Which country dominates the global arms trade?

- Published

US F-35 fighters on a training exercise in South Korea, 12 countries are due to operate the aircraft, including South Korea

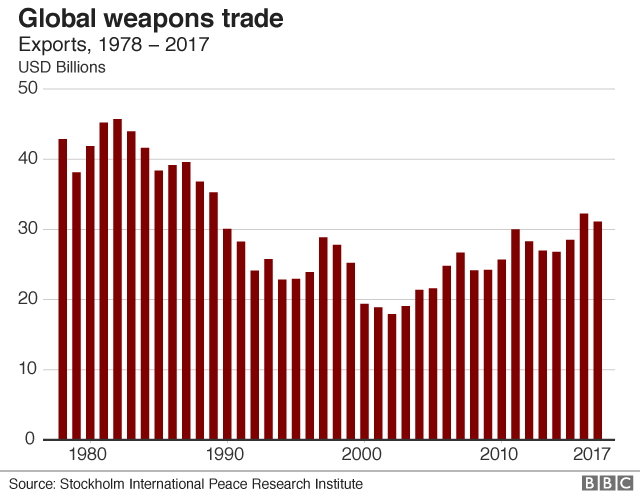

Brutal civil wars in Syria and Yemen, coupled with the return of great power rivalries between the US, Russia and China, have brought the world's arms trade into sharp focus.

And unsurprisingly it is a thriving global industry, with the total international trade in arms now worth about $100bn (£74bn) per year, Pieter Wezeman, senior researcher at the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (Sipri), tells the BBC.

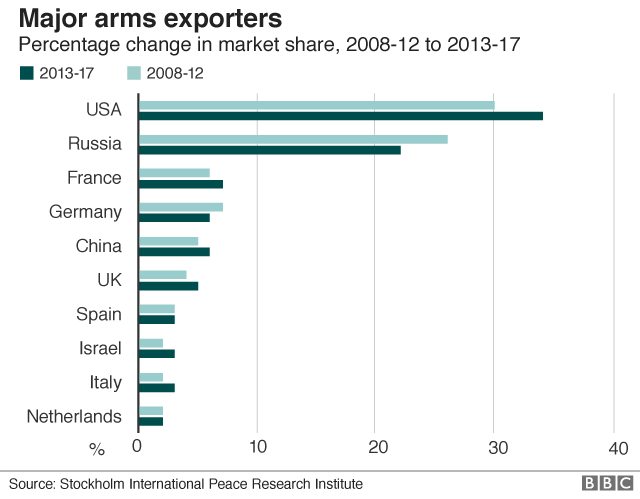

In its latest figures, the defence industry think tank says that major weapons sales in the five years to 2017 were 10% higher than in 2008-12., external

And it is the United States that is extending its lead as the globe's number one arms exporter, adds Sipri.

It estimates that the US now accounts for 34% of all global arms sales, up from 30% five years ago, and are now at their highest level since the late 1990s.

Saudi Arabia is now the world's top importer of US arms

"The US has been open to supplying arms to a large variety of recipients, and there are a large number of countries ready to acquire weapons from the US," says Mr Wezeman.

The US's arms exports are 58% higher than those of Russia, the world's second-largest exporter. And while US arms exports grew by 25% in 2013-17 compared with 2008-12, Russia's exports fell by 7.1% over the same period.

It is Middle East states that have been among the US's biggest customers - Saudi Arabia tops the list - with the region as a whole accounting for almost half of US arms exports during 2013-17.

Yemen's civil war

This comes as arms imports to the region have doubled over the past 10 years, driven by widespread conflicts across the area - most notably the civil wars in Syria and in Yemen, which the UN has called the world's worst man-made humanitarian disaster.

About 75% of Yemen's population are in need of humanitarian assistance

Since Yemen's civil war started in 2015, Saudi Arabia and eight other Arab states have carried out an air campaign in support of forces loyal to President Abdrabbuh Mansour Hadi.

These are fighting Houthi rebels said to be backed militarily by Iran.

The UN says that as of last November, at least 5,295 civilians had been killed and 8,873 wounded, external, although the actual figures are likely to be much higher.

The bitter conflict in Yemen has brought the ethical issues of international arms sales into sharp relief in many western countries, which have seen Saudi Arabia and its allies use their advanced weapons systems in the country.

"Saudi Arabia, Egypt and the United Arab Emirates were major arms importers anyway," says Sipri's Pieter Wezeman. "The major difference is that now they are using these weapons - in Yemen."

Saudi Arabia and eight other Arab states are carrying out air strikes to restore President Hadi's government

The UN says that Saudi-led coalition airstrikes continue to be the leading cause of child casualties as well as overall civilian casualties.

Meanwhile, rebel forces have fired artillery indiscriminately into cities such as Taizz and Aden, killing civilians, and also fired rockets into southern Saudi Arabia.

"There is a clear risk that arms sales contribute to human rights violations," says Oliver Feeley-Sprague, arms trade expert at Amnesty International.

"There are clear violations being committed by all sides. But in general, the more weapons get supplied, the more they risk being used."

The scale of the war in Yemen has led some countries to act: Norway, the Netherlands, Sweden and Germany among others, have all recently restricted arms sales to the region.

China's growth

Across in China, its economic rise has been mirrored by a growing defence budget and its increasing importance as a global arms supplier.

The country is now the world's fifth largest seller of arms. This puts it behind the US, Russia, France, and Germany, but ahead of the UK.

China is now the world's fifth-largest weapons exporter

China's arms exports rose by 38% between 2008-12 and 2013-17, and the country now has the world's second-largest defence budget after the US - $150bn compared to the latter's $602bn in 2017.

As China spends more on its defence industries, it means that it is it is also increasingly challenging the West when it comes to the technological sophistication of its weapons systems, external, says Meia Nouwens, research fellow at the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS).

"There should be no doubt that the PLA [People's Liberation Army] today is no longer far behind the West when it comes to certain areas of defence technology," she says. "The West's superiority in the air is under growing threat.

"China may not yet be able to produce high-performance military jet engines, but with the rate they are innovating they are not light-years away from being able to do it."

China's first aircraft carrier, the Liaoning: China is said to be planning to have four carrier battle groups

China's increased military spending comes as it is moving from being a land-based military to becoming a naval-based power - and has poured huge sums into its growing navy.

Since 2000 it has built more warships than Japan, South Korea and India combined - the total tonnage of new warships and auxiliaries launched in the last four years is greater than that of the French navy. Other countries across, such as Japan and India have responded by spending more on naval power.

Asian military spending: Japan's latest helicopter carrier Izumo, though officially a "destroyer", is its biggest warship since World War Two

"China has grown at a staggering rate, economically, and is seeking to transform that into a military power that is consistent with a regional hegemonic position," says Veerle Nouwens, research analyst at Royal United Services Institute (Rusi).

Part of this strategy includes China's efforts to export its arms. It sold weapons to 48 countries during 2013-17, with Pakistan being its top customer, and it is making inroads into some of Russia's traditional export markets.

India is also spending more; its defence imports rose 24% between 2008-12 and 2013-17 and is building six of these French-Spanish designed submarines

"They are both selling to similar customers - countries that the west won't sell arms to - like Iran, Venezuela, Sudan and Zimbabwe," says Dr Lucie Beraud-Sudreau of the IISS.

African conflicts

In a world where arms sales are rising, the major exception to this seems to have been Africa. Between 2008-12 and 2013-17 arms imports by African countries fell by 22%.

Yet crucially, the figures here do not tell the whole story. Internationally, arms sales are measured by the total value of the contract - but this downplays the significance of small arms and light weapons to continuing conflicts in Africa, most notably South Sudan's civil war.

"We are not seeing significant reductions in the fighting in South Sudan, and this is clearly being fuelled by significant purchases of small arms and light weapons," says Amnesty International's Oliver Feeley-Sprague.

"For instance, three shiploads of machine guns, which would make a huge difference to armed groups on the ground, yet would not even show up in the statistics."

In 2014 the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT) came into force, with the aim of regulating the international trade in conventional weapons.

It requires states to monitor arms exports, and ensure that their weapons sale don't break existing arms embargoes, or end up being used for human-rights abuses, including terrorism. Yet so far its impact has been limited, say critics, external.

"We are disappointed by the way a number of states have decided to implement it, says Amnesty's Oliver Feeley-Sprague.

"We think the UK, US and France among others, by continuing to sell arms to Saudi Arabia and its allies in the coalition operation in Yemen, are clearly violating the ATT's provisions."

About a third of South Sudan's population has been displaced by the conflict, which broke out in December 2013

Last July, the UK's High Court ruled that the UK government's arms sales to Saudi Arabia are lawful.

However, the Campaign Against the Arms Trade (CAAT) has been given permission to appeal against this ruling, and the case will now go to the Court of Appeal.

The UK government says it has "one of the most robust export control regimes in the world".

The ATT may have had a bigger impact on curbing the flow of weapons to non-state actors, says Sipri's Pieter Wezeman - but so far it has not had any visible impact on the overall trade in arms.