see well enough to read, they can be trapped in poverty

There are an estimated 2.5 billion people worldwide who need glasses but do not have access to them. About 80% of these are concentrated in 20 developing countries, mostly in Africa and Asia.

The report says that the most acute lack of access to eye care and glasses is in the most disadvantaged communities, marginalising even further those with vision problems.

Poor sight in poor countries, says the report, is a barrier to education and employment. It traps families in poverty.

And the ODI think tank warns that while aid budgets are given to urgent, life-threatening illnesses, relatively little international attention is paid to the slow-motion disaster of someone struggling to see clearly.

Locked in disadvantage

But not being able to see well enough to read, and not having glasses, "can lock children into a life of disadvantages", says the ODI report.

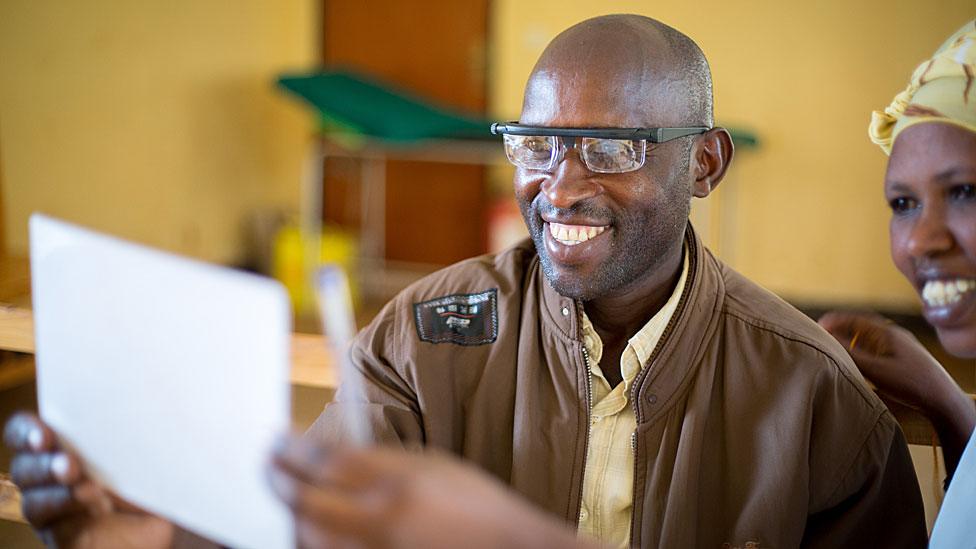

A pair of glasses can help people to read and be able to work

They can be seen as low achievers and fail to get qualifications, rather than be seen as having a simple problem that could be rectified.

Among adults, researchers say, vision problems can mean loss of opportunities in work and loss of income - and for the local economy a lowering of productivity.

The report was commissioned by Hong Kong businessman and philanthropist James Chen, who has made improving eye care something of a personal mission.

He founded a charity in Rwanda, Vision for a Nation, that has tested ways of delivering eye care to large numbers of people.

Taking the long view

Nurses have been trained to give eye tests, glasses have been provided at low cost or for free and there have been treatments for some eye problems, such as eye drops for conjunctivitis.

Being able to see clearly makes a big difference to individuals and local economies, says the report

The Rwandan project has reached two million people and has delivered 160,000 pairs of glasses.

Mr Chen's charity, Clearly, is lobbying for more attention to be paid to eye problems and to make glasses more readily available.

"Glasses have been manufactured in different parts of the world for at least 700 years, but at least a third of the world's population still do not have access to them," says Mr Chen.

"Most of these people have easily correctable problems such as short- and long-sight. The cost to their quality of life is huge and the total economic cost throughout the world runs into the trillions each year."

Economic gains

He wants the Commonwealth heads of government, gathering in April, to make sight problems and access to glasses a priority in development projects.

The report says that the economic returns are far greater than the costs of eye tests and glasses

Mr Chen says this is a deceptively simple way of improving individual lives and benefiting national economies by making people more productive.

He says that within Commonwealth countries, making glasses available would mean an economic boost worth $44bn (£31bn) per year.

Former UK Prime Minister and UN education envoy Gordon Brown has backed calls to do more to tackle "the cost, in human and economic terms, of so many of our fellow citizens being unable to see".

"If we fail to act, those left behind will never catch up," Mr Brown says.

The ODI report suggests the economic return can be 30 times greater than the cost of glasses and the eye-care screening.

Elizabeth Stuart, of the development think tank, said: "If a third of the world cannot see clearly, and fixing it requires only limited investment, and delivers excellent returns, then this would seem to be a no-brainer."

She said giving people better vision would help to improve education and eliminate poverty - for people who would otherwise be left behind.

More from Global education

The editor of Global education is sean.coughlan@bbc.co.uk