Can Fitbit get itself back into shape?

- Published

James Park co-founded Fitbit in 2007

When James Park bought a Nintendo Wii back in 2006, little did he know that the purchase would plant the seed for the birth of his own global technology brand.

Trying out the games console for the first time at his home in San Francisco, the then 29-year-old was greatly impressed by the motion-sensor technology that allowed users to control their on-screen avatar with body movements.

"Wii made exercising a fun and positive activity that the whole family could do together, that was very striking for me," says Mr Park, now 41.

"I thought, how can I capture this magic and make it portable?"

His idea was to create a wearable fitness tracker, and in April 2007 he and friend Eric Friedman founded a company called Fitbit.

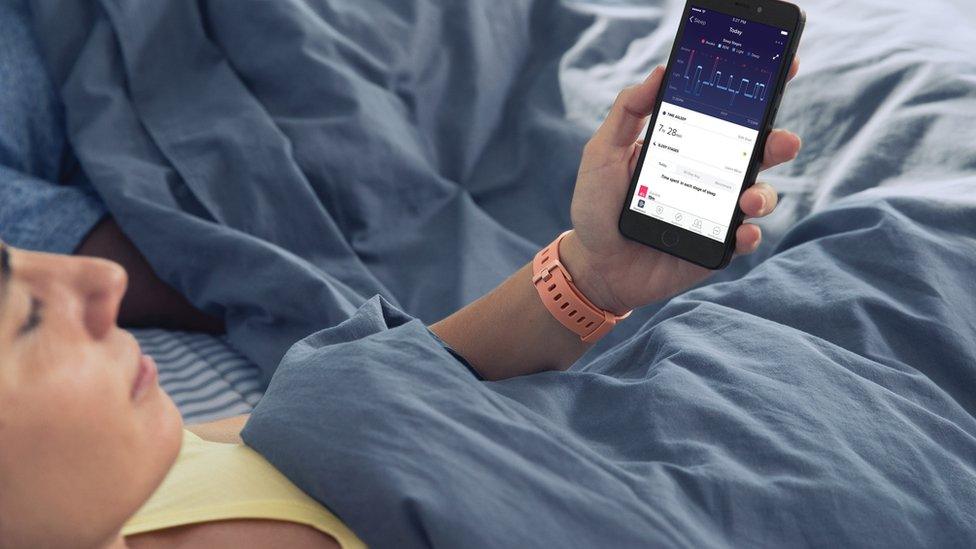

Today the San Francisco-based business sells more than 15 million devices a year - wristbands and watches that record a user's heart rate, the number of steps they have walked, and other exercise statistics.

Yet the firm has faced tough times lately. Demand for fitness trackers has cooled, at the same time as Fitbit has faced increased competition from the likes of the mobile phone giants Apple and Samsung, which have brought out their own smart watches.

As a result, last year Fitbit saw its annual sales fall by almost a third, external to $1.6bn (£1.1bn), while losses more than doubled to $277m.

Mr Park, who has the chief executive title, is confident that he can turn things around, as the company expands into the healthcare sector.

Fitbit makes fitness trackers and smart watches

Mr Park developed his passion for technology as a teenager growing up in Cleveland, Ohio, where he learned to code using programming languages like Basic and Pascal.

He says he loved taking computers apart and putting them back together again.

"I gravitated to computers because I knew I liked what I was seeing," Mr Park says.

After he finished high school he started a degree in medicine at Harvard University, but soon dropped out to work at investment bank Morgan Stanley.

However, finance didn't appeal either, so he left and started his first tech start-up in the late 1990s, at the height of the then dotcom boom.

The business, which specialised in e-commerce transactions, flopped in 2001, and so Mr Park started another firm with Eric Friedman, who is today Fitbit's chief technology officer.

Their venture, Wind-Up Labs, created tools for digital photo editing and photo sharing. It quickly attracted the attention of CNET Networks, a Californian technology media group, which acquired it for an undisclosed sum in 2005.

"That acquisition gave me my first real look at how a big technology firm operates," says Mr Park, who joined CNET for two years after the deal. "It was a formative experience for me because I learned how executives manage teams, how to lead people."

Fitbit users can compete against each other online

After his Nintendo Wii epiphany, Mr Park quit CNET and started working with Mr Friedman on Fitbit.

With only a small team behind them, Mr Park had to spend "many days and nights" programming the firm's software platform by himself.

He and Mr Friedman also toured Asian factories to learn about manufacturing their tracking devices.

"Eric and I were software engineers not operations people, so we needed to find out how to build hardware in a short span of time," says Mr Park.

In the mid-2000s, fitness fans were using low-end pedometers to track their steps, but nothing truly digital had come to market.

However, when Fitbit launched it filled a gap in the market and grew fast.

The success of the company was helped by the development of its app, which enabled users to connect and compete with each other online.

"We saw how the social aspect of Fitbit motivated people to exercise," says Mr Park. "We found that every friend you add to your Fitbit community increases your steps-per-day by 700."

Fitbit grew fast and it listed on the stock market to much hype on 17 June 2015. Its shares reached a peak of almost $50 in July 2015, but they are now trading around the $5 mark.

Fitbit now faces fierce competition from smartwatch makers such as Apple

Ramon Llamas, a technology analyst at research group IDC, says that Fitbit needs to expand what it offers its customers in order to better compete.

"Fitbit collects immense amounts of data on how people get fit, but what else can you do with that data?" he says.

"If I was a Fitbit user, I'd want insights and advice that can help me. But they aren't providing that."

Mr Park says he is confident of Fitbit's continuing place in the fitness tracking sector.

"No single company will win the space of using digital tech to help people get motivated to be healthy," he says. "There will be multiple winners and we're fine with that scenario."

The firm does need a win in 2018 though, and in March it unveiled a new smartwatch called Versa. A simplified, less expensive version of previous models, it has earned praise from gadget reviewers, and may help Fitbit recover some lost market share.

At the same time, it is continuing to expand into the healthcare industry.

This year Fitbit invested $6m in Sano, a company developing a coin-sized glucose monitor that users would wear on their skin like a patch.

It is also working with bio-tech firm Dexcom on ways to let Fitbit users track their glucose levels on their smartwatches.

"We want to grow our business beyond wearables," Mr Park says.

"In five years from now, I want people to see us as a consumer electronics company but also as a digital health company that provides both devices and software to help people meet fitness goals or manage health conditions."