What next for Trump's trade agenda?

- Published

President Trump says new tariffs on steel and aluminium will help US workers

There's no doubt about the big question that looms now for international trade officials.

It is: what can they expect next from the United States under President Trump?

For decades after the Second World War, the US was arguably the biggest cheerleader for the gradual liberalisation of trade that took place.

Now, the US is the principal cause of anxiety among supporters of that process.

President Trump's approach to international commerce is assertive and confrontational, driven by an agenda described as economic nationalism.

It is a central element behind the escalating trade tension this week.

Some fear that this approach will undermine the system that has evolved in the last three quarters of a century.

Ambivalent

It is a complex system based to a large extent on rules managed through the World Trade Organization (WTO), supplemented with agreements among groups of countries that provide still deeper trade integration.

President Trump has shown little enthusiasm for those deeper agreements. He pulled the US out of one that had not been implemented as soon as he took office - the Trans-Pacific Partnership, and has threatened to repudiate another, the North American Free Trade Agreement.

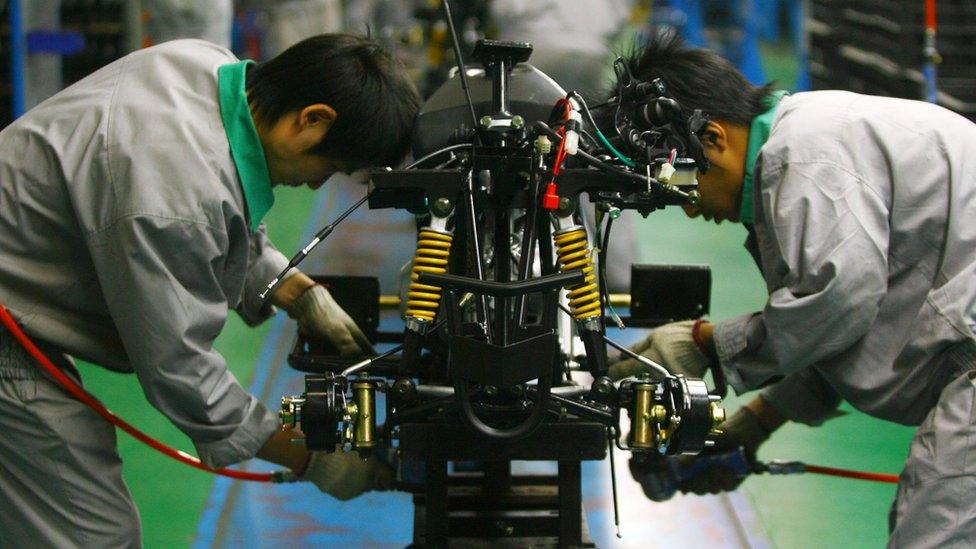

Motorcycles made in China are among the imports that could be hit with a US tax

On the WTO, the Trump administration has been ambivalent.

Some recent steps have been given a WTO justification. The controversial tariffs on steel and aluminium followed an investigation by the US Commerce Department which concluded that imports of the metals were a threat to national security.

In essence, the argument is that the US military needs a more reliable source of supply from the country's own industry.

WTO rules do permit countries to impose trade barriers to protect national security that would not otherwise be allowed.

It's another question whether national security really was the motivation and many critics, including the European Commission and China, don't believe it was.

Tariffs on imported washing machines and solar panels were safeguard measures, actions that are permitted in response to surges in imports, provided they are done in a way that is consistent with the WTO rulebook.

More difficult is the proposal, not yet implemented, to target Chinese goods with tariffs because of the country's alleged appropriation of the intellectual property - such as patents and designs - of American companies.

It is certainly true that protecting trade partners' intellectual property is required by WTO rules and the US concern about China is shared by others, including the EU, external.

The US has threatened to repudiate the North American Free Trade Agreement with Canada and Mexico

But countries are in most circumstances supposed to use WTO procedures before retaliating on the basis of a dispute panel authorising such action. The US has made an official complaint to the WTO but that only happened last week.

It will be many months until there is a ruling and even if China loses and fails to comply there will be a further delay before the US is given authority to retaliate. Will President Trump be willing to wait that long?

Unilateral action

So it is certainly possible that the US will jump the gun and decide to go ahead while the WTO process rumbles on. That would be hard to reconcile with the organisation's rules.

At a WTO meeting last week, external Chinese officials warned that unilateral action by the US undermines the multilateral trading system and sets a very bad precedent.

China's Ambassador Zhang Xiangchen, external told the meeting that member countries should act together to "lock this beast back into the cage of the WTO rules".

Still, the fact that the US has started the dispute settlement process can be seen as a sign that the Trump administration sees the WTO as useful.

It is worth noting that China is striking its first retaliatory blows without a WTO ruling, though there is a way that can sometimes be done under the rules. It is however debateable whether that provision really applies in this case.

The firing of US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson reflected a number of disagreements with President Trump, including the steel and aluminium tariffs

Still, the Trump Administration has a strikingly different tone on trade after its predecessor.

The economic nationalism that motivates President Trump and some of his team is disposed to see other countries as trading unfairly. It sees trade deficits as a sign of weakness, as an indication that trade agreements are defective and unfair.

It is true that President Trump has fired the most influential voice pressing this approach, his former chief strategist Steve Bannon. But the disagreements that led to that were not about trade.

And there are others of similar view still in key positions for trade policy. His Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross, the US Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer (who is in charge of negotiating trade deals) and the president's trade adviser, Peter Navarro, director of the National Trade Council are all from that mould.

Global Trade

More from the BBC's series taking an international perspective on trade:

Mr Bannon's departure did not reflect a disagreement over the economic nationalist agenda. But the resignation of Gary Cohn, as head of the National Economic Council did.

Mr Cohn was someone seen as resisting that agenda in the administration. The firing of Secretary of State Rex Tillerson reflected a number of disagreements with the President including the steel and aluminium tariffs.

One of President Trump's central views on trade is that other countries take advantage of the US. It is certainly true that US trade barriers are among the lowest. Tariffs - taxes applied to imports - are the easiest barrier to measure and average levels in the US are low. Not the lowest in the world as Mr Navarro has claimed, external.

Hong Kong doesn't have any at all and depending on how you calculate average tariffs several others are lower than the US. But certainly American tariffs are relatively low.

US trade barriers are relatively low, although some imports such as pick-up trucks carry high tariffs

There are some goods where American tariffs are high - known in the trade world as "tariff peaks". There are some in excess of 100% for agricultural products and there is a 25% duty on light trucks.

Does that mean other countries are taking advantage of the US? It's debateable. The mainstream view among trade economists is that the main losers from tariffs are buyers of the affected goods in the country that imposes them.

Main beneficiary

They have to pay more, either because they buy imports from a supplier that has to recover the cost of the tariffs or from a domestic supplier who is able to raise their prices as result of the protection afforded by the tariffs.

And sometimes the buyers of the affected goods are businesses that use them as inputs. Steel and aluminium are cases in point.

So there is a case that would be supported by many trade economists that the main beneficiary of low US tariffs is the US itself, particularly American consumers.

But President Trump's focus has been on producers - firms and employees - who see themselves as being hit by low cost, and they argue, unfair foreign competition especially from China.

- Published10 March 2018

- Published5 March 2018

- Published10 January 2018