Could a text message save thousands of fishermen's lives?

- Published

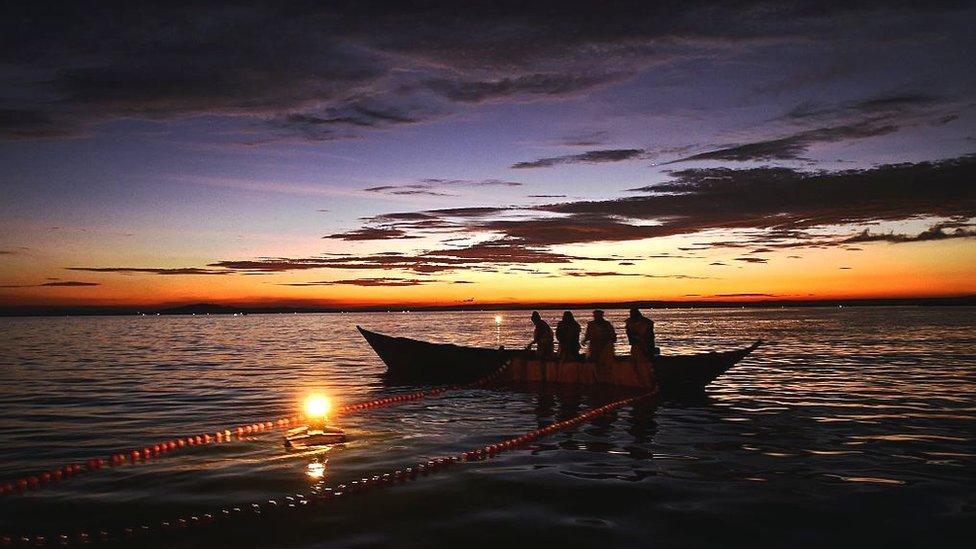

Much of the fishing takes place at night when lethal storms can blow up quickly

We can't stop nature when it unleashes its fury in the form of volcanoes, earthquakes, storms and avalanches, but we can use technology to warn us of imminent danger - and save lives.

As the sun sets over Lake Victoria, Africa's largest lake, tens of thousands of fishermen ready themselves to head out on the water for the night, fishing mostly for tilapia and Nile perch.

As they push off, they know they are risking their lives - some of them may never be seen again.

Lake Victoria - a lake so big it straddles Uganda, Tanzania and Kenya - is notorious for its deadly storms. At this time of year, strong winds, rain, lightning and huge waves are a regular occurrence.

Up to 5,000 fishermen lose their lives each year, says the International Red Cross.

"The storms usually start at midnight and last until around 6am," says Amone Ponsiano, officer in charge at the Marine Police, Nkose Island, Uganda.

"This is the exact time when the fishermen are very busy, collecting their nets. It's very dangerous and we have a lot of people disappearing."

Marine policeman Amone Ponsiano says lots of fishermen disappear during storms

Recently, one man's boat was smashed on the rocks as he tried to escape a violent storm, but Mr Ponsiano's team managed to fish him out of the water in the nick of time.

But a new early warning system developed by an international team of scientists and technologists could end up saving hundreds of lives.

Simply put, real-time satellite data from Nasa is applied to a statistical model and used to forecast the probability of an extreme thunderstorm. This probability is translated into a simple warning message delivered to fishermen via text message, Twitter or WhatsApp.

Prof Wim Thiery, lead researcher on the project - a joint venture between Brussels-based university Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Switzerland's ETH Zurich university, Nasa, and CodeForAfrica - says there is a "great potential" for new technologies, in particular machine learning, to improve the prediction of extreme weather.

Storms over Lake Victoria can be violent and deadly

As erratic weather becomes more common due to climate change, such tech will become increasingly important to make us "less vulnerable", he says.

"Just like with the traditional weather forecast, there will always be misses and false alarms," he admits. "We are dealing with a deterministic chaos system, so you can't predict everything.

"But we clearly see that with time, our ability to forecast extreme events improves, thanks to better weather models, better supercomputers, and innovative techniques."

Extreme weather isn't only a mortal peril in Africa.

In 2014, Stanford engineering student Ahmad Wani found himself marooned for a week awaiting rescue from extreme flooding in Kashmir, India. The floods claimed hundreds of lives.

Since the incident, he has focused his engineering skills on developing a machine learning platform aimed at predicting the impact of natural disasters. Better predictions would enable urban communities to prepare better, he believes.

Floods in northern India take scores of lives and cause huge damage to infrastructure

Teaming up with two of his student colleagues, Mr Wani co-founded One Concern to tackle the issue.

"By 2030, 60% of the world's population will live in cities," he says, "with 1.4 billion facing the highest risk of exposure to a natural disaster.

"These are sobering statistics, but the good news is outcomes can be changed. By having the insights to better prepare for, respond to, recover from and mitigate against disasters, leaders can reduce the risk that their people face," argues Mr Wani.

Analysing huge amounts of data and developing predictive models has helped them advise communities on how to improve their disaster response plans.

For example, one client had stored supplies for shelter, water, and first aid in a community-owned building they had planned to use as a shelter and relief staging point in the event of an earthquake.

But One Concern's simulations showed that this building stood a high chance of being significantly damaged, so was unsuitable for the role.

The emergency response plan needed rethinking; the building needed strengthening.

The company is currently working with Los Angeles and San Francisco on how to disaster-proof their cities, and aims to roll out its platform globally.

"We are on a mission to save lives and livelihoods and believe in the power of benevolent artificial intelligence to help do so," Mr Wani says.

Colorado-based Avalanche Lab believes that even simple tech can save lives.

This road in Tajikistan was hit by 40 avalanches in January 2017, killing eight people

About 150 people are killed by avalanches every year. But with two thirds of the world's population owning a mobile, half of which are smartphones, Avalanche Lab thinks a phone app could prove the most effective avalanche prevention and rescue tool in the winter survival kit.

The AvyLab "crowdmaps" avalanche data and makes it accessible to those out in the snow. Users record snow observations, pin notes on a map, and share the data with the community. Meteorological information is also provided via the app, with the aim of helping users make informed decisions about venturing out.

"A phone app for avalanche safety is not a 'magic bullet' for decreasing avalanche incidents," says AvyLab app creator Michael Murphy, "but rather a way for creating a more informed and connected general public, which will make a difference in decreasing avalanche fatalities."

More Technology of Business

Tech to warn of impending disaster is being applied around the world to save lives, limit infrastructure damage and aid emergency services.

In Mexico, for example, start-up Grillo is installing $50 (£37) seismic sensors along the coast to give early warning of impending earthquakes to residents via a smartphone app. Such warnings may only give residents an extra 90 seconds to prepare, but that's enough potentially to save lives, the founders believe.

Tech may not be able to control Mother Nature, but at least it is helping us prepare for an unpredictable world.

Follow Technology of Business editor Matthew Wall on Twitter, external and Facebook, external