The truth about Tulip Mania

- Published

In the 17th Century the Dutch went mad trading tulip bulbs in the hope they could make a massive profit. But was Tulip Mania - a parable of greed compared to the recent heavy investment in the Bitcoin crypto-currency - really so awful?

How much is a thing worth? An ounce of gold? A kilogram of apples? A share in Apple?

One simple way of answering that question is to say that it's worth whatever its price may be in a financial market.

But sometimes prices go too high and inflate what is called a speculative bubble.

The fictional financier, Gordon Gekko, in the movie Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps, described "the greatest bubble story of all time".

"Back in the 1600s the Dutch got speculation fever to the point that you could buy a beautiful house on the canal in Amsterdam for the price of one bulb," he said.

"Then it collapsed," he added. "People got wiped out."

The enduring power of so-called Tulip Mania means it still gets trotted out in 2018 when people talk about Bitcoin, which reached a record high last November, but has since fluctuated in value., external Those who are sceptical of the digital currency feel that the dizzying rise in the price of something with no intrinsic value, external has all the hallmarks of the tulip bubble.

But modern research suggests we've misunderstood the tulip trade. It wasn't speculative fever but cultural factors that made people value the flower.

"After you grow a white tulip for nine years or so, suddenly it will become striped or speckled," says Anne Goldgar, professor of early-modern European history at King's College London. "This is because of a disease, but people were not aware of that at the time.

"You didn't really know what was going to happen with your tulips and people loved the fact that they constantly were changing."

In the 17th Century tulips - originally cultivated in the Ottoman Empire - were a new arrival in the Netherlands and their changing colours made them a hot product for the aesthetically attuned.

The tulip trade became an object of satire among 17th-Century artists

Wealthy Dutch people were keen to show off their high-class taste.

"There were a lot of people who had money to spend," says Prof Goldgar. "The same people who bought paintings tended to be the people who bought tulips."

Prof Goldgar says that while some flowers saw prices as high as 5,000 guilders - the cost of a nice house - these were very rare. "I found only 37 people who spent more than 400 guilders on flowers at any point at that time."

Four-hundred guilders might not buy a house, but that was still more than the yearly salary of an unskilled labourer.

'Canal drownings'

Tulips saw a massive increase in prices at the end of 1636, lasting until they plummeted on 6 and 7 February 1637.

Prof Goldgar says the crash was probably caused by unsustainability, and fears of oversupply. But the effect wasn't nearly as bad as the story suggests.

"I looked to try and find anybody that was made bankrupt, because this is the myth of course that people were drowning themselves in canals because they were made bankrupt," she says. "Actually I couldn't find anybody that was bankrupt because of Tulip Mania."

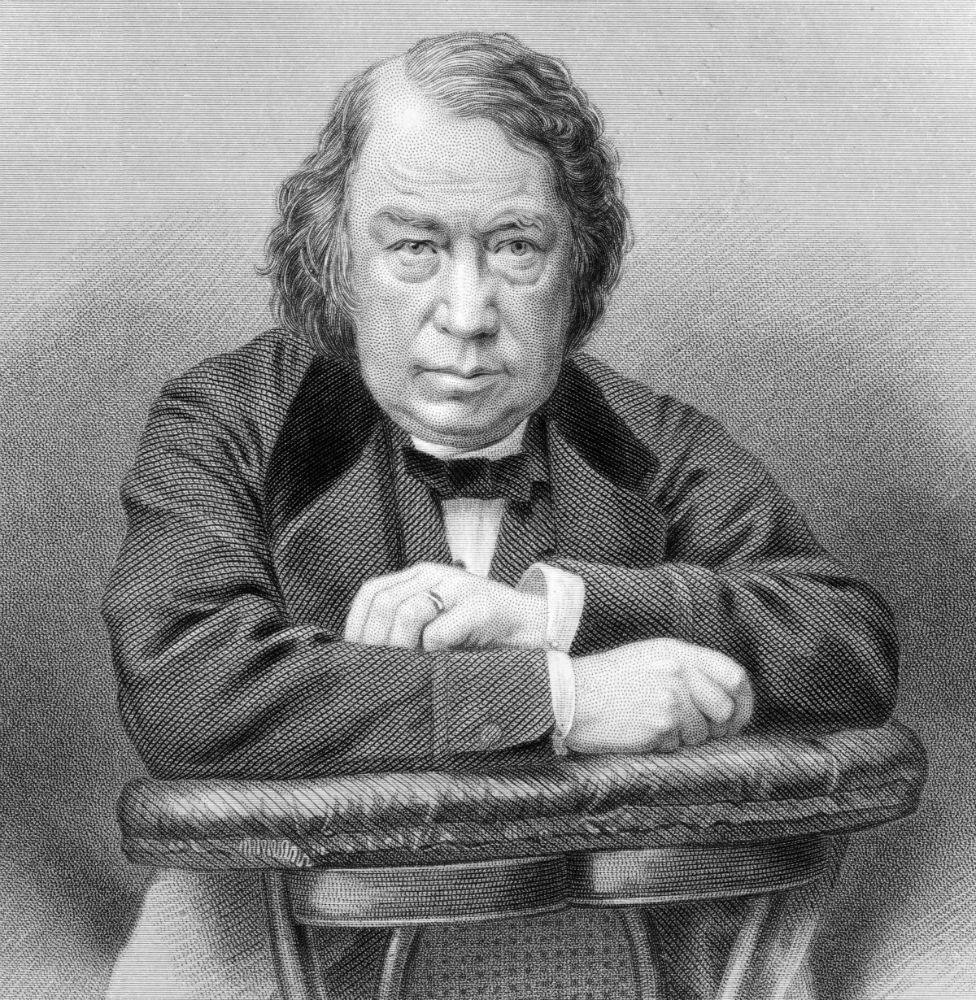

Is Charles Mackay to blame for the mythology surrounding Tulip Mania?

No one drowned themselves in the canals. But that doesn't mean the bursting of the tulip bubble didn't cause some issues.

"Bulbs stay in the ground for almost the entire year and so the only time you can exchange the bulbs is between late May and August when you can dig them up," says Prof Goldgar.

"The problem was that the rest of the time people were buying bulbs that they didn't receive until June - and they didn't pay for them until then either. So there were lots of people during the period of the crash who bought them but never paid for them."

But overall, Prof Goldgar says, the Dutch economy was not affected.

Railway bubble

So why is the speculative story so well known?

Tulip Mania was popularised by an account written by the 19th-Century Scottish writer Charles Mackay, who loved a juicy story. He's not taken seriously as a historian, but his vivid tales have caught on.

Ironically, Mackay himself was caught up in a bone-fide financial mania: the British railway bubble of the 1840s, which some scholars regard as the biggest technology bubble in history, followed by one of the biggest financial crashes.

That, surely, is a lesson for us all: it's very easy to scoff at past bubbles, and even to exaggerate the stupidity of those caught up in them.

But it is not so easy to know how to react when one may - or may not - be involved in one.

More or Less is broadcast on BBC World Service at 19:50 GMT on Sunday 13 May. It will also be available on BBC iPlayer and here.