Ocado delivers for 'patient' investors

- Published

Food delivery tech firm Ocado has had a good week

There may be a wry smile on the faces of Ocado's founders and investors this weekend as they reflect on a remarkable few days.

Once a perennial disappointment with their jam-tomorrow promises, the directors have taken the online food retailer from zero to hero.

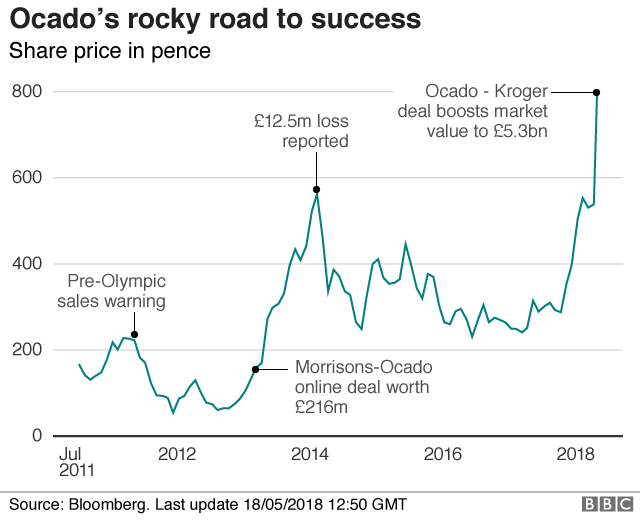

Thursday's announcement of a deal with US retail giant Kroger sent the share price soaring as much as 80%, as the value of Ocado rose billions of pounds and it overtook Marks & Spencer in stock market size.

Suddenly, Ocado was being talked about as not just an online retailer, but a cutting-edge technology company that could help supermarkets fend off Amazon's move onto their turf.

Co-founder and 3.8% shareholder Tim Steiner has not enjoyed such headlines since he started the company 18 years ago.

And retail veteran Lord Rose of Monewden certainly joined a winner after stepping down as chairman of Marks & Spencer and taking a similar post at Ocado in 2013. He has more than one million shares.

Last week's deal will see Ocado share with Kroger its technology that automates online grocery orders under an exclusive contract.

The UK company is known for the robotic tech in its warehouses to process and pack food orders, and will build similar factories for Kroger. Analyst Bruno Monteyne says the number of sites - or what Ocado calls customer fulfilment centres (CFCs) - being built will far exceed expectations.

Ocado's distribution centres have embraced AI and machine learning alongside its human staff

He says there were rumours of a Kroger deal ahead of the official news. But the announcement was bigger than anyone forecast, hence the share price surge. "We envisaged one CFC to start. This deal is materially larger for up to 20 CFCs," he said.

It's the fourth such international agreement Ocado has reached in six months, but the biggest so far given the size and potential of the US retail market.

Says Laith Khalaf, senior analyst at Hargreaves Lansdown: "The threat of a big disruptor [Amazon] entering the sector puts pressure on food retailers to be on top of their game when it comes to online deliveries, and that's where Ocado comes into its own."

It seemed so different just a few years ago. "Ocado is a business that delivers a good service for customers but not for shareholders," said Shore Capital analyst Clive Black in 2012.

Patient investors

It was a year in which Ocado's finances were so wobbly that there was speculation about it breaching bank lending covenants, and the share price stood at about 60p - against Friday's close of 800p.

Even recently investors were betting that the share price would fall, a process called 'shorting' a stock.

Says Mr Khalaf: "As one of the most shorted stocks in the UK stock market [the Kroger] deal will be a poke in the eye for the hedge funds who have bet against Ocado.

"The short sellers were hoping Ocado wouldn't deliver on its international expansion plans. That position now looks like a badly busted flush."

Turning point

Retail Economics chief executive Richard Lim said the patience showed by early backers and Mr Steiner was now being rewarded as the company was showing it could scale up and ink contracts with major retailers internationally.

"The investment in automation, data and AI and the overall patience has paid off. It has been the foundation of Ocado's success," Mr Lim said.

The retail analyst predicted success would come to Ocado much as it had in the past 12 months, through exclusive contracts to build tech-heavy distribution warehouses for leading retailers.

"Ocado is really at the heart of the tech wave that is disrupting the retail sector. They are leaps ahead of the tech offerings that many retailers offer," Mr Lim said.

No basket case

The company was set up in 2000 by three former Goldman Sachs investment bankers - Mr Steiner, and colleagues Jonathan Faiman and Jason Gissing.

Ocado's launch was helped by Waitrose, which injected £46m to help it build a distribution base in Hertfordshire and gave the operation an upmarket polish.

In return, Waitrose supplied Ocado and took a 40% stake in the fledgling business.

But Ocado never shook off suspicion that it would struggle to succeed. When the company listed its shares on the London stock market in 2010 - a flotation that went through only after it cut the share offer price - Ocado had still not made a profit.

For a long time there were questions about how the tech company could expand its business because of contractual ties to Waitrose.

It eventually signed a £216m deal with Morrisons in 2013 to operate a new online grocery service for the supermarket group. That at least gave investors comfort that there was life beyond Waitrose, a relative small fish in the UK's grocery pond.

Ocado co-founder Tim Steiner, seen here with partner Patrycja Pyka, is the only co-founder to still be with the company

In 2016 Mr Steiner, aware of Amazon's desire to move further into grocery delivery, spoke of the company's strategy to expand the "Ocado smart platform", which was all of the technology and infrastructure behind the website, and partner with well-established retailers in Europe.

The strategy paid off with recent deals announced with France's Casino supermarket chain and Swedish grocer ICA.

As of 2018, Mr Steiner is the only member of the founding trio to remain at Ocado, where he is chief executive.

Mr Gissing retired in 2014, while Mr Faiman departed in 2009 and has since entered the oil industry by investing in and becoming chairman of exploration group Neos.

Mr Steiner once said that far too much time in business is spent worrying about historic decisions. Maybe that's why he has stuck at it, and is now enjoying a few plaudits after 18 years of hard graft.

- Published17 May 2018

- Published9 May 2018

- Published4 February 2018