Hidden writing in ancient desert monastery manuscripts

- Published

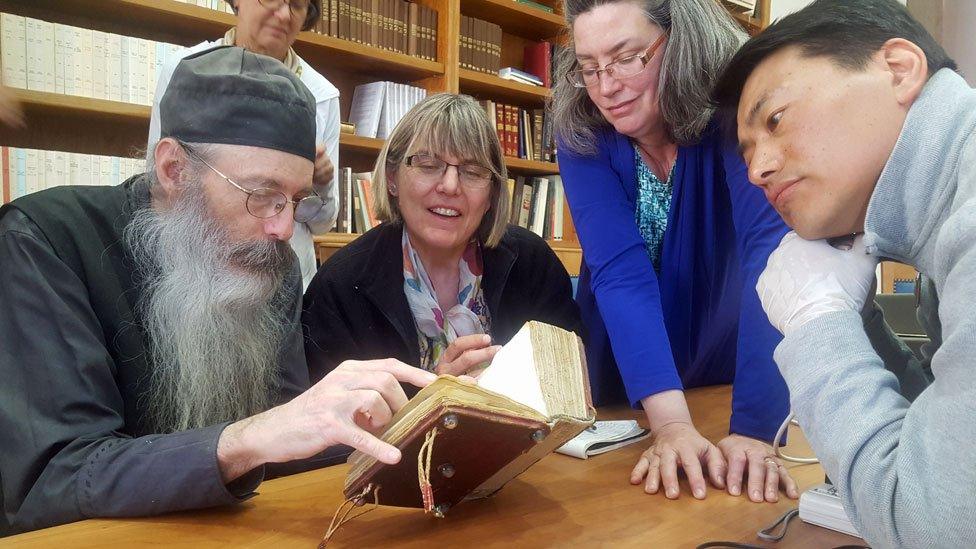

Fr Justin is helping to share online the historic manuscripts in an ancient Sinai monastery

For a monk who lives in the Sinai desert in Egypt, in the world's oldest working monastery, Father Justin replies to emails very speedily.

It should come as no surprise: the Greek Orthodox monk is in charge of hauling the library at St Catherine's into the 21st Century.

This ancient collection of liturgical texts, including some of the earliest Christian writing and second in size only to the Vatican, is going to be made available online for scholars all over the world.

The manuscripts, kept in a newly-renovated building which was opened to the public in December 2017, are now the subject of hi-tech academic detective work.

East meeting West

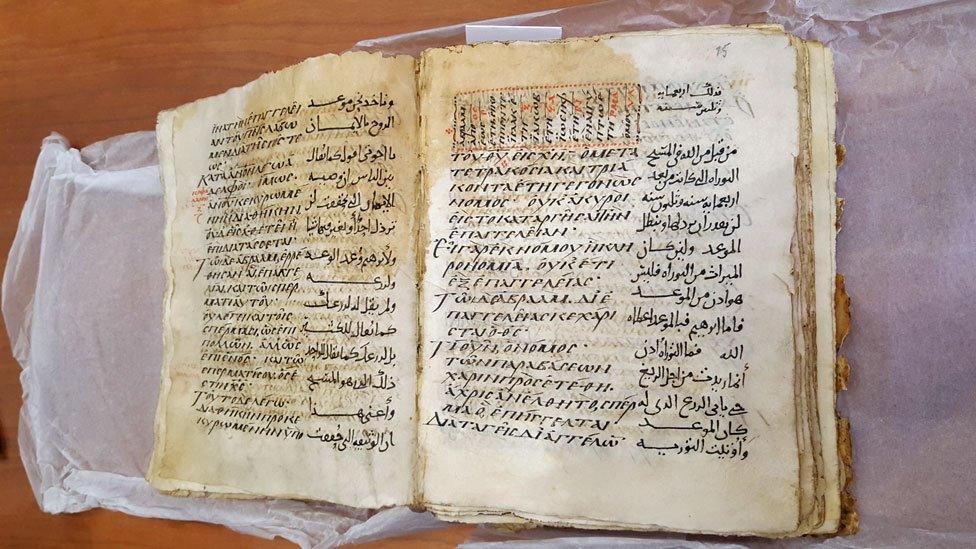

A team of scientists and photographers working alongside Fr Justin has been using multi-spectral imaging to reveal passages hidden beneath the manuscripts' visible text.

These include early medical guides, obscure ancient languages, and illuminating biblical revisions.

Among the researchers is Michelle P Brown, professor emerita of medieval manuscript studies at the University of London.

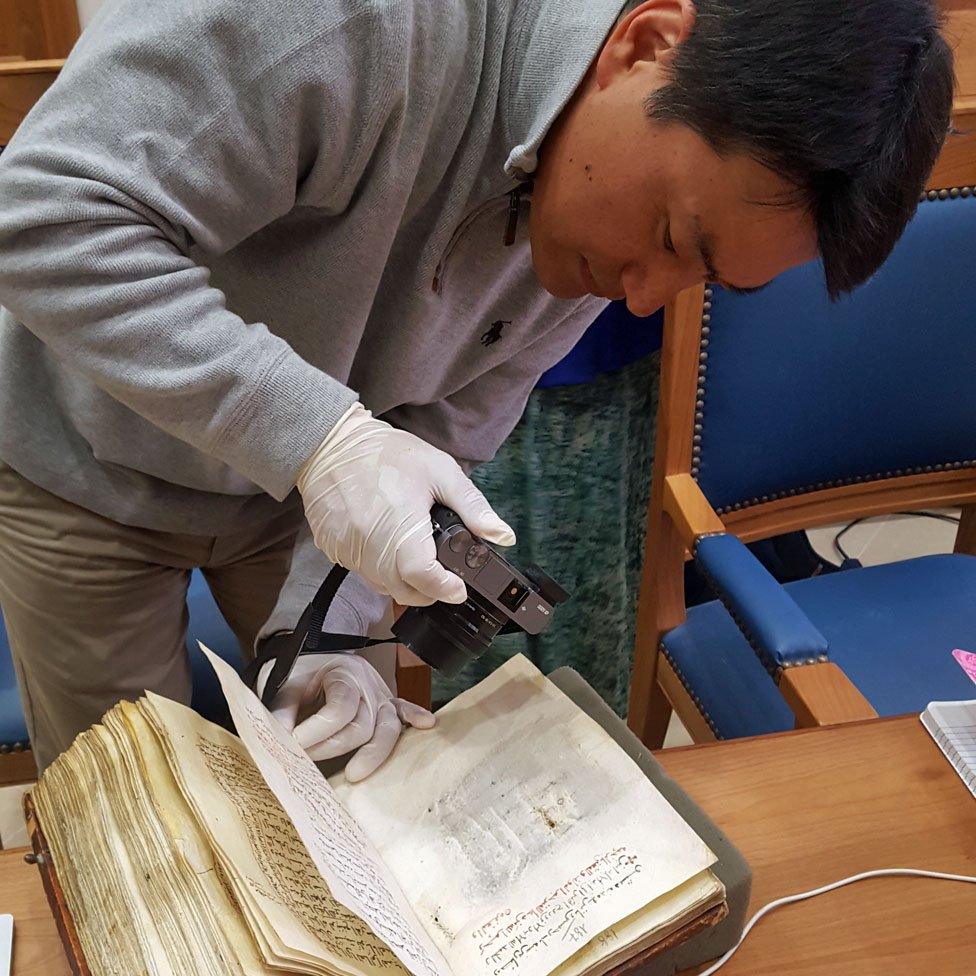

The monastery is scanning manuscripts for writing hidden below the surface

She was convinced from earlier visits that she could challenge the mainstream thinking that there had been little face-to-face contact between the far West and the Middle East between the 5th Century and the crusades in the 12th.

The oldest known copy of the gospels in Arabic - or rather what lay beneath it - proved her right.

At least 170 of the 4,500 manuscripts in the collection are recycled manuscripts, known as palimpsests.

Industrious monks often had to resort to scrubbing the ink off neglected tomes before reusing the parchment.

Although the manuscript examined by Prof Brown had been discovered in 1975, it is only now that scholars have been able to distinguish the different layers using a variety of light waves. Before they relied on the naked eye or corrosive chemicals.

Computer analysis of pages

Now, each page is photographed 33 times using 12 different wavelengths. The images are analysed using computer algorithms, and several images are combined to make the undertext more legible.

If this doesn't yield results, the page is analysed using statistics: each pixel is assigned a value, separated into categories, then manipulated according to those categories to make that selection more visible to the human eye.

Scholars have been coming to the monastery's unique collection for centuries

The techniques mastered in Sinai have been used by EMEL, the Early Manuscripts Electronic Library, which is based in California, on collections belonging to Cambridge University and the Berlin State Library as well as the faded diaries of explorer David Livingstone written on his trips to central Africa.

As chief camera operator on the Sinai Palimpsest Project, Damian Kasotakis visited the monastery four to five times a year, for two to six weeks, over a period of five years. There were challenges, repairing such complicated technology in the desert proved difficult.

They had to "follow the monastic spirit of the place" and Fr Justin's schedule, breaking for lunch and Vespers.

"It's a place where you can either stay and feel freedom or feel like the huge mountains will fall on top of you," he says, eager to return.

Greeks and Saxons

The team processed 6,800 pages, Mr Kasotakis estimates, which took on average eight minutes each. This is a small proportion of the library's collection. He remembers Prof Brown's manuscript with "weird shapes that looked like flowers."

It turned out that part of the gospels had been made from an ancient Greek medical text which advised treating scorpion bites with a paste made out of a plant boiled in olive oil.

St Catherine's is claimed as the world's oldest working monastery

The rest of the manuscript sheds a light on international relations during the dark ages and an "incredibly complex interaction of different cultures," says Prof Brown.

The palimpsest revealed traces of Greek writing from the 5th or 6th Century, then Latin a century or so later, perhaps by hands trained in Rome and Sinai, then traces of two Anglo-Saxon scribes, before it was eventually used for the Arabic writing.

The presence of Anglo-Saxon scholars in Sinai lends credence to Prof Brown's hypothesis that Celtic sites like Skellig Michael, far off the west coast of Ireland, show evidence of the influence of Eastern monasticism.

There has been a long tradition of scholars coming to Sinai and trying to look below the surface of the monastery's manuscripts.

Women saints

In the 1890s, Margaret and Agnes Lewis, twins from Scotland, discovered a palimpsest after travelling nine days through the desert on camel to Sinai. The twins, despite mastering 12 languages between them, had been infamous in Cambridge until then mostly for exercising in their backyard in their bloomers.

The top layer of the manuscript was devoted to the lives of women saints.

The library is being digitally captured so that scholars can examine manuscripts online

Using a chemical re-agent which had never been tested, they revealed what came to be known as the Syriac Sinaiticus, the oldest known copy of the gospels in Syriac, a dialect of Aramaic, which dated from the late 4th Century.

Terror attacks

Sinai has always been a place where different cultures collide, perhaps now more so than ever.

"A lot of people are hesitant to come here because of what they read in the news," admits Fr Justin.

There have been terrorist attacks on Coptic Christians in the north of the peninsula.

In April 2017, an army officer was killed by a gunman at the checkpoint leading up to the monastery. There are now two checkpoints between the village and the monastery. Snipers hide in the hills like hermits and floodlights light up the cragged mountains at night.

There are checkpoints, barriers and snipers guarding the way to the monastery

Yosoeb Song, a pastor studying at the Lutheran School of Theology of Chicago, had until a few years ago depended on poor-quality black-and-white microfilm to analyse an Arabic manuscript held at the monastery.

In 2016, Fr Justin sent him 269 high-resolution images. It was the first time he'd seen the red ink of the rubrics and sections that scribes had erased and written over, including the name of the person to whom the 8th-Century text had been dedicated.

It was then he decided to come to Sinai and see the manuscript and what looked like medieval correction fluid in person.

It is a "unique place," says Mr Song, and one of the only monasteries with a mosque within its walls. The pastor wants to use his research to "overcome misunderstandings", particularly in Korea where the Muslim population is growing.

Muslim protection

In 625AD, Mohammed signed a charter "in aid of the Christians" with a gold handprint. A copy of this, guaranteeing the monastery's protection, hangs in the museum.

The Jebelaya tribe, local Bedouins, who have helped protect and run the monastery since it was built, are Muslim.

The monastery has had to survive centuries of political upheavals in the Middle East

If any visitors complain about Muslim prayers within the walls, Fr Justin is quick to correct them: "This is Sinai. We have collaboration and mutual respect."

Hemeid Sobhy, who has been his assistant for the last 12 years, was the first member of the Jebelaya to attend a public university. Unable to find a job in finance, he returned to the monastery where his father and grandfather had both worked.

Fr Justin is focusing on photographing the Arabic and Syriac manuscripts first to "reaffirm the Arabic-language heritage we have". The EMEL team are returning to photograph these manuscripts so they are available online.

But with the political climate in Egypt, Fr Justin says, it has become more difficult for Greeks, and by extension Christians, to stay in the country and easier for them to leave.

"We are not foreigners that can be evicted. We are an essential part of Egypt's long history and we have to stress that."

More from Global education

The editor of Global education is sean.coughlan@bbc.co.uk